Trying to Look the Part

– Sugar?

– No, thanks.

A pause. The air thick with awkwardness. His gaze steady, he says, “men don’t like humble women, you know.”

My mother, my sister and I bumped into him a minute ago. He’s the ex-husband of one of my mother’s dear friends. Despite our excuses to save ourselves a chat over tea and coffee at his home, here we are.

I feel like retorting, “If by men you mean men like you, I’ll pass on the advice” or “I don’t see how liking one’s tea unsweetened has anything to do with humility.” Like many girls though, I was raised to show a certain deference to male authority figures. So, I hold back my irritation. Still, I decline the sugar. And the milk. My stubbornness a form of quiet rebellion.

Looking back, I understand both why I felt anger and why I kept it in. Society conveys the idea that it’s inappropriate for girls and women1 to get angry: “girls learn to be deferential, and anger is incompatible with deference,” as Soraya Chemaly says in her TED talk “The Power of Women’s Anger.” That anger is “the moral property of boys and men” has a disastrous impact: “severing anger from femininity means we sever girls and women from the emotion that best protects us from injustice.” Girls grow to disdain anger rather than welcome this emotion in themselves, and we penalize them for expressing it instead of encouraging them to voice their anger in the face of injustice.2

Not that the anecdote above illustrates an injustice. Yet a remark, however well-meaning, can be symptomatic of a bunch of things that aren’t right in our world: the implicit demand that girls and women be sweet all the time and that they adjust their behaviors to boys’ and men’s liking, the unwritten rules as to what qualities girls and women must embody and what faults they are allowed to have, our noes not being taken seriously (say yes to the invitation, smile, give in).

As women, we are expected to perform roles assigned to us at birth. We are on display when we move in public and we develop a hyperawareness of how we present ourselves, which Roxane Gay explores in her essay “Garish, Glorious Spectacles” in which she examines Kate Zambreno’s Green Girl3 and dehumanizing reality tv shows. (BF, p. 81)

In order to be regarded as successful, women had better show no chink in the armor. This quote attributed to Leslie M. McIntyre that I found in Julia Cameron’s The Artist’s Way encapsulates this idea: “Nobody objects to a woman being a good writer or sculptor or geneticist if at the same time she manages to be a good wife, good mother, good looking, good tempered, well-groomed and unaggressive.”

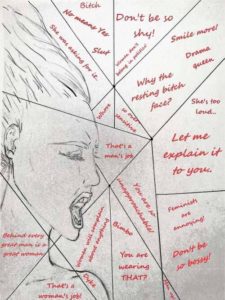

“Out of Line” by Kristina Stoyanova

Strangers Teaching Lessons

When we don’t conform to societal expectations, men in particular teach us a lesson. Sometimes the reproach is seemingly mild enough. For instance, we get offered unsolicited advice. In her essay “Men Explain Things to Me”, Rebecca Solnit discusses what became known as the phenomenon of “mansplaining” which refers to a man condescending to a woman by explaining things she knows more about than he does (please have a look at Nicole Tersigni’s funny and relatable Men to Avoid in Art and Life).

Strangers telling women to smile is another example of everyday sexism. It seems that, whatever women do, they’re bound to feel trapped. If you don’t smile, you prevent men from mistaking your friendliness for flirtation, but you lay yourself open to them ordering you to cheer up. If you do smile and act charming, you protect yourself against one form of street harassment, but you might risk another (unwanted touching, whistles, and the like). Women shouldn’t put themselves under such ridiculous pressure and almost ask for permission to sulk in public. Why not simply let a woman be and feel her feelings rather than mind her facial expressions? Why not accept the fact that just because she’s not smiling right here and now doesn’t mean she’s angry? In Glennon Doyle’s words, “Why does a woman’s neutral face mean anger, while a man’s neutral face means neutral?”

It’s crucial not to shrug off instances of everyday sexism and sneaky misogyny for, although common, they reveal a “violent cultural sickness – one where women exist to satisfy the whims of men, one where a woman’s worth is consistently diminished or entirely ignored,” as Roxane Gay puts it. (BF, p. 189)

Other times the punitive action is physically violent.

