Irrational Thoughts

My father’s feet. That’s about the first image that came to mind as I sat down to write my grief story.

My dad is eating at the coffee table in our living room, crouching. The sight of his position troubles the sensitive child I am: the weight of his body is resting on his toes. I think that it might hurt my dad, that he’d be more comfortable, if the entire soles of his feet – rather than just the fore parts – touched the floor.

This led to another memory, another instance of illogical thinking. We’ve gathered beside my dad’s corpse. He doesn’t look like himself. I try to put a flower in his stiff hands, as I’m told to, but it isn’t stable. I don’t dare to sink the flower deeper into his hands for fear of hurting my dad. Perhaps I’m afraid his hands will give way, and break. It doesn’t make sense to try to spare my dad’s now unfeeling body a stem’s light tingle. Still I can’t see past the fact that here lies my dad – my sick dad I would bring meal trays to, my dad whose feet I meant to protect from harm.

I saw my father lifeless. Then they put him in a tower of sorts, and set it on fire. That he was really gone should have registered. And yet I caught myself thinking irrationally again and again. My eyes would search for him amid a crowd, thinking that among all the strangers’ faces I might find his. He would often be away for work, and it didn’t seem impossible this was just a longer absence. It did seem absurd yet possible that he had faked his death to rebuild his life and start over. “He looks like dad,” my sister once said, looking at the man in the rearview mirror. I wasn’t the only one to see him reappear for a split second at times, or to wish he would.

Somehow, I didn’t regard my father’s death as something permanent. I’m not alone in having taken refuge in “magical thinking.” After John Gregory Dunne’s death, Joan Didion recalls in The Year of Magical Thinking, “I was thinking as small children think, as if my thoughts or wishes had the power to reverse the narrative.”1 Because she “believed that given the right circumstances he would come back,” (Didion, p.150) Didion couldn’t bring herself to give away her husband’s belongings, such as his clothes or the shoes he would need. As she writes, “‘Bringing him back’ had been through those months my hidden focus, a magic trick,” (Didion, p.44) and “how could he come back if he had no shoes?” (Didion, p.41)

Reconstructing the Collision

I remember scraps of the conversation the evening before my father’s departure to his hometown where he was to die, him mentioning the kidney transplant, life being no bed of roses. I remember him scribbling and writing Lao letters. “What does this mean,” I asked. He said it was his name. What became of this sheet of paper, I wonder. I’d do anything to have another look at it, to hold it in my hands. Did he know it was his last trip? Was he scared? Now I see his scribbles as his way of leaving a trace – like people carving on walls or trees, “I was here.”

The grieving are left with crumbs of comfort, and try to collect every single one of them. These relics of sorts are small consolations, but consolations nonetheless. Any seemingly insignificant detail becomes precious. Discovering her husband modified a file the day of his death, Joan Didion wonders “[w]hat it was he added or amended and saved at 1:08 p.m. that afternoon.” (Didion, p.187) In her TED talk, Nora McInerny tells us how, after they emptied the bag of her husband’s ashes and spread them in his favorite river, she licked her hands clean, sort of feeding herself on the ashes stuck to her fingers: “I could have just put my hands in the water and rinsed them, but instead, I licked my hands clean, because I was so afraid of losing more than I had already lost, and I was so desperate to make sure that he would always be a part of me.”2

Yet the traces left behind can appear to carry extra meaning, leading to even more questions and a labyrinth of reflections. Considering the faint strokes of a pencil, Didion asks herself, “Why would he use a pencil that barely left a mark. When did he begin seeing himself as dead?” (Didion, p.147) The author is also “stricken” when she realizes that, by absentmindedly turning the pages of the dictionary her husband had left open, she lost the page he had last seen: “what word had he last looked up, what had he been thinking? By turning the pages had I lost the message?” (Didion p.153)

Perhaps grief survivors think discreet warning signs might have heralded their loved ones’ death. As Didion points out, “[s]urvivors look back and see omens, messages they missed.” (Didion, p.152) Perhaps they think they may have prevented it, had they paid attention or said the right words in time. “If I had said [that one small thing that made him happy] in time would it have worked?” (Didion, p.146) Towards the end of The Year of Magical Thinking, Didion realizes what she’s been trying to do since the day following John’s death: “I had been trying to reverse time, run the film backward […] substitute an alternate reel. Now I was trying only to reconstruct the collision, the collapse of the dead star.” (Didion, p.184)

We know nothing, no trick, could have changed the outcome. But still, we cling to little things to understand why and how someone who lived with us, someone who an instant ago breathed, brushed their teeth, walked the dog, ran errands, cooked, worked, made plans, joked, cried, gave, talked, learned, dreamed, thought, felt… can just cease to exist.

And so here come the what ifs and the whys. Anyone who’s ever lost someone s/he loves is probably familiar with this thought pattern. When my father died, I asked myself – I still do sometimes – torturous questions, such as “What if we hadn’t let him leave in that state and he had stayed here until he gets healthier?”, “What if he had been taken to the hospital a minute earlier?” or “What if the doctors hadn’t taken proper care of him?” Similar questions haunt Sandra M. Gilbert, who explores how the personal, the cultural, and the literary intersect in Death’s Door: Modern Dying and the Ways We Grieve: “What if the surgeon’s knife hadn’t slipped (as perhaps it did), I ask myself on the most perilously speculative days, what if the residents had been more competent?”3

More often than not though, I’ve felt guilt-ridden, thinking myself responsible for rather than victimized by my father’s death. When you can’t find an external culprit, you turn against yourself. “I realize how open we are to the persistent message that we can avert death. And to its punitive correlative, the message that if death catches us we have only ourselves to blame.” (Didion, p.206) Some survivors don’t wonder ‘why me’ or ‘why us,’ believing instead that they deserve such punishment and the suffering that ensues. In Death’s Door, Gilbert relates that she was plagued by self-blame, when her husband died: “besides feeling foolish and monstrous, I think I feared that I was guilty. Like the suffering animal about whom Browning’s Childe Roland remarks that he ‘must be wicked to deserve such pain,’ I had somehow done something undefined but nevertheless opprobrious, for which I was being punished.” (Gilbert, pp.259-260)

