Preliminary Remarks

– This post is so made that you can click on any section you like without having to read the whole post. To further improve its readability, I’ll use the words “humans” and “animals” throughout the post, although it’s more accurate to speak of “human animals” and “nonhuman animals.” You’ll also find illustrations as beautiful complement. I’ve put some passages in bold as well, so you can skim the post and still get the gist.

– At EU level, developments in animal law are promising, and we seem to adopt more appropriate penalties for animal cruelty. Still I won’t expand on the efforts we’ve made for two main reasons. I acknowledge and applaud the progress, but a) highlighting what we’ve done so far can cause us to overlook what we still need to do and experience something akin to the “bystander effect,” and b) some countries aren’t complying with EU bans. (In the U.S., the lack of enforcement of the barely-there animal regulations is such that no one can prosecute factory farms for violation, as discussed in ‘Concrete Ways to Help.’)

Right – I’ll leave you to it 😀

(Post photo by Santi Ohara)

Why

THE WAY THINGS ARE

Intersections

Dirty Money, Clean Conscience

Filet Mignoning Reality

A Day at the Madhouse

Animals' Needs for Flourishing

The Many Similarities between Humans and Animals

Animals as Therapists and Teachers

Tapping into the Goodness in People

Blurring the Line between Thinking and Feeling

If Animals Could Speak

Animal Testing & Other Issues

Imaginary Earpiece

THE WAY OUT

Making New Madeleines

Alternatives to Eating Animals

Concrete Ways to Help

Inspiration from Abroad

A Common Vision

Cultivating Compassion

Wonder

Last Word

Why

Why

1994, Cornell University. Carl Sagan gives a beautiful, humbling speech about our “mote of dust suspended in sunbeam.” A quarter of a century later, it still resonates. In fact, Sagan’s words have inspired both the title of this post and its core message. We have a “responsibility to deal more kindly with one another, and to preserve and cherish the pale blue dot, the only home we’ve ever known.” In the vast cosmic dark surrounding our tiny planet, “there is no hint that help will come from elsewhere to save us from ourselves.”1

Why did I decide to write this post?

Four main reasons

I want to:

- lend a voice to animals

- contribute to making veganism friendlier

- help create a more compassionate and connected world

- underline the urgency of the issue of industrial farming and, by extension, animal abuse

1. Lending a Voice to Animals

Did you know that sea otters hold hands while sleeping not to drift apart? that bearcats’ urine smells like hot-buttered popcorn? that frogs can see color in the dark? or that good-humored rats giggle when you tickle them?

The truth is, we hardly know anything about animals. We’ve underestimated how intelligent, sensitive, beautiful, fun, and altogether wonderful they are.

2. Making Veganism Friendlier

I sometimes disagree with the way veganism is promoted. We tend to view vegans as either kill-joys or neo-hippies (there’s nothing wrong with being a hippie – I’ll explain what I mean in a minute). I’d love to see more inclusiveness.

Approachability

In a 2009 interview with Jon Stewart, Jane Goodall revealed “fundamentalists” accused her of lighting candles on her birthday. The cake probably had animal products and the candles beeswax. It’s counterproductive (and rude) to antagonize and shame people. If we want to mainstream veganism and reach a larger audience, we need to choose kindness always.

As research scientist Amanda Askell says, “the thing that people mainly find off-putting about social justice activists is the methods of engagement of some of them. And maybe some people feel, […], attacked when they just don’t understand these issues or they want to get to know them […] being a bit more careful about how things are presented would be good because you can alienate potential allies.”2

So a few vegans are extremists. That said, we’re sometimes too quick to label people, without knowing the whole story. For instance, the ALF that aim to free animals, cause economic damage and raise awareness about animal abuse, have never harmed or killed anyone with their actions and define themselves as a non-violent group.3 We tend to muzzle all those who, using their constitutional freedom of speech, oppose certain abuses committed on animals. Thus the violent actions of a few act as a threat. (Jeangène Vilmer, p.162) The risk, then, is to conflate an extreme fringe with the movements of defense and animal liberation in general. (Jeangène Vilmer, p.165)

When I shop for myself, I buy vegan food. However, I eat vegetarian on people’s birthdays, at weddings, etc. if cooking vegan is too much of a fuss for the hosts. If someone gives you a sweater as a present and it has a bit of wool in it, it’s respectful to thank her. Likewise, it’s okay for your neighbor to have a laying hen in his garden, if he doesn’t make a business out of it. And I think it’s a good thing that big retailers offer vegan options. It’s possible to be flexible without compromising our ideals. It’s important that our efforts head to a constructive direction, but we need greater tolerance of one another, from both sides. Still according to Amanda Askell, we lack moral empathy, i.e. the ability to “get inside the mindset of someone who expresses views that we disagree with and see that from their point of view.” She gives the example of people getting annoyed with their so-called picky vegetarian family member who doesn’t eat meat at a family gathering.2

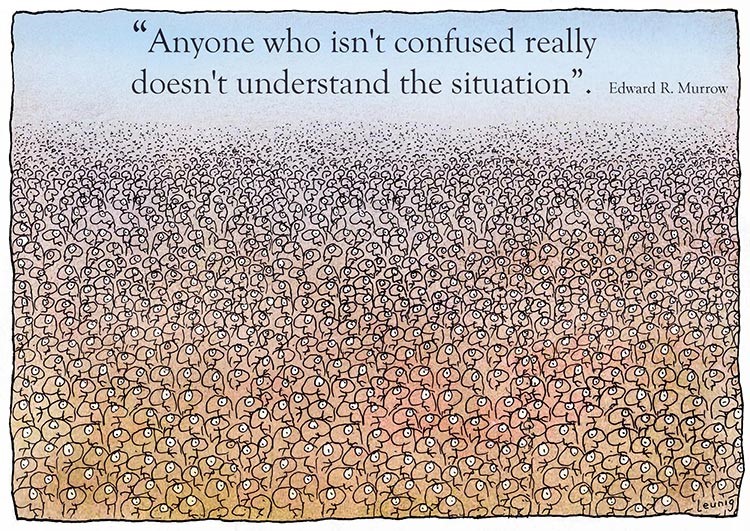

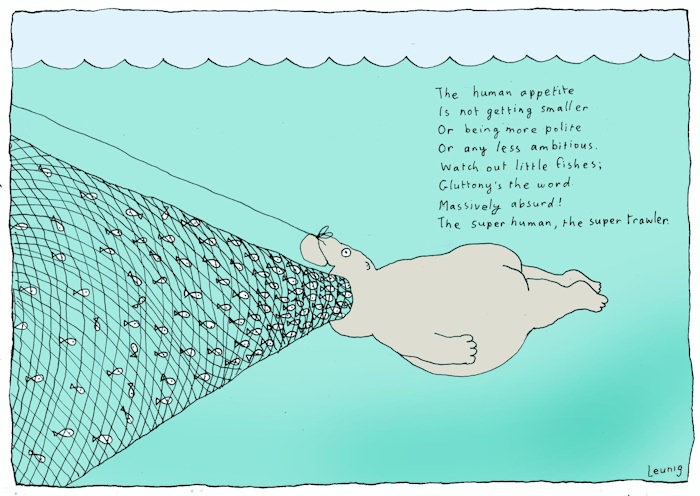

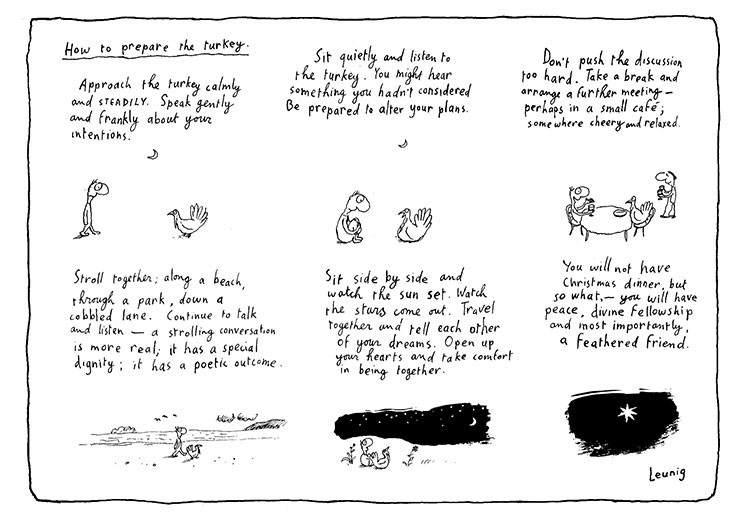

Image courtesy of Michael Leunig

Accessibility

I want to portray veganism as something easily accessible and affordable as well. That’s why, as strange as it may sound, I won’t overemphasize the importance of health. Focusing on it doesn’t seem to help make it attractive enough. Research at Stanford and Johns Hopkins shows that “once you call something a health product, consumer acceptance goes down. […] If you say that something is healthy or healthier than something else, people assume they’re giving something up.”4 Many of us either look at near-perfect wellness gurus striking yoga poses on the beach and think of such lifestyle as an unattainable ideal or ridicule happy salad eaters. (Search for “woman laughing alone with salad meme.”) I hope this post will help sort of debunk some myths, and facilitate the inclusion of people with different backgrounds, views, interests, shapes and sizes.

3. A Compassionate and Connected World

We’re bundles of contradictions, aren’t we? That makes us interesting. Yet in some cases that can cause our downfall. People seem to be future-oriented and quick to embrace modern and progressive ideas when it comes to tech gadgets (wanting to buy the latest phone, and the like), but cite the way their ancestors lived to justify their eating meat, enslaving themselves in the name of tradition.