I once saw “here I was harassed” written near calm water. The sky-blue words were neat. The person used a stencil to color the letters, perhaps seeking to warn others without making waves. It was anything but hasty, showy, or aggressive. I expected to find a feel-good message. That one would choose to make a powerful statement by making such understated choices took me aback somehow. This made me think of how we need to get taken aback more often in our culture – so that we can revolt, so that we can fix what’s broken in our system – i.a. when it comes to rape.

We are inundated by rape imagery and representations of sexual violence and “by the idea that male aggression and violence toward women is acceptable and often inevitable.” (BF, p. 129) This permissiveness toward sexual violence (BF, p. 133) desensitizes us to the shock of it, causing cultural numbness. Gay suggests a rewriting that doesn’t make violence exploitative and restores the actual brutality to sexual offences. (BF, pp. 135-136)

The feeling of unsafety doesn’t appear to go away over time. I once met a woman in her seventies at the railway station. She told me that, one day in the early hours, she drove her son to the airport. Not to get assaulted, she parked her car amid trucks and made her way through the parking lot with her dog, disguised as a man. This camouflage trick – her playing the role of a man – helped her ensure a feeling of security.

How Pathologizing the Unlikable Is Harmful

Coming back to the discussion on whether or not being approachable – in the street or elsewhere – can protect women, I’d like to touch on likability. In both reality and fiction, social conformity for women entails playing likable characters. In “Not Here to Make Friends”, Roxane Gay defines likability as “a performance, a code of conduct dictating the proper way to be,” and denounces our “cultural malaise with […] all things that dare to breach the norm of social acceptability.” (BF, p. 85) She then discusses how critics tend to diagnose female characters with mental illness when they question their likability, “[p]athologizing the unlikable in fictional characters.” (BF, p. 91)

In real life, the reckless use of labels such as drama queen or psychotic girlfriend to refer to women whose behavior deviates from social norms is hurtful, too. The association between unlikability and mental struggles reinforces the stigma around mental illness, and implies that to be mentally ill is to be unlikable. We need more so-called unlikable women on-screen so that, off-screen, we can feel greater compassion for ourselves and others.

Gender Development & Compassion

Now, it’s important to avoid gender polarization. It doesn’t make sense to try to achieve gender equality by encouraging men and women to fight one another.

It’s a commonplace that women are more emotional than men. Two main reasons seem to account for it, as Martha Nussbaum observes in Upheavals of Thought:

- In many societies, moral education encourages girls to value “personal relationships of love and care that are the basis for most of the other emotions,” while encouraging boys to seek separateness from their mothers and later from others;

- “the lives of women in many parts of the world are socially and materially shaped so that, with respect to the very same external goods, they have less control and greater helplessness.”4

Yet brain-imaging studies confirm that men’s and women’s brains are near-identical, thereby challenging neurosexism and debunking the myth of a gendered brain. “[The] scans revealed that only 0.1 percent of the male population is stereotypically male or female. […] —essentially all of us—are a combination of male and female characteristics.” If one considers compassion in particular, both genders have an equally strong need for connection and belonging.5

Scientists found that compassion is innate and instinctual, but various probable factors explain why men and women may indeed differ in how they experience and express compassion. Our evolutionary needs appear to have determined the ways we respond to stress. That men tend to handle stress with “fight or flight” responses, while women usu. “tend and befriend”, may be due to ancestral tendencies: women would express their compassion through nurturance and bonding, while men would express this emotion “through protecting and ensuring survival.” Another factor is socialization: through a different socialization process, women have learned to express and communicate compassion with greater ease than men.6

Research shows that, in societies that don’t socialize boys and men to pay attention to their emotions, males experience more difficulty than females when they seek to identify their emotions, attaching terms such as fear, anger, and love, to “physiological states that might or might not be correlated with those emotions.” This is not “a biologically based gender difference. […] these males actually have all the same emotions, but just don’t know how to talk about them.” (Upheavals, p. 150)

Shaming & Othering the Female Body

Many cultures discourage boys from developing their emotional life, and expect that they be without need. Thus boys become ashamed of the needy part of them. “Taught that dependence on mother is bad and that maturity requires separation and self-sufficiency, males frequently learn to have shame about their own human capacities for receptivity.” (Upheavals, pp. 219-220)