Photo by Cristian Newman on Unsplash

Not only do we blame ourselves for failing to avert death itself but also we blame ourselves for our “deficiencies in love” – real or imagined – that restrained us from showing the person who’s gone how much we cared about him or her when s/he was still alive: “I blamed myself still, for all the inattentiveness and the anger and all the deficiencies in love that I could find in my history with her, and some that I may possibly have invented.”4

The Tiny, Heartbreaking Commonplace

Details become salient not only because we seek to understand the cause of our loved one’s death and how it happened, by looking back on the immediate days or hours preceding it and examining them. I think that among the elusive memories it’s the details that stand out, the mundane, the particular, because they permeated virtually all aspects of life with that special person.

‘Pervasive’ comes to mind, when I seek to describe grief. When someone you love dies, the void is palpable indeed because an individual of enormous importance is gone and, together with them, all the moments shared that now seem fleeting and irreplaceable. In A Grief Observed, C.S. Lewis reminisces about the days with his wife Helen. He writes about all the things he wants back and measures the immensity of his loss: “The old life, the jokes, the drinks, the arguments, the lovemaking, the tiny, heartbreaking commonplace. […], to say ‘H. is dead,’ is to say ‘All that is gone.’”5

However paradoxical it may sound, ‘foggy’ and ‘blurry’ are yet other words I associate with grief. I wonder at times, did it actually happen that way? Was my father really as I remember him? It’s as if the event had knocked me on the head somehow. C.S. Lewis can’t see Helen’s face distinctly in his imagination, either. “We have seen the faces of those we know best so variously, from so many angles, in so many lights, with so many expressions – [….] – that all the impressions crowd into our memory together and cancel out in a mere blur.” (Lewis, p.15)

And yet again it’s the details that resurface, taking center stage – that time my sister and I couldn’t stop laughing at my father’s pronunciation of the word ‘oiseaux,’ that time the kiosk owner let my father buy me candy at a lesser price but I asked him later with the amusing seriousness mature children show, “did you bring the rest of the money to the kiosk?” (he did), that time I distracted my dad from his work by spraying perfume all over my stylish cuddly toy and marking it with my dad’s red stamp and he patiently put up with it, the rest stops during our road trips, the magic formula we’d made up for him to come back home sooner…

14 years after my father’s death, I composed a poem listing all the details through which I remember him. My father was an original, and I wanted to sort of immortalize him and make sure that I recollect what we shared and all the things that made him singular. Despite my first-hand experience with grief, I didn’t have any revolutionary metaphysical truth to reveal or words of wisdom to offer. I didn’t think this poem could matter to anyone but me. And yet perhaps it wasn’t worthless. Again, turning to literature, I realized I wasn’t alone. Other people have written about the quotidian to approach something earth-shattering, indeed life-changing: death.

In Elaine Feinstein’s elegy “Dad,” her dad’s hat is central because he’s left his imprint on it. Seamus Heaney’s “Clearances – 3” is about the poet and his mother peeling tomatoes on a Sunday. To quote Gilbert:

Inventorying the possessions of the dead as if to claim that, as Lowell implies in Life Studies, those who have “passed away” from the material world can be known only by the material goods they left behind, late-twentieth-century poets assemble list after list of the things that metonymically stand in for those who have died. The very stuff of domesticity – […] – frequently forms the basic substance of memory. (Gilbert, p.431)

In Philip Roth’s heartfelt and tender memoir Patrimony: A True Story about the author’s relationship with his dying father, Roth tells himself, “I must remember […] everything accurately so that when he is gone I can re-create the father who created me.”6

Martha Nussbaum notes that “it is often tiny details of the dense picture of the person one loves that become the focus for grief, that seem to symbolize or encapsulate that person’s wonderfulness or salience. […] the many details one notices about a person also enrich the love we feel.” (Nussbaum, pp.65-66) A person’s wonderfulness lies in the details. It’s somewhat of a vicious cycle though: the more we love, the more we remember, and the more we remember, the more we love. Because the memories can bring excruciating pain, it’s natural to sometimes wish we could forget. And yet, why want to lessen love, impoverish it when you can enrich it? I believe details are worth holding on to, even if it means some days will be tougher to navigate.

Losing Several People in One

In high school I met with a counselor to explore career choices but instead we ended up talking about my late father. Part of me resented her for deviating from the subject, part of me welcomed this chance: I did, indeed, want to talk about my father. I told her how at bedtime he’d escort me to my room. My siblings and I were scared of the basement and first floor rooms of the house, and my vivid imagination would only add to the eerie atmosphere we had created. I told her that, when we had bad grades, we’d ask him to sign the results of our classroom tests, when mom wasn’t around. As a laid-back parent he’d say, “you’ll do better next time” or “you know it’s bad, right?” The counselor said I didn’t only lose my father. I lost my best friend, too.