There seems to be a split between our intelligent brain (which sends people to the moon, and makes them do incredible things) and our compassion.5

Children naturally love animals. Who hasn’t gone through an “I want to become a vet” phase? Recently, as I was doing my grocery shopping, I noticed a little boy in front of the lobster tank in the supermarket. His hands on the glass, almost pressing his face against it. He was observing the lobsters, as I used to as a child, with a mix of fascination and compassion, perhaps torn between quiet acceptance of the lobsters’ fate and an impulse to free them. Meanwhile, everyone else was rushing from one row of products to the next, oblivious. I don’t mean that we should regress to childhood, but I do think we could (re)learn to be compassionate.

Why don’t we care as much as we used to? If compassion is natural, why does it require effort once we become adults? Animals are nameless and voiceless. Especially in the case of factory-farmed animals, they’re just too numerous. “The problem posed by meat has become an abstract one: there is no individual animal, no singular look of joy or suffering, […]. The philosopher Elaine Scarry has observed that ‘beauty always takes place in the particular.’ Cruelty, on the other hand, prefers abstraction.”6As Bertolt Brecht wrote, when crimes come like falling rain, they become invisible and smother our cries. So we don’t speak out:

[…]

The first time it was reported that our friends were being butchered there was a cry of horror. Then a hundred were butchered. But when a thousand were butchered and there was no end to the butchery, a blanket of silence spread.

When evil-doing comes like falling rain, nobody calls out “stop!” When crimes begin to pile up they become invisible. When sufferings become unendurable the cries are no longer heard. The cries, too, fall like rain in summer.

– extract from “When Evil-Doing Comes Like Falling Rain” by Bertolt Brecht

Image by Free-Photos from Pixabay

We need to reassess our duties, and care not just within our narrow realm but beyond it as well. As Martha Nussbaum puts it in Frontiers of Justice,

Traditional moralities hold that it is wrong to harm another by aggression or fraud, but that letting people perish of hunger or disease is not morally problematic, […]. We have a strict duty not to commit bad acts, but we have no correspondingly strict duty to stop hunger or disease or to give money to promote their cessation. […] the very idea of a benevolent despotism of humans over animals, […], is morally repugnant: the sovereignty of species, like the sovereignty of nations, has moral weight.7

4. Urgency

I’ll start with some figures to help you measure the extent of the problem, before explaining the structure of the post.

Some Figures

The Open Philanthropy Project team select cause areas according to importance, tractability and neglectedness, and “farm animal welfare lined up on all three of those criteria.”8

Yuval Noah Harari suggests that “the treatment of domesticated animals in industrial farms is perhaps the worst crime in history. […] the agricultural revolution created completely new kinds of suffering, ones that only worsened with the passing of the generations.” Throughout history, humanity has changed both animal populations and their living conditions. Because of that, the animal kingdom has lost much of its variety. “Today, more than 90% of all large animals are domesticated.”9

This Faunalytics report by Bas Sanders, based on data from the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations, reveals that, worldwide, humans kill more than 70 billion land animals for food every year,10 with chickens being the most slaughtered animal, and that “from 1961 to 2016 the number of slaughtered animals has increased for all the animal types.”11 As for fish, “there’s somewhere between 35 billion and 140 billion farmed fish, at any point in time. […] if you’re also concerned about wild caught fish, the numbers could be in the trillions.”8

Photo by Quentin Kemmel on Unsplash

33% of our Planet’s croplands are used to feed livestock feed12 which uses up 45% of world water (the equivalent of taking a shower for one year).5 New research by Greenpeace revealed earlier this year that over 71% of the EU’s farmland is dedicated to livestock feed production. Every year the EU spends on the animal farming sector 18-20% of its total budget. In other words, the EU uses up to a fifth of its annual budget to keep destroying our already fragile Earth and its scarce resources.13 You can find the complete report here. In the US, where a considerable part of our land animals are slaughtered14 and eaten,15 the figures could be even more shocking.

While we waste billions on livestock feed and on further enriching the wealthy meat industry, we spend very little money on stopping the mass killing and consumption of animals.8 Today, almost all the animal products humans eat – the figures verge on 100% for all the most in demand farmed animals – come from animal factories. (Jeangène Vilmer, p.170; Foer, p.109) Even if it seems supermarkets offer us more alternatives to animal products, we keep increasing our livestock production on an alarming scale. And “even though per capita meat consumption is down slightly from 7 years ago, it is going back up and because people are shifting from beef to chicken, the raw numbers of animals and consequently the amount of animal suffering is at an all time high.”4

“By 2050, the world’s livestock will consume as much food as four billion people.” (Foer, p.262) The UN also expects the depletion of fish stocks (Foer, pp.176-177) as well as a doubling of meat and milk world production (Jeangène Vilmer, p.169) by the same date.

THE WAY THINGS ARE

In the first part of this post, ‘The Way Things Are,’ I’ll expose the health and environmental hazards of animal husbandry as well as its role in widening the gap between the rich and the poor (cf. ‘Intersections’).

The question of justice for animals is all-encompassing indeed.16 It’s an issue that magnifies many of the world’s problems: threats to worldwide health, global poverty, infringement of human rights, pollution, climate change and our crumbling ecosystem. If you care about any of these questions, then you care about animal rights – even if you don’t know it yet.

In ‘Dirty Money, Clean Conscience,’ I’ll address the competition between large corporations to manufacture the cheapest possible meat. Consumers reward greed-driven factory farms, encouraging them to keep up with both technology to develop their assembly-line methods of production and an ever more frantic pace.

In ‘Filet Mignoning Reality,’ I’ll tackle the various forms of communication we use to banalize animal cruelty.

‘A Day at the Madhouse’ is an exploration of everyday farming and slaughterhouse practices. My aim isn’t to enumerate the countless acts of cruelty to animals reared and killed for food but, since they are the rule rather than the exception, not reporting on them would mean leaving out a huge feature of the system.

It’s important to shed light on the inherent cruelty of industrial farming. As Bruce Friedrich, co-founder of the Good Food Institute, points out, “people are supporting cruelty to animals that would warrant felony, cruelty to animals charges if dogs or cats were similarly abused.”4

Intensive confinement stifles animals’ instinctive behaviors and capabilities, and blatantly ignores their needs for a full, dignified life, as will be discussed in ‘Animals’ Needs for Flourishing.’ We often say it’s cruel of us to treat animals poorly, but I think we should say more often that it’s also insulting and degrading and condescending to them.

Animals feel joy, fear, grief, and other strong emotions humans share with them. Though we’ve marginalized animals, our commonality shows through our history (I’m not only referring to biology and evolution but also to the joint suffering of oppressed groups)17 and through animals’ intricate thought patterns, complex psychology and social sophistication (cf. ‘The Many Similarities between Humans and Animals’), as empirical evidence shows.

While seeking to create a greater sense of commonness by looking into our interaction and relation with our fellow living creatures, I want to bring out animals’ otherness as something valuable and beautiful. To me, our mistreatment of animals reflects our general low tolerance for differentness. I want to help change that because everyone deserves equal treatment and opportunities.

As Peter Singer argues in Animal Liberation, “the claim to equality does not depend on intelligence, moral capacity, physical strength, […]. Equality is […] not an assertion of fact.” Animals are differently abled and differently built, but that doesn’t mean we can’t give equal consideration to their needs and interests.18

As a matter of fact, some animals surpass us in that they can more readily show unguarded love and enormous vulnerability despite past hurts, continue to play as adults, and gently resolve conflicts among other things. They’re also precious allies when we’re going through trying times. This will be explained in ‘Animals as Therapists and Teachers.’ Jeremy Bentham said, “Each to count for one and none for more than one.” The time is more than ripe for us to cultivate humility.

‘Tapping into the Goodness in People’ will underscore humans’ instinctive compassion and its crucial role in counterbalancing shame and disgust. The disgusting is someone or something different from us that we consider base, which further suggests that we tend to resist embracing both differentness and our own vulnerability. Humans are truly good at heart, but many have lost touch with their compassion and need to reclaim it.

In ‘Blurring the Line between Thinking and Feeling,’ I’ll discuss how emotions are far from standing in contrast with thoughts, and suggest that we rethink language by drawing on Martha Nussbaum’s flexible, nonlinguistic account of cognition in Upheavals of Thought (cf. ‘If Animals Could Speak’). If animals weren’t nonverbal creatures, they would have taken us down a peg long ago. Yet they are “mute,” and I’ll outline the reasons why this shouldn’t stand in the way of their emancipation.

I’ll also call attention to the impressive, surprising and sophisticated forms of communication they use to communicate both with each other and with humans.

In ‘Animal Testing & Other Issues,’ I’ll address other forms of animal abuse, including animal experimentation for which we pay taxes, allowing “the sacrifice of the most important interests of members of other species in order to promote the most trivial interests of our own species.” (Singer, p.9) We need to denounce all practices that, rather than serve as an outlet for human violence, fuel it.

I consider these issues vitally important, but will give more space to factory farming since the animals killed for food consumption are 100 times more than the sum of all the animals killed in all other sectors (hunting, fur, animal experimentation). (Jeangène Vilmer, p.169) I hope that, when we put an end to industrial livestock production, we will, inevitably, abolish all other forms of animal abuse because they intertwine. I hope that in the not-too-distant future, we will cease to wear ‘authentic leather’ as a badge of honor and instead will have the courage to own up to our mistakes and fix them.