We teach shame to women, too, and leave them with a false sense of empowerment that is the very source of their feeling unsafe in the world. In her TEDx talk “We Should All Be Feminists”, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie explains that the demand that men be tough leaves them with fragile egos women are to cater for by shrinking themselves. We perpetuate the belief that a woman’s success is a threat to a man, and have women cover themselves – for to be born female is to be already guilty of something. Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie uses the Nigerian expression bottom power to refer to women’s supposed power – using their sexuality to get favors from men – which, in reality, is no power: it simply means that, from time to time, a woman can tap into somebody else’s power.7

Shame is not the only by-product emotion of gender development: “development creates different paths for disgust […] often correlated with gender.” Disgust – unlike shame which focuses on the self – spreads outward. (Upheavals, pp. 220-221) When familial and cultural norms teach boys to other and over-distance themselves from girls and women, we have a breeding ground for misogyny.

Klaus Theweleit’s study Male Fantasies finds in German soldiers’ post-WWI writings “a hypertrophy of disgust misogyny […] the disgusting [is] ‘other’.”8 (Upheavals, p. 222) As Nussbaum points out, throughout history privileged groups have projected disgust properties onto so-called inferior human groups: “Jews, women, homosexuals, untouchables, lower-class people – […] Weininger made this idea explicit: the Jew is a woman.” (Upheavals, pp. 347-348)

Still according to Nussbaum, “[t]aboos surrounding sex, birth, menstruation […] express the desire to ward off something that is too physical.” (Upheavals, p. 349) Behind disgust is also a desire to keep mortality at bay since women are “closely linked, through birth, with the mortality of the body.” (Upheavals, p. 348) Encouraging such projection reactions hinders the development of compassion: “disgust is […] likely to pose a particular threat to compassion.” (Upheavals, p. 222)

One day, on a train, I overheard a conversation between two male college students. They were talking about ex-girlfriends as though they were tainted things. One of them said that he ran into an ex-girlfriend who’s now with somebody else and that he wouldn’t want to get back together with her anyway because “It’s not yours anymore – know what I mean, man?” The other one acted as if he agreed. But it was never yours to begin with. It is a she. I was shocked to hear seemingly well-educated young men – who might even consider themselves generally progressive – other, indeed dehumanize, a woman.

What Can We Do to Make the World a Kinder Place?

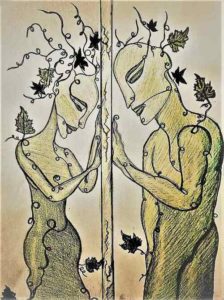

“What Vines Are Made of on the Gender Wall” by Kristina Stoyanova

We could, indeed should, make good use of the ever-changing, plastic human brain and contribute to changing the way boys and men evaluate what they consider objects of disgust. “All cognitive views of emotion entail that emotions can be modified by a change in the way one evaluates objects. […] If a person harbors misogynistic anger and hatred, the hope is held out that a change in thought will lead to changes not just in behavior but also in emotion itself.” (Upheavals, p. 232)

Refusing humanity in ourselves represents a large-scale problem that goes beyond the concerns around gender equality. The “intolerance of humanity in oneself […], connected with shame, envy, disgust, and violent repudiation, turns up […] in other prejudices […] that […] share the logic of misogyny.” Nussbaum suggests that we help fellow human beings “live with their humanity”, “learn compassion without hierarchy”, and focus on our common vulnerability. “Surrendering omnipotence is essential to compassion, and a broad compassion for one’s fellow citizens is essential to a decent society.” (Upheavals, p. 350)

In addition to fostering compassion rather than disgust and embracing our shared humanity and vulnerability, we need to develop emotional competence for boys and girls, as Chemaly suggests in her talk “The Power of Women’s Anger”. In childhood education we need to focus on individual needs, ability, and curiosity, instead of gender. Raising awareness of everyday sexism is crucial as well. Small actions men can take as allies include confronting someone being casually sexist. If a man walks into a restaurant with a woman and the waiter greets only him, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie suggests that the man asks the waiter, “Why haven’t you greeted her?” As she says, “Culture does not make people, people make culture.”