I left her office with tears in my eyes. What I felt was sadness but also something akin to relief: now I knew why the void felt so immense. When we lose someone we truly love with our whole heart, we grieve several people in one. My dad wasn’t just a father: he represented many different people to me. As Nussbaum explains in Upheavals of Thought, “in my grief I endow my mother with (at least) three different roles: as a person of intrinsic worth in her own right; as my mother, and as an important constituent of my life’s goals and plans; and as a mother, that is, a type of person that it would be good for every human being who has one to cherish.” (Nussbaum, pp.52-53)

— A note about the death of a parent in particular. Referring to the death of a parent, Nussbaum writes, “it is that death that seems the most final and irrevocable, being the death of a part of one’s history that has great length and depth, to which no replacement can bear anything like the same relation.” (Nussbaum, p.68)

I lost my dad when I was a child, but I can only imagine that, when you’re an adult and one of your parents is suffering, sick or dying, it brings you back to your childhood, and it’s a vulnerable place to find yourself in. The pain can be greater when one loses a spouse, a friend, or a child, of course. Many of us are ambivalent about our relationship with our parents. Yet it appears one misses in an especially “primitive” way the person who accompanied one through the early years of life. Still according to Nussbaum,

One misses in a primitive way what held one and gave one comfort: even when one fastens on particular details, […], they are complex eudaimonistic symbols of comfort and support. […], when some triggering perception reminds me of my mother’s fall coat, or her way of saying “Martha,” or her hairstyle – these memories are painful because they are reminders of the absence of comfort and love. (Nussbaum, p.85)

Joan Didion’s transcription of a friend’s letter passage echoes this idea: the death of a parent “despite our preparation, indeed, despite our age, dislodges things deep in us, sets off reactions that surprise us and that may cut free memories and feelings that we had thought gone to ground long ago.” (Didion, p.27)

Illustration by Jayde Perkin

My Body, an Empty House

The death of someone close to us leads us to think about (and fear) the vulnerability of our bodies and our own mortality. In the case of the death of a parent, it may feel like “helplessly standing on the edge of an abyss – and that sense of helplessness is surely colored by the sense that one is now the generation next to die.” (Nussbaum, p.7)

As for people who’ve lost a partner, for instance, they realize more fully the importance of love and companionship, of having somebody to support you, to catch you when you fall. Getting through each day, each night, induces anxiety: left alone, they feel like they need to find ways to ensure their own safety:

What if I fell? What would break, who would see the blood streaming down my leg, who would get the taxi, who would be with me in the emergency room? Who would be with me once I came home? […] I started leaving lights on through the night. If the house was dark I could not get up to make a note or look for a book or check to make sure I had turned off the stove. If the house was dark I would lie there immobilized, entertaining visions of household peril, the books that could slide from the shelf and knock me down. (Didion, p.167)

Many survivors will tell you a part of them did die when their loved one died. I find that losing someone you love feels like an amputation, like losing a limb. It can even feel like losing your entire self: “when we mourn our losses we also mourn, for better or for worse, ourselves. As we were. As we are no longer. As we will one day not be at all.” (Didion, p.198)

The truth is, a beloved’s death does change the people who remain, and it’s natural to resist this change: “as one reweaves the fabric of one’s life after a loss, and as the thoughts around which one has defined one’s aims and aspirations change tense, one becomes to that extent a different person. This explains why the shift itself does not take place without a struggle: for it is a loss of self, and the self sees forgetfulness and calm as threatening to its very being.” (Nussbaum, p.83)

We can’t escape grief as it’s not local. Rather, it’s like an unavoidable place: the emptiness and anguish are most sharply felt within oneself. “Her absence is no more emphatic in those places than anywhere else. It’s not local at all. […] [my own body]’s like an empty house.” (Lewis, p.12)

A Mixed Bag of Emotions

It seems hardly possible to prepare for a loved one’s death. It often comes as a shock, even if the person was sick, because of “hopes […] forced upon us, by false diagnoses, by X-ray photographs, by strange remissions, by one temporary recovery.” (Lewis, p.27) Anyone who has ever cared for a loved one with a serious illness can, I believe, recognize those false hopes that are not the product of wishful thinking, but rather come from encouragement outside of yourself.

Photo by Başar Doğan on Unsplash

Joan Didion touches on how the ordinary nature of the circumstances preceding someone’s death prevent us from believing the unthinkable has really happened: “It was in fact the ordinary nature of everything preceding the event that prevented me from truly believing it had happened, absorbing it, incorporating it, getting past it. […] there was nothing unusual in this: confronted with sudden disaster we all focus on how unremarkable the circumstances were in which the unthinkable occurred.” (Didion, p.4)

In the span of seconds, we become widowed, orphaned, brother-, sister-, friend-, childless, and no manual will lay out for us how to process what has happened and how to resume our lives. We feel helpless when confronted with grief, and it’s a long-lasting struggle not only because death feels sudden but also because grief is a messy, complex and multifaceted emotion that comes in waves and because society shames people experiencing so-called negative feelings.

Since grief is anything but straightforward, it’s difficult to give a definition, however tentative. In C.S. Lewis’s experience, grief feels like fear (Lewis, p.5) and like suspense, as if he was “waiting for something to happen. It gives life a permanently provisional feeling.” (Lewis, p.29) To him, this feeling “comes from the frustration of so many impulses that had become habitual. Thought after thought, feeling after feeling, action after action, had H. for their object.” (Lewis, p.41) Deprived of a crucial point of reference, he has lost his bearings somehow, and lacks focus and the motivation to do simple tasks: “I loathe the slightest effort. […] Even shaving. What does it matter now whether my cheek is rough or smooth? […] It’s easy to see why the lonely become untidy.” (Lewis, p.7)

While some people in grief put their lives on hold, other people grow restless and overpack their schedules to try and forget about their distress. Some stop eating, others overeat, and yet others alternate between two extremes. There’s no right way to ‘do’ grief. Still two constants seem to emerge, besides the feelings of sadness, loneliness and regret: the repercussions on physical health and the resistance to self-pity.

Joan Didion, who’d lost both of her parents before losing her husband, didn’t grieve for John in the same way she did for her parents. Regarding her grief over her parents’ death, she recalls feeling “sadness, loneliness (the loneliness of the abandoned child of whatever age), regret for time gone by, for things unsaid, for my inability to share or even in any real way to acknowledge, at the end, the pain and helplessness and physical humiliation they each endured.” (Didion, pp.26-27)

By “physical humiliation,” Didion might mean the physical symptoms among the bereaved which include “tightness in the throat, choking with shortness of breath, need for sighing, and an empty feeling in the abdomen, lack of muscular power.” (Didion, p.28) Grieving people can “gr[o]w faint from lowered oxygen, […] [clog] their sinuses with unshed tears and [end] up in otolaryngologists’ offices with obscure ear infections.” (Didion, pp.46-47) I know someone whose grief affected her memory, broke her voice a little, and caused her to develop vitiligo. “I had a strong psychosomatic reaction to it,” she said.