Closing the first part, ‘Imaginary Earpiece’ contains questions or remarks vegans frequently hear and suggested responses.

THE WAY OUT

In the second part of this post, ‘The Way Out,’ I’ll offer some concrete avenues to try and determine the best course of action.

In ‘Making New Madeleines,’ I’ll discuss our attachment to childhood memories and what changing our eating habits evokes for us. I hope to show you that you don’t have to give up madeleines or any treat you like: we can fall back into childhood anytime or indulge in decadent meals with our loved ones without harming anyone.

‘Alternatives to Eating Animals’ will have a look at both plant foods and clean meat.

A former colleague once told me that he makes his daughter taste spices and guess the separate flavors when they cook. That’s amazing but, if your childhood was anything like mine, that’s not what your early experiences in the kitchen looked like.

At our home, the kitchen was a battlefield at worst (no one wanted to prepare the damn dinner, but everyone had to get down to it) and a ‘grab and go’ passage place at best : ) The dining room table was like a second desk to me, the place where I’d do my homework to the sound of the television.

After my father’s death, my mother raised her four kids single-handedly while working hard to make ends meet. She’d buy items on sale and family-size packs, and we’d have bread with usually cheese or meat for lunch. My mother is a busy, strong-willed woman, reminiscent of Kristin Scott Thomas’s character in The Horse Whisperer – the way she vigorously brushes her short hair, her inability to sit still, how she smoothes out the tablecloth when her daughter leaves the dinner table, how she sometimes lets her cope on her own instead of overprotecting her.

But some things could have predicted my becoming contemplative-ish and caring about the whole world immensely: we were surrounded by animals (they were just like family members), and my mother is a humanitarian. She’d choke back tears when we’d watch the news. The most selfless human being I know, she’s always put others first.

I used to think you had to be a bit highfalutin to go to organic shops. Still today I feel somewhat awkward when I shop there, and I’m not one for spending hours in the kitchen. Thankfully, it’s possible to be vegan while living on a budget, and to reconcile a demanding schedule with healthy eating habits.

I became a vegetarian a decade ago and have been a vegan for a few years. If you’re flirting with the idea of cutting out meat and fish too, I hope to show you that it’s possible to make new choices and not look back with regret. Chances are you won’t be sorry. If anything, you’ll wish you’d done it earlier.

It makes sense to start here, if you want to contribute to ending the carnage, as “[d]eciding what to eat […] is the founding act of production and consumption that shapes all others.” (Foer, p.258) At the same time you may help in many other ways, adopting a holistic approach to the issue at hand (cf. ‘Concrete Ways to Help’).

We’ll also draw inspiration from other countries in ‘Inspiration from Abroad’ as a first baby step to sort of sketching a common vision (cf. ‘A Common Vision’).

In ‘Cultivating Compassion,’ we’ll see how we can educate ourselves and others as individuals (through the arts and imaginative play, among other things) and as part of a citizenry (by shaping the institutional design) and how we can cultivate compassion more specifically. We’ll see how important early social teaching is since early memories shape our emotional life as adults.19 In ‘Wonder,’ I’ll encourage you to have deeper awareness of and gratitude for the world around you and all its little things, and to wonder at the possibilities that lie ahead.

I’ll close the whole post by inviting you to be optimistic, courageous and vulnerable, to both take part in a real, shame-free conversation and act with greater consciousness and passion in your daily life. (cf. ‘Last Word’).

I’ll state facts throughout this post, but won’t over-rely on them. I am emotionally committed, and hope you’ll come to see emotional commitment as something acceptable and even necessary. To paraphrase Helmut F. Kaplan, who has an emotional disorder? He who, in the face of horror, has emotions and expresses them or he who, in the face of the most vile crime, remains as impassive as a robot?20

1. Carl Sagan, “Pale Blue Dot.” The Planetary Society. http://www.planetary.org/explore/space-topics/earth/pale-blue-dot.html (accessed August 14th, 2019).

2. Robert Wiblin; Keiran Harris, “Tackling the Ethics of Infinity, Being Clueless about the Effects of our Actions, and Having Moral Empathy for Intellectual Adversaries, with Philosopher Dr Amanda Askell.” 80,000 Hours. https://80000hours.org/podcast/episodes/amanda-askell-moral-empathy/ (accessed August 14th, 2019).

3. Jean-Baptiste Jeangène Vilmer, Ethique animale (Paris: Presse Universitaires de France, 2008), pp.156-160. All references are to this edition. Further cited in the text and shortened to author’s name and page number.

4. Robert Wiblin; Keiran Harris, “Bruce Friedrich Makes the Case that Inventing Outstanding Meat Replacements is the Most Effective Way to Help Animals.” 80,000 Hours. https://80000hours.org/podcast/episodes/bruce-friedrich-good-food-institute/ (accessed August 14th, 2019).

5. LoveMEATender. Dir. Manu Coeman. AT-Production, 2011.

6. Jonathan Safran Foer, Eating Animals (New York: Back Bay Books, 2010), p.102. All references are to this edition. Further cited in the text and shortened to author’s name and page number.

7. Martha C. Nussbaum Frontiers of Justice: Disability. Nationality. Species Membership (Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2007), p.372-373.

8. Robert Wiblin, “Ending Factory Farming as Soon as Possible.” 80,000 Hours. https://80000hours.org/podcast/episodes/lewis-bollard-end-factory-farming/ (accessed July 28th, 2019).

9. Yuval Noah Harari, “Industrial Farming Is One of the Worst Crimes in History.” The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2015/sep/25/industrial-farming-one-worst-crimes-history-ethical-question (accessed July 30th, 2019). Courtesy of Guardian News and Media Ltd.

10. Regarding the number of factory-farmed land animals, “[g]lobally, roughly 450 billion land animals are now factory farmed every year.” (Foer, p.34)

11. Bas Sanders, “Global Animal Slaughter Statistics and Charts.” Faunalytics. https://faunalytics.org/global-animal-slaughter-statistics-and-charts/ (accessed July 28th, 2019).

12. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, “Livestock and Landscapes.” FAO. http://www.fao.org/3/a-ar591e.pdf (accessed July 28th, 2019).

13. Greenpeace European Unit, “Over 71% of EU Farmlands Dedicated to Meat and Dairy, New Research.” Greenpeace. https://www.greenpeace.org/eu-unit/issues/nature-food/1807/71-eu-farmland-meat-dairy/ (accessed July 28th, 2019).

14. Roman Duda, “Factory Farming.” 80,000 Hours. https://80000hours.org/problem-profiles/factory-farming/ (accessed July 28th, 2019).

15. The U.S. slaughters about 9 billion animals yearly. 98.5% of them are birds. (Wiblin and Harris, “Bruce Friedrich Makes the Case.”) / “If the world followed America’s lead, it would consume over 165 billion chickens annually.” (Foer, p.148)

16. A hamburger would cost € 200, if we took into account the costs related to public health, the environment, etc. (LoveMEATender. Dir. Manu Coeman.)

17. As Martha Nussbaum points out, “[t]he meat industry brings countless animals into the world who would never have existed but for that. To John Coetzee’s fictional character Elizabeth Costello, in The Lives of Animals, […]: it ‘dwarfs’ the Third Reich because ‘ours is an enterprise without end, self-regenerating, bringing rabbits, rats, poultry, livestock ceaselessly into the world for the purpose of killing them.’” (Nussbaum, Frontiers, p.345)

18. Peter Singer, Animal Liberation (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2009), pp.4-5. / Humans can be widely different from each other: “humans come in different shapes and sizes; […], if the demand for equality were based on the actual equality of all human beings, we would have to stop demanding equality.” (Singer, p.3)

19. Martha C. Nussbaum, Upheavals of Thought. The Intelligence of Emotions (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003), p.6.

20. Sandrine Delorme, Le cri de la carotte (Paris: Les points sur les i, 2011 ), p.85.

THE WAY THINGS ARE

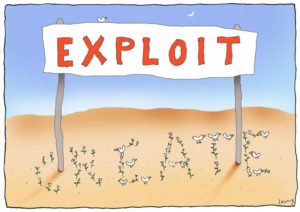

Image courtesy of Michael Leunig

Intersections

Intersections

Health

The excesses of factory farming have a twofold human cost: humans pay the price for abusing animals at both an individual and a global level. The products we give to animals, such as antibiotics,1 can be found in the meat we eat, and intensive animal farming (more specifically, the sanitary conditions of factory farms and the long-distance transport) in the age of globalization means that the risk of epizootic diseases and pandemic is high. (Jeangène Vilmer, pp.174-175)

Scientists have predicted new viruses moving between farmed animals and humans in the near future.2 After swine fever, mad cow and foot-and-mouth disease, and the avian flu, a superpathogen or “a hybrid virus that could cause a repeat, […], of the Spanish flu of 1918” is expected to threaten global health soon. (Foer, p.138)

Scientists trace the source of flu strains to migrating aquatic birds that carry these viruses, and “shed them through feces into lakes, rivers, ponds, and, […], thanks to industrial animal-processing techniques, directly into [our] food.” It becomes problematic when a virus in one species mixes with viruses in others and trade genes, “as H1N1 has done (combining bird, pig, and human viruses). […] pigs are susceptible to the type of viruses that attack birds as well as to those that attack humans.” (Foer, pp.127-128)