We could also broaden our perspective on compassion, understanding that compassion is not only “nurturance, kindness, softness, gentleness, and emotional warmth”, that just because some people engage in non-nurturing forms of compassion doesn’t mean they’re not compassionate. The “heroic acts […] in which people throw themselves into dangerous situations to help others” constitute “fierce, courageous and even aggressive forms of compassion.”

Part of the solution also lies in making more room for nuance and complexity. Despite the differences between boys and girls in terms of practices of child rearing, we all have male and female qualities. An us-versus-them mentality is detrimental to all of us for, fundamentally, a woman is a man is a human. In a story, I sometimes identify with a man, sometimes with a woman, relating to the person’s experiences, wounds of the past, etc. rather than to their gender.

Should we strive for an androgyny of sorts? Maybe when it comes to matters of the mind. Virginia Woolf and May Sarton seemed to make a case for cultivating an androgynous mind. “It is fatal to be a man or a woman pure and simple; one must be a woman-manly, or a man-womanly,” Woolf writes in A Room of One’s Own. In a similar vein, Sarton argues in Journal of a Solitude that “the ultrafeminine may be as off the beam as the ultramasculine and […] people of the greatest creativity and force as well as the greatest understanding, come near the middle of the spectrum.”

Going one step further, we could welcome greater nuance when dealing with important concepts and the victimhood narrative. According to Nussbaum, agency and victimhood are compatible for “only the capacity for agency makes victimhood tragic.” Within the context of feminist discussions, blurring this contrast entails recognizing that women are both agents and victims. Believing in women’s capacity to stand up against all forms of ill treatment is compatible indeed “with a strong concern to protect them from […] unequal treatment.” (Upheavals, p. 406) “[W]omen who demand more adequate enforcement of laws against rape and sexual harassment” are certainly not asking for society to treat them as victims unable to fight for their rights. (Upheavals, p. 413) Nussbaum puts forward that we cease to consider help condescending and compassion insulting (Upheavals, p. 408), and that we further empower women by minimizing the pressures imposed upon them. (Upheavals, p. 414)

Comedian Gilda Radner was quoted as saying, “I’d much rather be a woman than a man. Women can cry, they can wear cute clothes, and they are the first to be rescued off of sinking ships.” In truth, the lot of men isn’t much more enviable than that of women. It’s not about contending for who has it worse though. Rather, it’s about acknowledging that gender stereotypes benefit no one. Just as we restrict females’ freedom when we tell them who they can or cannot be, so too we stifle males’ potential by taking possibilities away from them. Just as we hurt boys and men when we encourage displays of macho bravado or tell them to man up, so too we hurt girls and women when we impose roles on them. The societies where men have too much shame to open up to women and share their vulnerabilities with them are the same societies where men dismiss a woman’s no as a challenge to overcome or a way of playing hard to get. When we create too stark a contrast between each other, we don’t actually listen to one another. Society plays a significant part in constructing emotions and in building mutual understanding, and it’s our responsibility to contribute to creating a safe space for all.

How Mainstream Feminism Alienates Many Women

Women too devalue women in some instances, turning into their own antagonists. Though men’s allyship and participation in the fight for gender equality is necessary, women ought to realize that self-assertion doesn’t require them to become ultramasculine. As Mary Wollstonecraft writes in A Vindication of the Rights of Woman in the 18th century, “I do not wish [women] to have power over men; but over themselves.”