Didion also observes that people in grief have a striking look when they’re caught off guard:

People who have recently lost someone have a certain look, […] one of extreme vulnerability, nakedness, openness. It is the look of someone who walks from the ophthalmologist’s office into the bright daylight with dilated eyes, or of someone who wears glasses and is suddenly made to take them off. These people who have lost someone look naked because they think themselves invisible […], incorporeal. (Didion, pp.74-75)

When she unexpectedly saw people who’d lost a spouse or a child, for example, “during the year or so after the death[,] [w]hat struck [her] in each instance was how exposed they seemed, how raw. How fragile.” (Didion, p.169)

The pain of losing someone you love is so excruciating that it sometimes feels like it could be fatal. Yet C.S. Lewis “almost prefer[s] the moments of agony” which are “clean and honest,” unlike “the bath of self-pity, the wallow, the loathsome sticky-sweet pleasure of indulging it.” (Lewis, p.6) According to Didion, “[p]eople in grief think a great deal about self-pity. […] We fear that our actions will reveal the condition tellingly described as ‘dwelling on it.’ We understand the aversion most of us have to ‘dwelling on it.’” (Didion, p.192)

Our aversion to self-pity seems unjustified though. Not only is self-pity natural given the circumstances (“We are repeatedly left, […], with no further focus than ourselves, a source from which self-pity naturally flows” [Didion, p.195]) but, as Didion puts it, we even have “urgent reasons” to feel sorry for ourselves: “consider those dolphins who refuse to eat after the death of a mate. Consider those geese who search for the lost mate until they themselves become disorientated and die. In fact the grieving have urgent reasons, […], to feel sorry for themselves.” (Didion, p.193) So, really, it is okay to feel sorry for yourself for a time.

What Clears Out a Room

The narrator in Douglas Coupland’s Miss Wyoming says, “If he’d learned one thing while he’d been away, it was that loneliness and the open discussion of loneliness is the most taboo subject in the world. Forget sex or politics or religion. Or even failure. Loneliness is what clears out a room.” The same could be said of grief – though the two are linked.

Both individual history and social norms shape the ways humans experience emotions, including grief. When she was grieving for her mother, Nussbaum was torn as a daughter and professor because of the lack of clarity, of consistency, regarding social norms. As a result, she felt guilty, as if whatever she was doing was the wrong way to grieve according to Western culture:

One is supposed to allow oneself to “cry big” at times, but then American mores of self-help also demand that one get on with one’s work, one’s physical exercise, one’s commitments to others, not making a big fuss. […] I felt guilty when I was grieving, because I wasn’t working on the lecture; and I felt guilty when I was working on the lecture, because I wasn’t grieving. […] I oscillated between the belief that it is a sign of respect and love to the dead to focus on loss and sadness, and the belief that one should distract oneself and go about one’s business, showing that one is not helpless. (Nussbaum, pp.140-142)

In a similar way, Sandra M. Gilbert “had a strange and strangely muffled sense of wrongness – ‘of being an embarrassment.’” (Gilbert, Preface, XX) She felt “that in [her] sorrow [she] represented a serious social problem to everyone except [her] circle of intimates, confronting even well-wishers with a painful and perhaps shameful riddle.” Yet Gilbert’s research showed that “this sense of embarrassment, even disgrace, was fairly common among the bereaved.” (Gilbert, Preface, XIX)

As a child I was embarrassed about my dad’s death. All my peers had dads, so I didn’t dare to say mine was dead. When someone would ask me, “what does your dad do?”, I would just say “he’s an engineer.” DIY activities for Father’s Day were a bit of an ordeal. I remember finding it difficult to have to craft a present, knowing that I’d never give it to the person it was intended for.

Because their sorrow is socially embarrassing, even shameful, the bereaved feel the need to conceal their fragility and to even hide themselves: “For weeks, […] I simply couldn’t bear to appear in public, couldn’t enter (even) a supermarket or a drugstore, so ‘exposed, weak, vulnerable’ did I feel.” (Gilbert, p.261)

Photo by Kristina Tripkovic on Unsplash

In A Grief Observed, C.S. Lewis mentions an “invisible blanket between the world and [him]” (Lewis, p.5) and thinks that some people consider him not a mere embarrassment but something like the personification of death itself: : “I see people, as they approach me, trying to make up their minds whether they’ll ‘say something about it’ or not. […] To some I’m worse than an embarrassment. I am a death’s head.” (Lewis, p.11) Death sounds like a taboo subject, even with his children: “I cannot talk to the children about her. The moment I try, there appears on their faces […] the most fatal of all non-conductors, embarrassment. They look as if I were committing an indecency. […] I felt just the same after my own mother’s death when my father mentioned her.” (Lewis, p.10)

Gilbert argues that, since bereavement is almost as problematic as death, the computer screen may serve as a safe space to both express our own feelings of loss and send words of comfort to others: “it’s no wonder that sufferers feel freest to air their feelings of loss when they’re most alone – at the glimmering computer screen. And it shouldn’t surprise us either if words of consolation are easiest to utter when they’re articulated in silence, on a keyboard.” (Gilbert, p.247)

Unwritten social rules demand of us that we act as if our world wasn’t falling apart but, thanks to mutual understanding, we acknowledge the need to mourn the loss of someone we love and find it appropriate. No wonder so many of us are torn.