The “vehicle of transmission” of food-borne illnesses “is, overwhelmingly, an animal product.” (Foer, pp.138-139) The poultry industry in particular is a breeding ground for bacteria and pathogens:

Scientific studies and government records suggest that virtually all […] chickens become infected with E. coli […] and between 39 and 75 percent of chickens in retail stores are still infected. Around 8 percent of birds become infected with salmonella […]. Seventy to 90 percent are infected with another potentially deadly pathogen, campylobacter. Chlorine baths3 are commonly used to remove slime, odor, and bacteria. […] the birds will be injected […] with “broths” and salty solutions to give them what we have come to think of as the chicken look, smell, and taste. (Foer, p.131)

To compensate for their compromised immunity, factory farms have animals ingest drugs and feed additives at every meal, and give them an astronomical amount of antibiotics nontherapeutically, while “study after study has shown that antimicrobial resistance follows quickly on the heels of the introduction of new drugs on factory farms.” (Foer, p.140) The increasingly antimicrobial-resistant pathogens appear to spring from this excessive nontherapeutic antibiotic use. (Foer, p.141)

Not only would vegetarianism effectively help us protect public health at a global level, but it would also improve every individual’s health in myriad ways. According to the American Dietic Association,

[w]ell-planned vegetarian diets are appropriate for all individuals during all stages of the life cycle, including pregnancy, lactation, infancy, childhood, and adolescence, and for athletes4 […] tend to be lower in saturated fat and cholesterol, and have higher levels of dietary fiber, magnesium and potassium, vitamins C and E, folate, carotenoids, flavonoids, and […] are often associated with […] lower risk of heart disease […] lower blood pressure levels, and lower risk of hypertension and type 2 diabetes. Vegetarians tend to have a lower body mass index […] and lower overall cancer rates. (Foer, pp.144-145)

Many people are reluctant to cut out animal products because they worry about protein deficiency. Yet the American Dietic Association confirms that vegetarians and vegans meet requirements for protein. Moreover, nutritional data showed that “excess animal protein intake5 is linked with osteoporosis, kidney disease, calcium stones in the urinary tract, and some cancers. […] vegetarians and vegans tend to have more optimal protein consumption than omnivores.” (Foer, p.144)

In a similar way, we need to watch our dairy intake. Marion Nestle, a public health professional, “notes that in parts of the world where milk is not a staple of the diet, people often have less osteoporosis and fewer bone fractures […]. The highest rates of osteoporosis are seen in countries where people consume the most dairy foods.” (Foer, p.147)

Both for animals’ sake and our own, experts confirm that we need to eliminate the practices of the factory farm industry: “After having a panel of renowned experts conduct a two-year study, the Pew Commission […] argu[ed] for the complete phaseout of several common ‘intensive and inhumane practices,’ citing benefits to both animal welfare and public health.” (Foer, p.180)

Environment

With 14.5% of global greenhouse gas emissions according to the FAO,6 animal agriculture is the leading cause of climate change, “mak[ing] a 40% greater contribution to global warming than all transportation in the world combined.” (Foer, p.43) In Bidoche, Fabrice Nicolino suggests that someone who eats vegan and organic food leaves an ecological footprint 20 times less than an average consumer: a person cutting out milk and meat only travels 281 km, if s/he consumes organic products for the rest. But an omnivore “drives” the equivalent of 4,758 km, i.e. 20 times more.7 As Jonathan Safran Foer points out, “it isn’t unusual for meat to travel almost halfway across the globe to reach your supermarket.” (Foer, p.104)

The percentages for global land and water use8 also tip the scale in favor of low carbon footprint foods, such as pulses and whole grains.6

Thus “someone who regularly eats factory-farmed animal products cannot call himself an environmentalist without divorcing that word from its meaning.” (Foer, p.59)

Producing meat and milk pollutes9 soils, air and water, contributes to acid rain, deforestation10 and climate change, and harms biodiversity. (Jeangène Vilmer, p.176)

Overfishing greatly impacts biodiversity as well, pillaging the seas: 46% of the 28,000 species of fish are threatened, and with them the entire marine ecosystem.11 (Jeangène Vilmer, pp.176-177)

Photo by Ian Schneider on Unsplash

Manure, when it reaches excessive concentrations and is piled up in the same place, penetrates the soils deeply and infects groundwater, lakes and rivers, kills aquatic fauna, and even threatens drinking water. As for air pollution, it significantly impacts the health of the inhabitants of the area. (Jeangène Vilmer, p.177)

The poorly managed (and enormous amount of) manure from hog facilities in particular “seeps into rivers, lakes, and oceans – killing wildlife and polluting air, water, and land in ways devastating to human health.”12(Foer, p.174) Actually, the waste isn’t strictly manure. It “includes but is not limited to: stillborn piglets, afterbirths, dead piglets, vomit, blood, urine, antibiotic syringes, broken bottles of insecticide, hair, pus, even body parts.” (Foer, pp.175-176)

Global Poverty

Some say vegetarianism or veganism is a first-world luxury. It’s a misconception, in that in Africa, for example, meat is eaten only on special occasions. It’s a cultural, social, and human activity first and foremost rather than an economic activity.13

Also, some authors suggest that factory farming contributes to the iniquity of food distribution, widening the gap between mal- and overnutrition. Alfred Kastler suggested that vegetarianism helps combat famine as meat production uses a considerable amount of grain to feed the animals humans eat, while this grain could be used for human consumption. The amount of grain needed to feed the cattle that feeds only one person would directly feed 20 people.14 (Jeangène Vilmer, p.178)

Jonathan Safran Foer interviewed a PETA staff member who supports the argument according to which cutting down on animal products is a significant way of reducing global poverty:

The UN special envoy on food called it a “crime against humanity” to funnel 100 million tons of grain and corn to ethanol while almost a billion people are starving. So what kind of crime is animal agriculture, which uses 756 million tons of grain and corn per year, much more than enough to adequately feed the 1.4 billion humans who are living in dire poverty? And that 756 million tons doesn’t even include the fact that 98 percent of the 225-million-ton global soy crop is also fed to farmed animals. You’re supporting vast inefficiency and pushing up the price of food for the poorest in the world. (Foer, p.211)

In sum, as Peter Singer puts it, becoming vegetarian would “increase the amount of grain available to feed people elsewhere, reduce pollution, save water and energy, and cease contributing to the clearing of forests; moreover, since a vegetarian diet is cheaper than one based on meat dishes, they would have more money available to devote to famine relief, pollution control, or whatever social or political cause they thought most urgent.” (Singer, p.221)

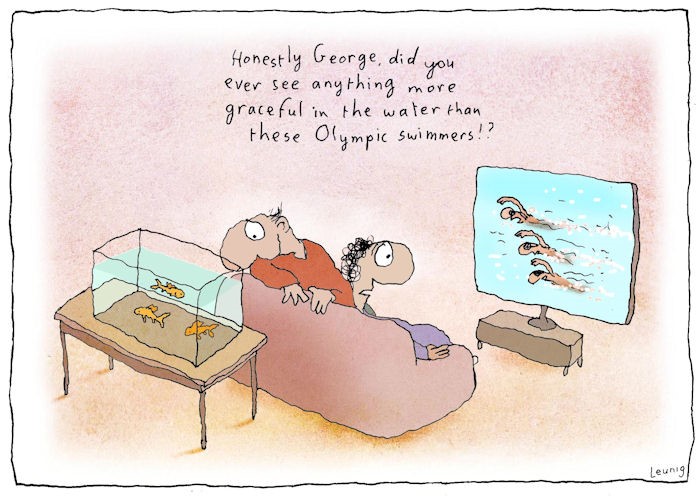

Image courtesy of Michael Leunig

1. J-B. Jeangène Vilmer points out that an inadequately fed factory-farmed chicken needs almost twice as less time as a traditionally farmed chicken to reach a certain weight, (Jean-Baptiste Jeangène Vilmer, Ethique animale (Paris: Presse Universitaires de France, 2008), p.174. All references are to this edition. Further cited in the text and shortened to author’s name and page number) while Bruce Friedrich argues that factory-farmed chickens grow 7 times as fast as chickens grew 45 years ago. (Robert Wiblin; Keiran Harris, “Bruce Friedrich Makes the Case that Inventing Outstanding Meat Replacements is the Most Effective Way to Help Animals.” 80,000 Hours. https://80000hours.org/podcast/episodes/bruce-friedrich-good-food-institute/ (accessed August 14th, 2019).). / The use of growth hormones is forbidden in Europe but allowed elsewhere. Antibiotic growth promoters in factory farming are dangerous for humans because of their toxicity (some antibiotics are carcinogenic), and because humans become resistant to antibiotics. (Jeangène Vilmer, pp.174-175)

2. Jonathan Safran Foer, Eating Animals (New York: Back Bay Books, 2010), pp.126-127. All references are to this edition. Further cited in the text and shortened to author’s name and page number.

3. otherwise known as “fecal soup” (Foer, pp.134-135) / “While a significant number of European and Canadian poultry processors employ air-chilling systems, 99 percent of US poultry producers have stayed with water-immersion systems […] water-chilling causes a dead bird to soak up […] fouled, chlorinated water. […], the new law of the land allows slightly more than 11 percent liquid absorption.” (Foer, p.135) / “According to a study published in Consumer Reports, 83% of all chicken meat (including organic and antibiotic-free brands) is infected with either campylobacter or salmonella at the time of purchase.” (Foer, p.139) / “In the United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control, tens of millions of people get sick from the bacteria in meat every single year.” (Wiblin and Harris, “Bruce Friedrich Makes the Case.”)