There’s something liberating in recognizing that, in and of itself, there’s nothing inherently tragic about being a woman (in her TEDx talk “The Art of Being Yourself”, Caroline McHugh says “I don’t find myself tragically woman. I describe myself as a womanist, rather than a feminist”). That there’s an inner strength to draw on. That there’s nothing wrong with being called, say, nurturing. In The Source of Self-Regard, the late Toni Morrison suggests “that we pay as much attention to our nurturing sensibilities as to our ambition.”9 She discusses self-sabotage and even sororicide within the mainstream feminist movement:

Why are women, […], firing our assistants because and when they are pregnant, voting against the appointment of women deans and chairpersons, relating to maids as though they were property, turning over buses on other mothers’ black children? […], the movement comes dangerously close to an implosion of women-hating-women at worst, or a defeated disarray of cul-de-sac and mini-causes at best – all demonstrating the basest of male expectations: that any organization of women would end in a hair-pulling contest. (The Source, pp. 91-92)

Neither males nor females are a superior gender but, in Morrison’s view, both worship masculinity as a concept (and, in the late Adrienne Rich’s words, “No woman is really an insider in the institutions fathered by masculine consciousness”). Male supremacy includes not only men but also male-minded or male-dominated women. Women with a masculine mindset include women who don’t work towards changing laws that oppress people unlike themselves. Among the forces that divide women are racism and class stratification and, still according to Morrison, we need to sever both for male supremacy to collapse. (The Source, p. 93)

Truly eradicating sexism entails recognizing that sexism is inseparable from racism and other important considerations, and seeking to eliminate inequity on various fronts: “class inequality exacerbates the differences between black and white women, poor and rich women, old and young women, single welfare mothers and single employed mothers. Its pits women against one another in male-invented differences of opinion – differences that determine who shall work, who shall be well-educated, who controls the womb and/or the vagina; who goes to jail; who lives where.” (The Source, p. 94)

Some women have shown reluctance to fully embrace the term feminist because they don’t have much of a voice in dominant discourses. Feminism – or, more specifically, mainstream feminism – is a flawed movement because it’s made of humans and humans are flawed. Often, “[movements] are associated only with the most visible figures, the people with the biggest platforms and the loudest, most provocative voices.” (BF, Introduction x) As a result, the mainstream feminist project has become elitist: it tends to divide its members, not unite them.

We need to make sure that, when we advocate women’s rights, we don’t actually advocate some women’s rights. A step forward would be of course to better include minority groups in feminist concerns and cultural conversations – i.e. women of color, queer and transgender women, women living in developing countries and women with different religious and cultural backgrounds (“Western opinions on the hijab or burkas are rather irrelevant. We don’t get to decide for Muslim women what does or does not oppress them.” [BF, p. 104]).

Illustration by Jayde Perkin

Why not make more room for voices showing that you don’t have to belong to a certain demographic or meet a narrow set of criteria to be a good feminist, that you can be a bad feminist according to mainstream feminism but a great feminist nonetheless? Why not allow for more multidimensions and individuality, more diversity, and for people owning up to their apparent contradictions? You can be quiet and spunky simultaneously. You can have an interest in fashion and make-up and still work toward equal pay. You can be a mother working part time while supporting women’s access to all kinds of career opportunities and women’s freedom to choose whether or not to bear children. After all, what we want is nothing more than fair treatment for everyone and for us all to feel safe and worthy in all areas of life.

“Fight for the things that you care about, but do it in a way that will lead others to join you.”

Ruth Bader Ginsburg

Work in Progress

Progress has been made (though not uniformly across the globe):

- End November 2020, Scotland became the first country to make period products free

- France introduced a new law in September 2020. To ensure compliance with restraining orders, Judges can now request that domestic abusers wear electronic bracelets tracking their movements. In this way, the GPS device in the bracelet can alert the victim – also equipped with a device – that the abuser is getting closer. Spain has been using such electronic bracelets for years

- In 2018 Iceland became the first country to enforce equal pay between men and women

- Sweden has generous Parental Leave Policies and parental benefits

We still have a lot on our plate. A great many issues pertain to the topic of gender equality and are worth addressing:

- workplace harassment;

- gender wage gap;

- gender binary;

- the need for stricter policies and measures when it comes to curbing domestic violence;

- reproductive freedom, women putting their lives at risk to terminate unwanted pregnancies when abortion is illegal or unaffordable (BF, p. 278), and how female bodies are negotiable and legislated;

- voluntary childlessness (see e.g. Sheila Heti’s Motherhood);

- the impact of motherhood on artistic work (please read Rufi Thorpe’s essay “Mother, Writer, Monster, Maid”, a quick yet incisive read on how a mother can strike a balance between selflessness and selfishness) and on self-realization (among works of fiction, I’d recommend Michael Cunningham’s The Hours and Doris Lessing’s “To Room Nineteen” which were the subject of my MA dissertation);