Grief Comes in Waves

When someone you love dies, and you’re not expecting it, you don’t lose her all at once; you lose her in pieces over a long time—the way the mail stops coming, and her scent fades from the pillows and even from the clothes in her closet and drawers. Gradually, you accumulate the parts of her that are gone. Just when the day comes—when there’s a particular missing part that overwhelms you with the feeling that she’s gone, forever—there comes another day, and another specifically missing part. John Irving, A Prayer for Owen Meany

When a loved one dies, not only do you lose several people in one, as discussed in a previous point, but you also lose them in pieces, gradually, bit by bit. C.S. Lewis’s words echo this thought: “I was wrong to say the stump was recovering from the pain of the amputation. I was deceived because it has so many ways to hurt me that I discover them only one by one.” (Lewis, p.52)

As time goes by, you slowly start to feel better on some days, but grief is anything but a linear journey: “Grief comes in waves, paroxysms, sudden apprehensions that weaken the knees and blind the eyes and obliterate the dailiness of life.” (Didion, p.27) Grief tends to come in bigger waves at milestones (graduation ceremonies, first jobs, weddings, births, family celebrations), but the emotional agony of the earlier days of grief can also hit you in the feels again, with full force, when you wake up after your deceased loved one has appeared in your dream, for instance – which is both disturbing (it looks so real) and pleasant (you get to see them again) – or on ordinary days. It’s as if s/he had died all over again. “Tonight all the hells of young grief have opened again; the mad words, the bitter resentment, the fluttering in the stomach, the nightmare unreality, the wallowed-in tears. For in grief nothing ‘stays put.’ One keeps on emerging from a phase, but it always recurs. Round and round.” (Lewis, p.49)

This year marks the 19th anniversary of my father’s death. On Christmas Day last year, my sister had compiled a list of my parents’ favorite songs. They were playing in the background while we were eating. I said as a joke, “Of course you had to choose the saddest songs. Mom’s going to cry.” In fact, I was trying to divert attention from my own pang of nostalgia and sadness. When Robin Gibb sang the line “till I finally died, which started the whole world living,” I choked back tears. The Bee Gees’ ‘I Started a Joke’ was my father’s favorite song. I listened to it alone a few days after Christmas Day, in floods of tears.

All in all, grief is made of ups and downs, with silver linings even in the darkest hour:

One never meets just Cancer, or War, or Unhappiness (or Happiness). One only meets each hour or moment that comes. All manner of ups and downs. Many bad spots in our best times, many good ones in our worst. One never gets the total impact of what we call ‘the thing itself.’ […] It is incredible how much happiness, even how much gaiety, we sometimes had together after all hope was gone. How long, how tranquilly, how nourishingly, we talked together that last night! (Lewis, p.13)

Grief survivors will tell you: grief is not made of one neat phase after the other and, after a year, we’re not done grieving. “Grief is wearing a dead person’s dress forever,” the last line of Victoria Chang’s poem ‘The Blue Dress’ reads. We might go through the ‘acceptance phase’ many times, for instance: “In grief, given our propensity to distance ourselves and deny what has occurred, we may have to go through the act of accepting many times.” (Nussbaum, p.46)

Nora McInerny discusses happy, sad, and bittersweet memories in her TED talk and calls grief a “multitasking emotion.” The various emotions we experience when we’re grieving don’t cancel each other out. She also shows that people who’ve lost their partner can fall in love again while still grieving over their late spouse:

Grief doesn’t happen in this vacuum, it happens alongside of and mixed in with all of these other emotions. […] falling in love with Matthew really helped me realize the enormity of what I lost when Aaron died. And just as importantly, it helped me realize that my love for Aaron and my grief for Aaron, and my love for Matthew, are not opposing forces. They are just strands to the same thread. […] grief is this multitasking emotion. […] you […] will be sad, and happy; you’ll be grieving, and able to love in the same year or week, the same breath.

No Such Thing as Moving On

A long-distance friend’s kind words helped me tremendously to stop feeling bad about my inability to move on in the twinkling of an eye and in a straight line. By the end of our lives, we’ll have grieved an awful lot of beings, things, places, and periods of time. As you know, there are many forms of grief. At that time, I was missing someone terribly. This person was still alive but had, to all appearances, moved on, while I hadn’t. I felt like I was doing all the loving and all the missing, in a way, and it was hard to accept that I was faring much worse than him. My friend wrote, “Even dwelling sadly on an almost-love lost is a form of moving on, because today in your thoughts you are not where you were yesterday, or six months ago […] You are forever ‘moving on.’ And life is not linear, one can always move on in circles, spirals, meandering pattern, go backwards, forwards, sideways, rise and fall… and there is even movement of a sort in rest.” I hope his words will warm your heart a little, as they did mine.

“What if we got rid of the phrase ‘move on’ and instead began to move with and move through our losses?” Kelley Lynn suggests in her TEDx speech.7 The core message of Nora McInerny’s TED talk is similar: we don’t move on from grief, we move forward with it: “[The painful experiences] […] mark us and make us just as much as the joyful ones. And just as permanently. […] we don’t look at the people around us experiencing life’s joys and wonders and tell them to ‘move on,’ […] what you’re experiencing is not a moment in time, it’s not a bone that will reset, […] you’ve been touched by something chronic. Something incurable.”

Also, the strange thing is, we come to grieve over moments we didn’t or won’t share with the people we’ve lost, moments that belong to a past they were absent from and to a future they won’t get to experience. Addressing his late wife, C.S. Lewis writes, “You have stripped me even of my past, even of the things we never shared.” (Lewis, p.52)

My father’s legacy is made up of joy and sorrow. After his death, mail from the Jehovah witnesses kept coming for a little while. He wasn’t a member. He just had a pleasant conversation with a man who had rung at the door one day and, although he didn’t agree with his views, let him put flyers in the mailbox. Letters from Handicap International also kept coming for years. Inheritances from his difficulty saying ‘no,’ his generous heart. My father gave his guitar to a dear friend once. He could also empty his pockets for someone in the streets. He’d let us have all the pets we wanted – rabbits, dog, hamster, guinea pigs, birds, chinchilla, salamander, mice, turtles, fish.