4. “That meat is unnecessary for physical endurance is shown by a long list of successful athletes who do not eat it.” (Peter Singer, Animal Liberation (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2009), p.180. All references are to this edition. Further cited in the text and shortened to author’s name and page number.)

5. “Excess protein cannot be stored. Some of it is excreted, and some may be converted by the body to carbohydrate, which is an expensive way to increase one’s carbohydrate intake.” (Singer, p.181)

6. Robert Wiblin, “Ending Factory Farming as Soon as Possible.” 80,000 Hours. https://80000hours.org/podcast/episodes/lewis-bollard-end-factory-farming/ (accessed July 28th, 2019).

7. Sandrine Delorme, Le cri de la carotte (Paris: Les points sur les i, 2011), p.18. / “omnivores contribute seven times the volume of greenhouse gases that vegans do.” (Foer, p.58)

8. “A pound of meat requires fifty times as much water as an equivalent quantity of wheat.” (Singer, p.167)

9. Methane – a gas that cows release by ruminating because of indigestible food – accounts for about 18% of the pollution. (LoveMEATender. Dir. Manu Coeman. AT-Production, 2011.)

10. Farming contributes to deforestation through air contamination, being responsible for 64% of ammonia emissions and involving acid rain that kills forests, and because it constantly requires space. 70% of the old Amazonian forests have been converted to pastures. (Jeangène Vilmer, p.176) / “The prodigious appetite of the affluent nations for meat means that agribusiness can pay more than those who want to preserve or restore the forest. We are, quite literally, gambling with the future of our planet – for the sake of hamburgers.” (Singer, p.169)

11. Trawling is especially “wasteful of fossil fuels, consuming more energy than it produces.” (Singer, p.173)

12. “farmed animals in the United States produce 130 times as much waste as the human population – roughly 87,000 pounds of shit per second. The polluting strength of this shit is 160 times greater than raw municipal sewage. And yet there is almost no waste-treatment infrastructure for farmed animals.” (Foer, p.174)

13. LoveMEATender. Dir. Manu Coeman. AT-Production, 2011.

14. We use land to grow food edible by humans (e.g. corn or soybeans) to feed a calf. “It takes twenty-one pounds of protein fed to a calf to produce a single pound of animal protein for humans. We get back less than 5% of what we put in.” If we use an acre of fertile land “to grow a high-protein plant food, like peas or beans. […], we will get between 300 and 500 pounds of protein from our acre,” compared to 40-55 pounds of protein, if we use this acre to grow a crop for animals to eat and then eat the animals. “[M]ost estimates conclude that plant foods yield about 10 times as much protein per acre as meat does, although […] the ratio sometimes goes as high as twenty to one.” (Singer, p.165) / Bruce Friedrich from the Good Food Institute echoes Singer’s words, taking chicken as an example: “chicken, which is the least climate change inducing meat, produces 65 times as much climate change as legumes on a per unit of energy basis.” (Wiblin and Harris, “Bruce Friedrich Makes the Case.”)

Dirty Money, Clean Conscience

Dirty Money, Clean Conscience

Factory farms are so competitive that they are unscrupulous in their relentless quest for cost minimization and production maximization1: “slaughterhouses strive to kill more animals per hour than their competitors.” (Singer, p.151)

Cost dictates every decision: “even a small differential in cost will be used to justify the most monstrous treatment […]. It is more expensive to buy carbon monoxide gas than it is to operate an electric macerator, and so they operate macerators.”2

The industry also welcomes new methods to increase profitability. “No aspect of animal raising is safe from the inroads of technology.” (Singer, p.140)

“Biotechnology, nanotechnology and artificial intelligence will soon enable humans to reshape living beings in radical new ways.”3

Image courtesy of Michael Leunig

1. Peter Singer, Animal Liberation (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2009), p.97. All references are to this edition. Further cited in the text and shortened to author’s name and page number.

2. Robert Wiblin, “Ending Factory Farming as Soon as Possible.” 80,000 Hours. https://80000hours.org/podcast/episodes/lewis-bollard-end-factory-farming/ (accessed July 28th, 2019).

3. Yuval Noah Harari, “Industrial Farming Is One of the Worst Crimes in History.” The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2015/sep/25/industrial-farming-one-worst-crimes-history-ethical-question (accessed July 30th, 2019). Courtesy of Guardian News and Media Ltd.

Filet Mignoning Reality

Filet Mignoning1 Reality

Humans sugarcoat animal cruelty through various forms of communication. Our word choices and well-thought-out use of images minimize our accountability to alleviate our guilt, and inaccurately portray animals to further widen the gap between us and them. The closed-door policy of factory farms and laboratories is telling, too. We consent, and shush. In a way, the words we don’t say harm the most.

We euphemize: hunters “harvest,” “collect,” “pick up.” Researchers “complete” or “terminate” what they call “biological materials” or “test systems,” i.e. lab animals. Slaughterhouses are “food-processing units,” “protein harvesters,” or “meat plants.” The living, sensitive nature of the slaughtered animal is repressed behind an abstract, mechanical, or agricultural terminology.2

The term “meat” itself is a cleaner way to denote an animal corpse turned into food – even more so if it is called “Filet Mignon.” (Jeangène Vilmer, pp.132-133) As Singer points out,

Buying food […] is the culmination of a long process, of which all but the end product is delicately screened from our eyes. We buy our meat and poultry in neat plastic packages. […] There is no reason to associate this package with a living, breathing, walking, suffering animal. The very words we use conceal its origins: we eat beef, not bull, steer, or cow, and pork, not pig.3

We use pejorative language. An animal isn’t only the other, it’s also an insult. The word ‘animal’ carries a negative connotation. To say that someone is an animal is to say that she is stupid or coarse. (Jeangène Vilmer, p.12) By contrast, to say that someone is humane is to say that she is kind. (Singer, p.222)

We objectify animals. For instance, the advertisements of the breeders supplying the laboratories speak of material “now available in standard or bare model” (Guinea pigs with or without hairs). (Jeangène Vilmer, p. 134) Journals such as Lab Animal advertise animals as cars, (Singer, p.38) and “grant applications to government funding agencies” list animals “as ‘supplies’ alongside test tubes and recording instruments.” (Singer, p.69)

We conceal reality through non-linguistic disguises as well, e.g. in bullfights, bright-colored banners, and dark-haired bulls to prevent the sight of blood from shocking spectators. (Jeangène Vilmer, p.133) We also embellish the truth, when depicting animals in children’s books and commercials where hens freely peck in the farmyard, calves grow up alongside their mother in the pastures, and pigs joyfully wade in the mud. (Jeangène Vilmer, p.170) Oxen smilingly queue on their way to the slaughterhouse. A lab animal is a “research collaborator” or “team player” happy to assist researchers with their work. (Jeangène Vilmer, p.135) As for the media, “[newspapers’] coverage of nonhuman animals is dominated by ‘human interest’ events like the birth of a baby gorilla at the zoo, […]; but developments in farming techniques that deprive millions of animals of freedom of movement go unreported.” (Singer, p.216)

We hide reality behind closed doors, physically denying the wrongs caused. Visits to factory farms and laboratories are restricted, if permitted.4 As Singer points out, “[r]esearch facilities are usually designed so that the public sees little of the live animals that go in, or the dead ones that come out.”5 (Singer, p.217) The same can be said of factory farms and abattoirs.

1. “Mignon” means “cute” in French.

2. Jean-Baptiste Jeangène Vilmer, Ethique animale (Paris: Presse Universitaires de France, 2008), p.132. All references are to this edition. Further cited in the text and shortened to author’s name and page number. / I once read that for 1 kilogram of honey, we need the lifetime’s work of 350 to 400 bees. It might sound silly, but this made me realize we take things for granted. We only see the end product, and forget to pay attention to all the sacrifice and efforts behind it.

3. Peter Singer, Animal Liberation (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2009), p.95. All references are to this edition. Further cited in the text and shortened to author’s name and page number. / In Intelligence and Personality, Alice Heim discusses the technical jargon animal experimenters use that doesn’t properly reflect reality and the incoherent disapproval of anthropomorphism in the scientific community: “The work on ‘animal behavior’ is always expressed in scientific, hygienic-sounding terminology, […] techniques of ‘extinction’ are used for what is in fact torturing by thirst or near starvation or electric-shocking; ‘partial reinforcement’ is the term for frustrating an animal by only occasionally fulfilling the expectations which the experimenter has aroused in the animal by previous training; […]. The cardinal sin for the experimental psychologist working in the field of ‘animal behavior’ is anthropomorphism. Yet if he did not believe in the analogue of the human being and the lower animal even he, […], would find his work largely unjustified.” (Alice Heim, Intelligence and Personality – as cited in Singer, p.51)

4. “I never heard back from […] any of the companies I wrote to. Even research organizations with paid staff find themselves consistently thwarted by industry secrecy.” (Jonathan Safran Foer, Eating Animals (New York: Back Bay Books, 2010), p.87.)

5. Labs are conscious of the discretion they need to maintain. For example, The Whole Rat Catalog suggests, referring to the Rodent Carrying Case, “Use this unobtrusive case to carry your favorite animal from one place to another without attracting attention.” Incidentally, the catalog offers electrodes and other usual material as well as i.a. Radiation Resistant Gloves and Decapitators. (Singer, p.39)

A Day at the Madhouse

A Day at the Madhouse

Some Thoughts on Anthropomorphism

As soon as I started working on this part of the blog, it was clear to me that I should try and write each of the four following texts (in italics) from the perspective of an animal to give them a voice. I’m guilty of anthropomorphism because their imagined thoughts inevitably ended up merging with my own thoughts, however hard I tried to put myself in their place.