- the oppression of women globally (see Sheryl WuDunn’s TED talk “Our Century’s Greatest Injustice”);

- how sexism shapes human knowledge;

- women bringing other women down (I remember that time a female passenger said, “that’s why women shouldn’t be at the wheel!” loud enough for the female bus driver to hear. The driver had just stopped the bus before its usual stop because of construction work – in other words, she had just done her job!);

- the tyranny of beauty, and how we lead girls to self-harm and raise them to believe their greatest assets are marketable façades (see Katie Makkai’s hard-hitting slam poem “Pretty”);

- the lack of representation of women in certain professions;

- the connection between gender justice and care for dependents, which Nussbaum addresses in Frontiers of Justice: Disability, Nationality, Species Membership. Women do most of the unpaid care work, and caregivers need “recognition that what they are doing is work; assistance, both human and financial; opportunities for rewarding employment and for participation in social and political life.”10 According to Nussbaum, one could draw a parallel between the case of citizens with disabilities and the cases of race and sex because of the discriminatory social arrangements in place. People with hearing and visual impairments and wheelchair-users can be “productive members of society in the usual economic sense, […], if only society adjusts its background conditions to include them.” (Frontiers, p. 113);

- …

To delve deeper into sexual violence, women on television, women’s anger, and everyday sexism, which I’ve only touched upon, you may want to read Lynn Higgins & Brenda Silver’s Rape and Representation, Reality Bites Back: The Troubling Truth about Guilty Pleasure TV by Jennifer Pozner, Soraya Chemaly’s Rage Becomes Her and Rebecca Trainster’s Good and Mad: The Revolutionary Power of Women’s Anger, and watch Laura Bates TEDx talk “Everyday Sexism”.

I’m grateful for all the people using their strengths today to advocate women’s rights and for all the people who paved the way. Some need no introduction (Malala, Gloria Steinem, Eve Ensler, Simone de Beauvoir, Audre Lorde…), others are lesser-known voices.

To name but a few women who’ve done amazing work – embarrassingly, several of these women I didn’t know about until I read the November 2019 issue of National Geographic:

- Amani Ballour, a Syrian pediatrician who, amid war-torn Syria, treated victims beneath a hospital under construction which became known as the Cave;

- the late Aya Aghabi, Jordan’s biggest accessibility champion;

- the late Wangari Maathai, the first African woman to win the Nobel Prize and founder of the Green Belt Movement, an NGO focused on planting trees, protecting the environment, and fighting for women’s rights;

- Vera Danchakoff, Russian pioneer in stem cell research in the 1900s;

- Abolitionist Sojourner Truth, who gave the speech “Ain’t I a Woman?” when the campaign for woman suffrage overlooked Black women;

- Barbara Smith, an important Black feminist voice;

- Robin Morgan and her sisterhood anthologies;

- Aneeta Rattan who studies i.a. “mindsets that promote belonging, commitment, and achievement among minorities and women in domains where they are underrepresented and negatively stereotyped” and “mindsets shap[ing] individuals’, organizations’, and societies’ ability to foster positive interactions among diverse group members (across gender, race/ethnicity, and sexual orientation status)”

- Sociologist Judy Wajcman whose research focuses on technofeminism;

- Kate Manne who, in her book Down Girl: The Logic of Misogyny, coined the term “himpathy”;

- Sophia Amoruso, founder of Girlboss media;

- Sairee Chahal, founder of SHEROES;

- Asha de Vos Sri Lankan, pioneer of blue whale research;

- Paula Kahumbu, advocate for wildlife and the protection of elephants in particular;

- Ajay Patel and Usha Vishwakarma who in 2011 formed the Red Brigade Trust, an Indian NGO that teaches self-defense for women to protect themselves against sexual assault

The list could go on and on. Let’s work towards making it so extensive it grows into an encyclopedia-sized book of names that have helped build a more equitable world!