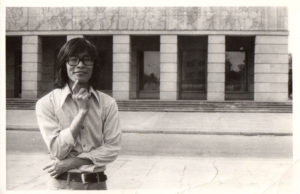

Dad’s bedside picture

My father also gave me a taste of what it’s like to be loved, which might have shaped both my idea of love and my expectations. He’d keep his favorite photo of me on his bedside table. He died of a cerebral hemorrhage 9 days before my 10th birthday. I had made a kind of list of arguments to persuade him to give me a lop-eared rabbit as present. He had put it in his suitcase, making a silent promise. I didn’t know these two things until someone told me and we sorted through his stuff at his boyhood home in Vientiane where he’d stay when he’d be away for work. I can’t help wondering at times, will another man ever keep a photo of me on his bedside so that I’m the last face he sees before he turns the light off and falls asleep? will someone ever pack a silly wish list I’ve made?

“Sans issue,” my drawing

Still it can be dangerous to idealize the dead and think life would have been different in the best possible way, if they were still alive. My father had many faults, which I became aware of well after his death. The ‘what if’ questions often take a certain form, as discussed further above, but they can be phrased differently – not to show that it can always be worse, but just to realize how little we know of what might have been: what if we had grown apart over the years? what if he had woken up from the coma and had to live with devastating after-effects?

The things I was left with were, for the most part, gaps I had to fill – not only unanswered questions I learned to live with, but also entire periods of time I had to figure out without his help. I remember watching a lot of movies about father-daughter relationships or films with mentors. From the age of 10, I grew up without a real father figure, so I was trying to live vicariously through those heroines, to get a glimpse of what it’s like to grow up with a father as a teen or young adult. As a grief survivor you may have had to fill some gaps, too, and to move forward as best you could. You may, in fact, still be learning how to move with your loss.

Tomorrow, the Bowl I Have Yet to Fill8

“It doesn’t seem worth starting anything. […] Up till this I always had too little time. Now there is nothing but time. Almost pure time, empty successiveness.” (Lewis, pp.29-30) After a loved one’s passing, even if the loss has made you become more fully conscious of the ephemerality of life, it might seem like you have more time than ever before and you don’t know what to do with it. Your life has been pending, and to begin again seems like a mountain to climb.

We know the throes of grief must make way for what is to come next but precisely, what will follow? In his account of his experience of grief, C.S. Lewis writes that the times when he’s not thinking about his wife may be his worst because then something amiss spreads over everything, and he realizes how uncertain and scary the future is. “I see the rowan berries reddening and don’t know for a moment why they, of all things, should be depressing. […] What’s wrong with the world to make it so flat, shabby, worn-out looking? Then I remember. This is one of the things I’m afraid of. The agonies, the mad midnight moments, must, in the course of nature, die away. But what will follow?” (Lewis, p.31)

As harrowing and strange as the year following your loved one’s death may have been, you may be reluctant to say goodbye to that year because it means the images of your love will become more distant. As Joan Didion writes,

I did not want to finish the year because I know that as the days pass, […] My image of John at the instant of his death will become less immediate, less raw. […] My sense of John himself, John alive, will become more remote, even “mudgy,” […] All year I have been keeping time by last year’s calendar: what were we doing on this day last year, […] I realized today for the first time that my memory of this day a year ago is a memory that does not involve John. […] I know why we try to keep the dead alive: we try to keep them alive in order to keep them with us. (Didion, p.225)

Yet what if you let the days do themselves (not by indulging in idleness, but by leaving room for surprise and, most of all, for self-compassion)? How about letting the days reveal themselves to you, one by one? “About five in the afternoon on the 24th I thought I could not do the evening but when the time came the evening did itself.” (Didion, p.223)

We may not feel ready to let go of our solid anchor to the past just yet, but “if we are to live ourselves there comes a point at which we must relinquish the dead, let them go, keep them dead. Let them become the photograph on the table.” (Didion, pp.225-226)

My father during his ‘hippie’ years, before he became a father

It might also be a good idea to shift our attention to the people who are still here, and to be aware of our finitude and mortality without letting this awareness unsettle and cripple us. You will leave behind people who you love and who love you, so you might want to ask yourself, as Tanya Villanueva Tepper suggests in her TEDx talk,9 “what are you doing now to inspire and strengthen those who you love to keep living without you when you’re gone? How do you want to be remembered? And how will you want your loved ones to be treated when they’re grieving over you?” These questions may inspire us to live with more compassion (we want our loved ones to be treated well in the course of and after our lives) and intention (we all want to be remembered in a certain way – no one wants to be deemed disposable).

Another thing we can do for ourselves is to keep learning, and to trust that life still has a lot to teach us and surprise us with. When you have trouble finding reasons to stay alive, please turn to your curious nature. I believe we’re all curious to varying degrees, and learning can be an antidote to sadness:

The best thing for being sad, […], is to learn something. […] You may grow old and trembling in your anatomies, you may lie awake at night listening to the disorder of your veins, you may miss your only love, you may see the world about you devastated by evil lunatics, or know your honour trampled in the sewers of baser minds. There is only one thing for it then — to learn. Learn why the world wags and what wags it. T.H. White, The Book of Merlyn

Teaching others about some of the things you’ve understood along your grief journey, for example, could prove helpful, too.

I also find that reading poetry can help a great deal. I’d recommend The Art of Losing: Poems of Grief & Healing edited by Kevin Young and, secondarily, Poems of Mourning edited by Peter Washington. Here are some of the poems that particularly move me: ‘Long Distance II’ by Tony Harrison, ‘Those Winter Sundays’ by Robert Hayden, ‘Otherwise’ by Jane Kenyon, ‘Nothing Gold Can Stay’ by Robert Frost, ‘The Shout’ by Simon Armitage, ‘Father’ by Ted Kooser, ‘Funeral Blues’ by W. H. Auden, ‘One Art’ by Elizabeth Bishop, ‘Speaking to my Dead Mother’ by Ruth Stone, ‘What Survives’ by Rainer Maria Rilke (trans. A. Poulin) and ‘Music when Soft Voices Die’ by Percy Bysshe Shelley

Finally, what if the antidote to death, to loss and grief, was to give birth to projects and dreams and to do everything we can for them to materialize?