I don’t know what it’s like to be a hen, a calf, a sow, a shrimp. So I label animals’ emotions in human language. Yet perhaps this isn’t as relevant as the message I want to convey. Could our fear of anthropomorphism impede both learning and deeper understanding of animals?

“All literary depictions of the lives of animals are made by humans, and it is likely that all our empathic imagining of the experiences of animals is shaped by our human sense of life[,]” as Martha Nussbaum points out. We assess animals’ lives “from our imperfect human point of view, but our writings can still be “powerful invitations to imagine animal suffering,” and “even those whose theoretical perspective militates against reliance on imagination do in fact consult it, […] Good imaginative writing has been crucial in motivating opposition to cruelty toward animals.”1

Our anthropomorphic projection can surely make us get things wrong, but human relationships are mysterious to us, too. Only through imaginations and literary artistry can we enter anyone else’s mind and inner life. According to Marcel Proust, when we read a novel, for instance, what we do “is what we have to do always, if we are ever to endow another shape with life. All of our ethical life involves, in this sense, an element of projection, a going beyond the facts as they are given.” (Nussbaum, Frontiers, p. 354)

Thanks to Matt Bryden for editing my drafts, and for recommending Les Murray’s lovely poem “Pigs.”

Birds

I’m in prison for a crime I didn’t commit, suffocating in the smell of droppings,2 my own and others’, burdened by the mass of my enlarged body. My body in shreds yet still somehow holding together. My fragile bones weren’t made for such excess weight. So my twig legs break.3

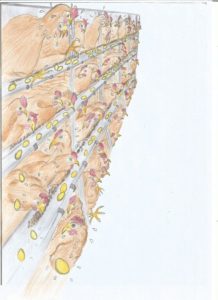

My fellow inmates look freakish with their sloppily-cut beaks with blackened ends,4 and so do I. I stare at my burnt feet. The inclined floor hurts them some more.5 There are five of us enclosed in a narrow cage,6 maybe a million in this windowless shed.

Illustration by Chloé De Wil

Today, many of the noisier7 birds are spoiling for a fight.8 The atmosphere is so hostile it makes me feel jittery and alone. They ground up my sons.9 They only kept my girls so they could lay eggs for them. My only legacy – eggs and pain. Someone comes in.

He grabs by the legs five hens10 at a time.

Illustration by Léna Toussaint

He crams them all into a rectangular transport. More limbs get broken.11

Upon arrival, taken from the truck and stacked, we wait. Hours go by.

Hung upside down on a line of hooks, we’re pushed to our death.

When life is hell, one might think death feels like a beautiful promise. It’s not true. Each bird is terror-struck as she sees the knife. If she isn’t killed on the first try, she’ll be finished off by hand.12

A spurt of blood. A brief stillness. Crimson drops fall to the concrete floor, like acid rain.

Egg farmers mess with the birds’ internal clocks by controlling “the light, the feed, and when they eat,” so the birds can lay eggs faster, at the same time, and year-round. “Turkey hens now lay 120 eggs a year and chickens lay over 300. That’s two or even three times as many as in nature.” (Foer, p.60)

Buying free-range doesn’t make much of a difference: “often, the eggs of factory-farmed chickens – […] – are labeled free-range. […] most ‘free-range’ (or ‘cage-free’) laying hens are debeaked, drugged, and cruelly slaughtered once ‘spent.’”13 (Foer, p.61) Hens in a cage-free environment are also as numerous 14 and housed “entirely indoors.” They still have to put up with “high-density operations” and “real management concerns.”15

Broilers undergo many of the same procedures as layers, among which debeaking. Debeakers generally put the infant chicks’ beaks into “guillotinelike devices with hot blades,” hastily performing the procedure at the average rate of 15 birds a minute. Sloppy cuts and severe injuries are frequent. Whatever the temperature of the blade, the bird is left with either blisters in the mouth or a developing growth on the mandible, or with burnt nostrils. These injuries cause acute and long-term pain. Even when debeakers do the operation correctly, the bird suffers greatly as the knife cuts through highly sensitive, thin layer of tissue. (Singer, pp.101-102)

The artificially ventilated broiler sheds have windowless walls, and the ammonia from the birds’ waste fills the air.16 Should there be a mechanical failure, they soon suffocate. They might also suffocate by “piling” on top of one another. The intrusive environment makes them edgy and, “they may panic at a sudden disturbance and flee to one corner of the shed” to feel safer, forming a heap of bodies. (Singer, p.103)

Like laying hens, broiler chickens sorely lack space – even when they don’t pile on top of each other: “A producer of broilers gets a load of 10,000, 50,000, or more day-old chicks from the hatcheries, and puts them into a long, windowless shed.” (Singer, p.98)

The stuffy housing conditions confuse and stress factory-farmed chickens so much that they behave in ways they would never behave in their natural environment. The chickens fight because the overcrowding prevents them from establishing a stable social order: “the stress of crowding and the absence of natural outlets for the birds’ energies lead to outbreaks of fighting, with birds pecking at each other’s feathers and sometimes killing and eating one another. […] Feather-pecking and cannibalism […] are not natural vices, […] Chickens are highly social animals, and in the farmyard they develop a hierarchy, sometimes called a ‘pecking order.’” (Singer, pp.99-100)

Broiler chickens’ environment is also closely controlled for them to be more productive on less feed:

Food and water are fed automatically from hoppers suspended from the roof. […], there may be bright light twenty-four hours a day for the first week or two, to encourage the chicks to gain weight quickly; then the lights may be dimmed slightly and made to go off and on every two hours in the belief that the chickens are readier to eat after a period of sleep; finally there comes a point, around six weeks of age, when the birds have grown so much that they are becoming crowded,17 and the lights will then be made very dim at all times. (Singer, p.99)

The chickens grow at such speed that they become crippled and deformed, so the producers kill some of them. (Singer, p.104) The genetics that broilers are born with have been engineered for them to grow as quickly as possible with as little food as possible, which means that the birds grow up to 6 times faster than they did in the 1950s, while the birds’ systems can’t keep up with that. Thus, the birds become lame later in the growing period, have respiratory or heart problems.18

Jonathan Safran Foer visited with a former factory farm employee “the kind of farm that produces roughly 99 percent of the animals consumed in America.” From the enormous fans, to the row of gas masks on the wall, to the chicks sleeping beneath the heat lamps – substitutes for the warmth their mothers would have given them, Foer describes in Eating Animals the “mathematical orchestration” and “technological symphony” of the facility, and suggests that “[b]esides the animals themselves, there is no hint of anything you might call ‘natural.’” (Foer, p.86-88)

Not only are the units efficiently calibrated, but the entire process is calculated so that a manic work pace is maintained, even if it means carelessly handling the birds during both the trip to the slaughterhouse and the slaughter itself19: a worker usually grabs by the legs five birds in each hand,20 and packs them into transport crates piled on the back of a truck that will drive them to a plant sometimes hundreds of miles away. At the plant the birds are “stacked, still in crates, to await their turn. That may take several hours, during which time they remain without food and water.” (Singer, p.105) Finally, “more workers sling the birds, to hang upside down by their ankles in metal shackles, onto a moving conveyer system” that “drags the birds through an electrified water bath.”21 (Foer, pp.132-133)

In pain and terrified, the birds will often defecate, and “feces […] end up in the tanks.” Filled with pathogens inhaled or absorbed through their skin, the birds have their heads and legs removed, and “machines open them with a vertical incision and remove their guts. Contamination often occurs here, as the high-speed machines commonly rip open intestines, releasing feces into the birds’ body cavities.” (Foer, pp.133-134)

The inspector has about two seconds to examine each of the 25,000 birds s/he will see in a day.22 The bird is then cooled amid thousands of other birds in a “massive refrigerated tank of water.” (Foer, p.134)

As if that weren’t enough, gratuitous violence is widespread, adding to the profoundly sick system. At the facilities of two KFC23 “Suppliers of the Year,” workers were found “tearing the heads off live birds, spitting tobacco into their eyes, spray-painting their faces, and violently stomping on them”24 (Foer, p.67) and “kick[ing], stomp[ing] on, slamm[ing] into walls” fully conscious birds, spitting tobacco in their eyes, literally squeezing “the shit […] out of them,” and ripping their beaks off. At yet another facility, employees were witnessed “urinat[ing] in the live-hang area […], and let[ing] shoddy automated slaughter equipment that cut birds’ bodies rather than their necks go unrepaired indefinitely.” (Foer, p.182)

A few words on FOIE GRAS

Foie gras is a sick, fatty liver whose weight has been multiplied by 10 or 12: it changes from 60 to 500-600 g in the duck and from 80 g to 1 kg in the goose. Force-feeding consists in pushing down a 20 to 30cm-long pipe from the throat to the stomach of the animal, administering her a large quantity of highly calorific and imbalanced food. The procedure lasts 2 to 3 seconds for modern force-feeding which uses a pneumatic pump, and can force-feed over 350 ducks per hour. It takes place twice a day. For a man of 70 kg, that would equate to force-feeding him 2x7kg (i.e. a tenth of his weight) of pasta in a few seconds. Force-feeding causes throat lesions as well as pain, stress, traumatic shock, diarrhea, gasps. The deformation of the enlarged liver which reaches 10 times its normal volume when the force-feeding is over makes breathing and moving difficult because the animal’s air sacs are compressed by an organ that crushes its surroundings, and the center of gravity has been moved. The animal’s liver has a level of hepatic steatosis that would kill the animal if she kept being force-fed for only 3 additional days. (Jeangène Vilmer, pp.179-180)

Cattle

It’s dark in this small box of sorts.25 I can vaguely discern the wooden slats under my hooves.26 How come I feel so frail despite my heaviness?27 I want to clean my coat, but my chained neck always gets in the way.28 I dream of a comfortable straw bed.29 I dream of seeing my mom again, of having her by my side. I could hear her call at the beginning, but she fell silent.30

Illustration by Léna Toussaint

I caught a glimpse of sunlight once. It was beautiful and scary. The place bathed in warmth for a split second. It was the closest thing to an embrace I had ever received. The sunrays drawing me to them, like loving arms.