We can find people striving to empower women in our immediate circle of friends and acquaintances. Annie Sisson, for instance, is one such source of inspiration I’m lucky to know. Annie explains how travel helps her connect with other women and constitutes a significant part of her bold life:

From the moment I stepped off my first overseas flight in 2008, I was hooked. Immediately, I knew it would be a cornerstone of my life. After those first few days wandering around Stockholm, Sweden on my own, I also knew these experiences were meant to be shared. In the years since, travel has been a powerful way for me to connect with other like-minded women, both those I started my journey with and new friends I met along the way. There’s something about being completely out of your comfort zone and daily routines that makes us more willing to open ourselves up to new people and conversations. So many of us want to explore, but the stigma and vulnerability of a woman traveling alone can be a concern. However, traveling alone or with other women is when I feel like a total badass! Roadtripping through foreign lands with a girlfriend or getting comfortable having dinner alone helps us see how courageous we truly are. All of us women have heard the stories about how weak, vulnerable, incapable, emotional, and silly we are. Intentionally stepping out of our comfort zones in order to make one of our dreams come true is one of the most empowering moments we can give ourselves. It’s worth it. Every damn time.

Please visit Annie’s website here

|

Annie’s mission in her own words: I’m a multi-passionate entrepreneur whose work focuses on helping women find their inner badass and create lives they’re excited to wake up to every day. I use my wide range of skills to create opportunities for women to discover more of themselves, whether gathering together for unique travel experiences or coaching women to bust through their limiting beliefs and old stories that hold them back. My brand, Into the Bold, was born through my own journey from unempowered woman to self-love and acceptance. |

Here’s to you being a force for good, too! Thank you so much for having taken the time to read this post. Please don’t hesitate to leave a comment below

1. I’ll use the spelling women rather than womxn throughout this post to avoid any confusion as I’ll quote authors who use this spelling. By women, I mean all people who identify as women, including trans and nonbinary women.↩

2. Soraya Chemaly, “The Power of Women’s Anger.” TED. https://www.ted.com/talks/soraya_chemaly_the_power_of_women_s_anger (accessed April 12, 2021).↩

3. Roxane Gay, Bad Feminist: Essays (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2014), p. 72. All references are to this edition. Further cited in the text and abbreviated to BF in the quotations.↩

4. Martha C. Nussbaum, Upheavals of Thought: The Intelligence of Emotions (New York: Cambridge University Press), pp. 376-377. All references are to this edition. Further cited in the text and shortened to Upheavals in the quotations.↩

5. Emma Seppälä, “The Surprising Key to Relationship Success.” Psychology Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/feeling-it/201609/the-surprising-key-relationship-success (accessed April 12, 2021). See also Prof. Ari Berkowitz’s article “Brain scientists haven’t been able to find major differences between women’s and men’s brains, despite over a century of searching” on The Conversation: “any sex differences in brain structures are most likely due to a complex and interacting combination of genes, hormones and learning.”↩

6. Emma Seppälä, “Are Women Really More Compassionate?” Psychology Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/feeling-it/201306/are-women-really-more-compassionate (accessed April 12, 2021).↩

7. Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, “We Should All Be Feminists.” TED. https://www.ted.com/talks/chimamanda_ngozi_adichie_we_should_all_be_feminists (accessed April 12, 2021).↩

8. “while at some level the bodies of all women […] are objects of disgust, at the level of conscious conceptualization there is a sharp splitting – wives, mothers, and nurses being represented as pure and ‘white’, prostitutes and working-class women as sticky and disgusting.” (Upheavals, p. 222)↩

9. Toni Morrison, The Source of Self-Regard: Selected Essays, Speeches, and Meditations (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2019), p. 111. All references are to this edition. Further cited in the text and shortened to The Source in the quotations.↩

10. Martha C. Nussbaum, Frontiers of Justice: Disability. Nationality. Species Membership (Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2007), p. 100. Further cited in the text and shortened to Frontiers in the quotations.↩

Thanks to the author for giving us this very thorough study of the problem with a passionate, yet impartial attitude to the progress of all women. I hope both women and men are going to read it so we can all take steps to gender equality which should spring from an understanding of the innate value of all human beings. Looking forward to reading more on the problem by the same author.