How Wonder Can Help Survive Grief

In grief, with the realization that we start feeling better comes a kind of shame and a feeling that we must prolong our unhappiness. (Lewis, p.46) The first laughs after the loss will likely meet with a sense of betrayal. You’ll also feel guilty, when you realize one morning that the person you’ve lost wasn’t your first thought upon waking.

Yet the time will come when we have to lift the sorrow, if only to see with greater clarity: “after ten days of low-hung grey skies and motionless warm dampness, the sun was shining and there was a light breeze. And suddenly at the very moment when, so far, I mourned H. least, I remembered her best. […] It was as if the lifting of the sorrow removed a barrier. […] You can’t see anything properly while your eyes are blurred with tears.” (Lewis, p.39)

“Passion grief,” as C.S. Lewis calls it in A Grief Observed, increases the distance between you and your loved one instead of bringing you two closer. Gladness and laughter appear to be the gateway to a stronger connection with the deceased, and bring out truer memories:

passion grief does not link us with the dead but cuts us off from them. […] It is just at those moments when I feel least sorrow – […] – that H. rushes upon my mind in her full reality, her otherness. Not, as in my worst moments, all foreshortened and patheticized and solemnized by my miseries, but as she is in her own right. […] I will turn to her as often as possible in gladness. I will even salute her with a laugh. The less I mourn her the nearer I seem to her. (Lewis, pp.47-48)

Because of the nature and complexity of our emotions, grief and joy – and anger and gratitude, for example – have a dynamic relationship to each other. (Nussbaum, p.87) Martha Nussbaum asserts that it’s possible to find a sort of wonder in grief “in which one sees the beauty of the lost person as a kind of radiance standing at a very great distance from us.” She quotes Proust’s narrator describing his mourning for Albertine in Remembrance of Things Past (Nussbaum, p.54):

My imagination sought for her in the sky, at nightfall when we had been wont to gaze at it while still together; beyond that moonlight which she loved, I tried to raise up to her my tenderness so that it might be a consolation to her for being no longer alive, and this love for a being who was now so remote was like a religion; my thoughts rose to her like prayers.

“Prayers,” illustration by Judy Clement Wall

S/he who looks for wonder in grief isn’t naive. There’s nothing corny about wonder. Rather, it’s essential for many emotions and can help us cope with hardships. Recourse to wonder isn’t a miracle cure but it can help along the grief journey. Let’s try to keep paying tribute to our beloved ones by going to the places they used to go to, remembering all the things they loved – doing little things in homage to them. Perhaps we can only find comfort in knowing that our loved ones are all around us, every time, and that they will never be truly gone as long as we cherish them in memory, until we stop feeling and thinking, until we ourselves draw our last breath. For they are always with us in our hearts and minds, and always will be.

Nora McInerny has noticed that the bereaved easily slip into the present tense, not because they’re in denial or forgetful but because the people they love who they’ve lost are still present for them. She says, “[Aaron]’s present for me in the work that I do, in the child that we had together, in these three other children I’m raising, who never met him, who share none of his DNA, but who are only in my life because I had Aaron and because I lost Aaron. He’s present in my marriage to Matthew, because Aaron’s life and love and death made me the person that Matthew wanted to marry.”

A famous line in John Steinbeck’s The Winter of our Discontent reads, “It’s so much darker when a light goes out then it would have been if it had never shone.” You may be in the dark right now: the beautiful light that had brightened up your existence went out. Isn’t it wonderful though to have had the chance to watch this light while it shined in all its splendor? Isn’t it wonderful that we’re capable of loving someone so much that, when s/he dies, the love doesn’t and instead lives on?

Still, how about someone accompanying a loved one through terminal illness? How do you look for wonder in grieving for someone who’s still alive but no longer the same person s/he used to be? What is left to treasure in a situation where, before s/he passes away, your parent has become dependent on your assistance? An awful lot, it turns out, if we see past the obvious, the fears and all the unglamorous things caring for a dying loved one entails. Philip Roth, who nursed and supported his father through his battle with a brain tumor, writes in Patrimony, “once you sidestep disgust and ignore nausea and plunge past those phobias that are fortified like taboos, there’s an awful lot of life to cherish.” (Roth, p.123)

Then when someone we love dies, we can hardly bear the sight of their dead body, but still we can’t overlook their value. As Nussbaum explains, “the same sight that is a reminder of value is also an evidence of irrevocable loss.” (Nussbaum, p.30) When somebody of enormous value to us passes away, the loss is especially significant. As is life, so is grief: a ragbag of contradictory emotions that reinforce rather than negate one another, a confusing ragbag indeed where beauty and pain coexist.

How to Help Someone in Grief

Even though I’d been there myself, I’d feel clumsy and inarticulate when someone I knew had just lost a loved one. Everyone’s different when they’re hurting: some need their space, while others rely on active communication with other people. So, I was terrified of getting it wrong, and of coming across as intrusive. What do you say to somebody whose world has just fallen apart? What helped me at that time might not help them. I’d put enormous pressure on myself to find the words that’d make all the difference. Today I realize my intentions were good, but my approach misguided: in fact, there’s no need to say much. The most important thing is to listen intently, to invite the person who’s grieving to tell you more about both their feelings as they’re dealing with loss and the kind of person their loved one was, and to do tangible things for them.