Then, one day, I saw it again. Except now it was scary. They opened the door, and took me out.

Illustration by Chloé De Wil

It’s been hours and hours. The overpowering heat and the weight of bodies crushing me make me feel dizzy, as if my scraped knees are about to give way. That’s all I remember before I collapse: the jammed foul-smelling truck, the sick and dead bodies, the foolish hope I held on to for one brief moment.

When they finally unload us, grabbing me, one of the two says, ‘This one’s unfit, too,’ and tosses me aside31 like a rag doll.

The calves may be trucked hundreds of miles away from their birth place, and the journey to the slaughterhouse is a “combination of fear, travel sickness, thirst, near-starvation, exhaustion, and possibly severe chill”:

cattle often spend up to forty-eight or even seventy-two hours inside a truck without being unloaded. […] After one or two days in the truck without food or water they are desperately thirsty and hungry. Normally cattle eat frequently throughout the day; their special stomachs require a constant intake of food […]. If the journey is in winter, subzero winds can result in severe chill; in summer the heat and sun may add to the dehydration […] In the case of young calves who may have gone through the stress of weaning and castration only a few days earlier, the effect is still worse. (Singer, p.148)

The calves usually lose weight (“shrinkage”) or develop a form of pneumonia (“shipping fever”). Others won’t even reach the slaughterhouse alive or will arrive severely injured:

Animals who die in transit […] freeze to death in winter and collapse from thirst and heat exhaustion in summer. They die lying unattended in stockyards, from injuries sustained in falling off a slippery loading ramp. They suffocate when other animals pile on top of them in overcrowded, badly loaded trucks. They die from thirst or starve when careless stockmen forget to give them food or water. And they die from the shear stress of the whole terrifying experience. (Singer, p.149)

Regarding the dairy cow, her life is that of an ongoing cycle: insemination, parturition, having the calf taken away, starting again. Her udders are constantly full, which equates to a load of 50 kg. Through unnatural methods (genetic manipulation, antibiotics, hormones), production is maximized (6,000 to 12,000 L of milk per year, i.e. 10 times more than 50 years ago). This causes hypertrophy of the pelvis and teats and at the same time pain, limps, and infections. (Jeangène Vilmer, pp.172-173)

Intensively raised dairy cows live in a controlled environment where “temperatures are adjusted to maximize milk yield, and lighting is artificially set.” As soon as the cow’s production cycle starts, she is repeatedly milked, and “[u]sually this intense cycle of pregnancy and hyperlactation can last only about 5 years, after which the ‘spent’ cow is sent to slaughter.” (Singer, p.137)

In terms of diet, “producers feed cows high-energy concentrates such as soybeans, fish meal, brewing byproducts, and even poultry manure[,]” which the cow’s digestive system can’t process well. Later, [b]ecause her capacity to produce surpluses her ability to metabolize her feed, the cow begins to break down and use her own body tissues.” (Singer, p.137)

Beef cattle’s stomachs are also unsuitable for the food they receive in feedlots. In an attempt to get more fiber, they “lick their own and each other’s coats.” However, “[t]he large amount of hair taken into the rumen may cause abscesses.” (Singer, p.140)

As is the case for other intensively confined animals, “the barren, unchanging environment” bores the beef cattle. They are also dangerously exposed to harsh climatic conditions. (Singer, p.140)

Virtually all beef producers dehorn their cattle to make space,32 castrate them (generally without pain relief) for “fear that the male hormones will cause a taint to develop in the flesh[,]” and because it is easier to handle castrated animals, (Singer, p.145) and brand them to prevent straying, rustling33 and facilitate record-keeping, which is torture for cattle.34

Even traditional systems seem to cut off their cattle’s horns “with hot irons or caustic pastes” and castrate the animals who all spend their last months on a poor diet on an inadequate feedlot. (Foer, p.224) They also “involve the separation of mother and young at an early age,” which is painful to both, (Singer, p.146) as well as “breaking up social groups, branding, transportation to the slaughterhouse, and finally slaughter itself.” (Singer, p.160)

In an 80,000 Hours podcast, scientist Marie Gibbons tells us about her own experiences working on “local, family-owned, pasture-raised” farms, some of which animal welfare approved:

we were still cutting horns off of baby goats and literally ripping testicles out of baby pigs and cows. […] the testicles do not get cut out. They are ripped out because if you were to cut off the testicles, then the animal would most likely bleed out. […] a lot of these procedures are not performed by vets, not performed with pain medication. […] if things like that were going on in these pristine, happy farms, then what’s going on in the factory farms?35

Beef cattle are adolescent at the time of slaughter36 and, as is the case for calves, they find the trip to the slaughterhouse stressful.37

A typical cattle slaughter:

1) chute –> 2) “knocker” –> 3) “shackler” –> 4) “sticker” –> 5) “bleed rail” –> 6) “head-skinner” –> 7) “leggers”

1-2) The cow is led through a chute to the “knocker” who “presses a large pneumatic gun between the cow’s eyes.” A steel bolt shoots into her skull, sometimes only dazing the animal who wakes up while going down the processing line. The crudely punctured animal may be left conscious on purpose. (Foer, pp. 229-230) Sometimes the knocker doesn’t stun the animal at all.38 (Foer, p. 231)

3) the “shackler” shackles one of the cow’s rear legs and lifts the animal (Foer, p. 232)

4-5) The dangling animal is mechanically moved to a “sticker,” “who cuts the carotid arteries and a jugular vein in the neck[,]” and then to a “bleed rail” and “drained of blood for several minutes.” (Foer, p. 232)

6) The cow turned into a carcass is moved to a “head-skinner” who peels off her skin. The animal is often still conscious when the skinner slices the side of her head, and kicks. So the skinners shove a knife into the back of her head. (Foer, p. 233)

7) the “leggers” “cut off the lower portions of the animal’s legs. […] The animal then proceeds to be completely skinned, eviscerated, and cut in half, at which point it finally looks like the stereotyped image of beef – hanging in freezers with eerie stillness.” (Foer, p. 233)

Pigs

I’m a machine for making piglets. This is my second pregnancy.39 I feel so uncomfortable. I want to turn around, but can’t. I’m immobilized, half-lying on one tingling side of my body in a tiny crate.40

The first time he tried to lock me in, I struggled, but my tormentor would have none of it. He kicked my flank as hard as he could. I saw his red face and the bulging veins in his forehead and neck. Then I took another blow. Another. He hit my snout until it bled and knocked me down to the bloodstained floor. I was inside the stall. His strenuous efforts had paid off. He wiped his hands clean with his shirt, as if to say, over and done with. Triumphant, he spat on the floor.

I’ve been still ever since (I can hardly move anyway),41 but he routinely beats me with his rod42 so the blood doesn’t dry. It hurts.

It’s a vicious cycle: insemination, gestation, farrowing,43 separation, insemination.44 Get pregnant, gestate, give birth, have your babies stolen.45 Repeat. Time goes by so terribly slowly.46 … gestate, give birth, have your babies stolen. Repeat. Repeat.

The sores all over my body won’t heal.47 I can feel them. I’m struggling to get air.48 I’m exhausted. And lonely. I’m carrying babies, but I don’t feel like a living thing. I’m all wounds. A dry throat and hunger pangs.49

Now I hear footsteps and voices. I am terrified.50 The shoes hitting the concrete are cruel to my ears. Holding my breath, I am the word ‘fear’ trying to erase itself as they approach.

A piglet’s daily life is just as hellish, from day one. Many are born with congenital diseases.51 Even the newborns without defects “endure a barrage of bodily insults. Within the first forty-eight hours their tails and ‘needle teeth,’ […], are cut off without any pain relief in an attempt to minimize the wounds pigs inflict upon one another while competing for their mother’s teats in factory settings where pathological tail biting is common.”52 (Foer, p.186) Another way to prevent the piglets from enacting “social vices”53 is to keep the environment lethargy-inducing, i.e. warm and dark.

Within days of birth, the workers often inject the piglets with iron as their mother’s rapid growth and intensive breeding is likely to have made their milk deficient, (Foer, p. 186) and castrate the male pigs without anesthesia.54 Their drug food makes them gain 100 kg in 20 weeks. (Jeangène Vilmer, p. 172) As Lewis Bollard points out, “[castration] is standard practice for virtually all male piglets, globally. We know that that is a process that causes minutes of intense pain as measured by stress responses and that they’re still feeling some degree of pain … days, weeks later.”55

The pigs may also have their ears partially cut out to facilitate identification. “By the time farmers begin weaning them, 9 to 15 percent of the piglets will have died.” (Foer, p. 187)

Factory-farmed piglets are given solids56 at about 15 days57 so they can reach market weight as soon as possible.58 The workers then force them into thick-wire cages “stacked one on top of the other, and feces and urine fall from higher cages onto the animals below,” before transferring them to cramped pens. (Foer, p. 187) Slow-growing pigs “are a drain on resources […]. Picked up by their hind legs, they are swung and then bashed headfirst onto the concrete floor.”59

Just like their mothers, the piglets spend their lives confined. In this way, not only can they be separated from their mothers earlier but, because they burn fewer calories, the meat is also more tender for the consumers’ enjoyment and less feed is needed, which satisfies factory farms’ “desire for faster gains on less feed.” (Singer, p. 125)

To keep the pigs alive under adverse circumstances,60 the factory farm employees give them dozens of pharmaceuticals (antibiotics, hormones, vaccines, anti-inflammatory drugs, etc.). Sometimes the needles break and remain in the muscle. (Jeangène Vilmer, p. 172) However, the medication doesn’t relieve stress,61 or cure “learned helplessness” or even insanity.62

Even if factory farm workers did care about sick animals, it would be difficult to spot them: “lame and diseased animals are almost impossible to identify when no animals are allowed to move.” (Foer, p. 184)

When it comes to the slaughter itself, while a huge machine holds the pig in place, a “knocker” discharges a “shocker”63 on top of the animal’s head. (Foer, p. 154) When the shocker fails, a bolt knocker serves as backup, pressing steel into the animal’s skull. (Foer, p. 155) Done with one pig, the knocker then goes get another pig, using a paddle with a rattler. (Foer, p. 161)

In factory farms, the setup is such that inspectors can’t properly monitor the kill area from their stations or detect abnormalities in the carcasses flashing by. (Foer, p. 155)

Apart from the atrocious routine slaughter practices, perversion is all too common. Videotaped instances showed employees at an industrial pig-breeding facility “administering daily beatings, bludgeoning pregnant sows with a wrench, and ramming an iron pole a foot deep into mother pigs’ rectums and vaginas. […] saw[ing] off pigs’ legs and skinn[ing] them while they were still conscious.”64 (Foer, pp. 181-182)

Sea Animals

I’m what’s left of a shrimp. We’ve been dragged with pebbles and other marine debris, for what feels like forever. Gashes cover my now skinless body.65 The water so foul and crowded I can barely breathe.

It seems we’ve reached our destination. They haul us on deck,66 decompression bursting our bladders. I see eyes popping out of their sockets and mouths throwing up internal organs. While we’re writhing in agony, they select some of us, using sharp tools.67

They electrocute, bash, bleed the chosen ones to death. They immerse them in a filthy water tank, then slice their gills.68 I wait my turn, still suffocating. Lifted from the blue immensity I once called home.

Illustrations by Chloé de Wil

Pisciculture raises the same issues as factory farming, namely overcrowding, aggressive behaviors, emergence and proliferation of diseases, infections and injuries, use of chemicals, antibiotics and toxic treatments, poisoned environment. (Jeangène Vilmer, p. 255) Like the meat industry, the fish industry neglects the animals’ health for practical reasons. The hygienic conditions are so appalling that sea lice thrive, and “create open lesions and sometimes eat down to the bones on a fish’s face – […]. A single salmon farm generates swarming clouds of sea lice in numbers thirty thousand times higher than naturally occur. The fish that survive these conditions […] are likely to be starved for seven to ten days to diminish their bodily waste during transport to slaughter.” (Foer, p. 190)

As is the case with the meat industry again, waste is another major issue. Globally, 1/3 of industrially caught fish are used to make animal flour and oil. Animal flour, obtained by crushing fishes together, is fed to farmed fish and shrimp. To produce 1 kg of farmed fish, it takes 2 to 6 kg of caught fish. Besides, every year, we unintentionally kill over a million fishes, wasting 8-10 kg of fish for 1 kg of shrimp. At least 1/5 of world catches are waste. (Jeangène Vilmer, pp. 253-254) And, because “the most desired fish […] are usually top-of-the-food-chain carnivores like tuna and salmon, we eliminate predators and cause a short-lived boom of the species one notch lower on the food chain. We then fish that species into oblivion and move an order lower.” (Foer, p. 192)

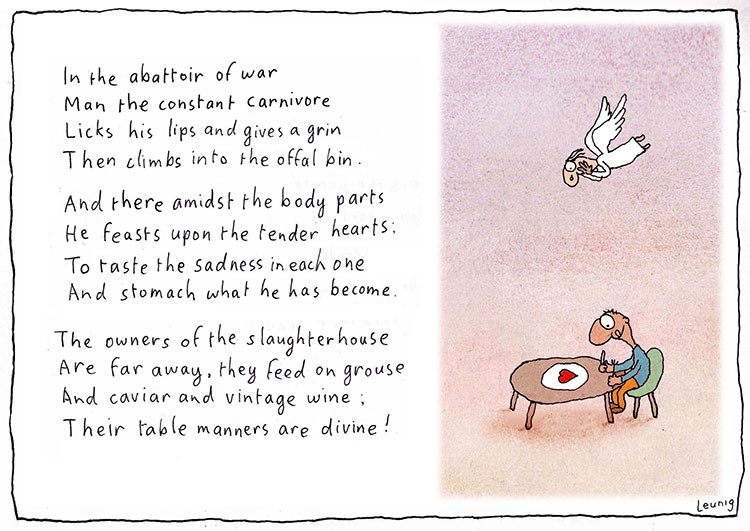

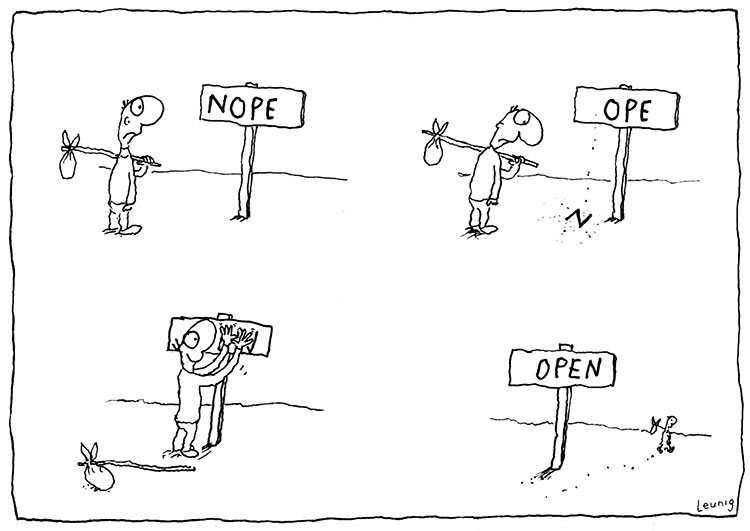

Image courtesy of Michael Leunig

Under water and on land, we transform living beings, who are every bit as worthy as we are, into production machines. We turn animals’ genetics and immune systems upside down, and drug them to half-fix our mistakes. We incarcerate them, we deform, bruise, cripple them, and have them multiply to later eat them, and start over.

There’s nothing natural about mass producing meat or fish. By housing animals in a setting so foreign to them under such unnatural conditions, we prevent them from engaging in instinctive behaviors, and from enjoying their lives in this world that is as much theirs as it is ours. It is an assault on both their senses and their dignity.

As shown, not only do factory farm workers often botch their tasks, but many are also intentionally cruel to the animals. When Temple Grandin started surveying slaughterhouses, she witnessed “deliberate acts of cruelty occurring on a regular basis” at 32 percent of the US factories she visited. Those were announced audits “that gave the slaughterhouse time to clean up the worst problems. What about cruelties that weren’t witnessed? […] And what about the vast majority of plants that don’t open their doors to audits in the first place?”69 (Foer, pp. 255-256)

As consumers we trade off health for profitability, and animal welfare for taste preferences or even for snobbism (e.g. in the case of veal or lean pig meat). We subject animals to inexpressible horrors for a club sandwich absent-mindedly gobbled up on the way to work.

Photo by Annie Spratt on Unsplash

1. Martha C. Nussbaum, Frontiers of Justice: Disability. Nationality. Species Membership (Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2007), pp. 353-354. All references are to this edition. Further cited in the text and shortened to: Nussbaum, Frontiers, (page number).

2. The ammonia of the birds’ droppings that cover the soil gradually burns their legs and abdomen, while it poisons the air. (Jean-Baptiste Jeangène Vilmer, Ethique animale (Paris: Presse Universitaires de France, 2008), p. 171. All references are to this edition. Further cited in the text and shortened to author’s name and page number).

3. In addition to bone fractures, laying hens suffer from osteoporosis, liver diseases, beak ulcers, bronchitis, cancerous tumors, and heart attacks. At the end of their short life, 1/3 of laying hens will have broken legs. The condition of their flesh being often pathetic, they end up as ravioli stuffing or hen broth. (Jeangène Vilmer, p. 172)

4. Machines equipped with a heating blade slice the 1- to 10-day-old pullets’ beaks. This debeaking to “correct” a behavioral disorder itself due to crowding, entails suffering, contamination, and sometimes death. (Jeangène Vilmer, pp. 171-172) / Because they live longer than broilers, layers often go through this operation twice. (Peter Singer, Animal Liberation (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2009), p. 107. All references are to this edition. Further cited in the text and shortened to author’s name and page number).