Quite a lot of us find that doing something specific for a grieving friend can help a great deal. Why not invite them to go for a walk, make hot chocolate, bring a homecooked meal, pick the kids from school, bring flowers, do a chore for them (e.g. sorting the mail, cleaning the floor, doing the laundry)? Yvonne Heath suggests in her Tedx talk that we “just show up.”10 In a similar way, Kate Schutt encourages us to “stop thinking about it” and “just act.” She explains that it’s better to risk coming across as intrusive than to be silent or absent from your friend or family member’s life. “Risk getting it wrong,” she says.11

It seems to make sense to ask the grieving person how you can best support them or what would make them feel better or if there’s anything you can do, but in fact they themselves often can’t figure out what they need in this challenging time. We’re also tempted to say, “call or text me if you need me” not to sound pushy, but the grieving person would rather not come across as a burden either.

When my sister’s beloved dog Robbie died of a brain tumor, I gave her a bracelet with the letter ‘R’ which she wears all the time. When her boyfriend and she came over shortly after they lost Robbie, I remember baking an apple pie – it was a wink of sorts as it was Robbie’s favorite. Just having them sleep over, letting them talk, and focusing on making them feel warm and cared for seemed to be enough, if only for a few hours.

Truly, a small gesture can go a long way, even when someone is at rock bottom. They might not show their appreciation at that instant but chances are they’ll still remember it years later with deep gratitude. One evening I was drying my hair. I had reached what remains to this day my lowest point. I was sobbing in front of the mirror, drying my hair. My eldest sister saw me at that most vulnerable moment. She just took the hairdryer from my hand and finished drying my hair, without a word. I was so moved by this simple gesture that I remember it to this day. When the words fail you, please remember that it’s okay to feel powerless and inarticulate, and that you can still hold the grieving person’s hand, hug them, or show you care in a different way.

This video by Megan Devine and Refuge in Grief addresses how you can help a grieving friend. Megan Devine suggests joining your friend in their pain by acknowledging that things are as bad as they feel to them rather than giving them advice or cheering them up. For instance, you could say, “I’m sorry that’s happening. Do you want to tell me about it?” As Devine says, “you can’t heal somebody’s pain by trying to take it away from them.” Your friend doesn’t need fixing, s/he just wants to be heard out.12

In her speech ‘Rethinking How We Hold Space for Grief and Loss,’ Michèle Pearson Clarke suggests that we say “I’m sorry you’re hurting. Can you tell me what it’s like for you right now?” for example.13 By inviting our grieving friend, family member or colleague to tell us more, we’re letting them know that we’re here to lend them an attentive ear.

The main idea might be to let the grieving share their stories. As Kelley Lynn suggests in her TEDx talk, “Love grows more love. All good things are born out of love. So what if instead of saying to someone, ‘hey, stop talking about your brother,’ we say ‘tell me more about your brother who died’? What if instead of trying to fix people we sat with them inside of their pain and we let them tell us what comes next?”

Stories

I asked 8 people three questions not to try and pinpoint grief, but rather to hear their stories because they matter.

I was afraid they would reject my invitation to contribute. After all, I was asking them to pull open a drawer they might have kept locked for years, to go back to a chapter of their life they would perhaps rather not reread. While letting them choose between anonymity, visibility or something in between, I was asking them, in short, to reveal intimate parts of themselves.

I was hoping that the stories would help you and me as readers, and that the exercise would have cathartic effects for the respondents as well. It felt strange: in a sense, I was asking them a favor with the intention of being of service. I believe storytelling can be very therapeutic indeed. This reminds me of one of my favorite passages in Zora Neale Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God: “They sat there in the fresh young darkness close together. Pheoby eager to feel and do through Janie, […] Janie full of that oldest human longing – self-revelation.”

Much to my joy, they didn’t reject my invitation. I found solace in the different answers, and hope that they’ll resonate with you, too, and that you’ll recognize yourself in them. I think they show that, although grief is a universal emotion, the ways we experience it as individuals are very personal and, therefore, subjective.

Thank you to the contributors <3

1) Grief is… (what word do you most strongly associate with grief? Choose the first word that comes to mind. It can be a word full of imagery. It can be something abstract or concrete)

“absence.” – Jadwiga

“numbing.” – Oliver

“bereft: deprived of or lacking (something). Bereft is a hole where something should be, once was and now isn’t. Nothing else will fill that particular hole, except perhaps God.” – Tobias Mayer

“messy (and unpredictable).” – Judy Clement Wall

“love.” – Sarah Davis, creator of ‘Breathing Wind,’ “a podcast about what it feels like to lose parents.” (I’m grateful for our collaboration on Episode 25 of Season One)

“loss.” – Gordon

“loss. I know that’s a word which often comes associated with grief, ‘I’m sorry for your loss’, but I feel like ‘grief’ is the longer haul journey that comes with a loss. For me, I think the immediate feeling that comes when someone dies, is loss. Like losing a limb. Something is gone. Lost.” – Jayde Perkin

“inevitable.” – Sally Pendreigh

2) What particularly striking moment do you remember when you were grieving for someone you love? Even a very mundane moment or detail can turn out to me revelatory. Something that made you consider yourself or life in a new light, an eye-opener of sorts, a lesson, a wink

“A town hall employee’s benevolence shortly after my husband died. She got misty-eyed, while it’s paperwork she does every day. She didn’t just do her job. She wrote down helpful information, and told me exactly where to go. She was very human about it… To this day I’m still moved to tears by this complete stranger’s kindness.” – Jadwiga

“What has been striking was not a particular moment but the fact that I haven’t produced a single tear. I feel that this is striking since I otherwise have no problem doing so. I have been thinking about why I might have had this reaction (or rather the absence of this reaction) and I wonder whether it was because I didn’t want to accept the situation. What I mean is: if I didn’t produce any tears the loss would turn out to be a bad dream.” – Oliver

“For Frank,14 I remember crying floods, like I hadn’t cried before (except in drunken self-pity) I cried for him, for me, for us, for the world that had lost his presence. The wonderful thing about this crying was I realised I could cry, for real, for others and not myself. I was reminded of my humanity which I for so long doubted.” – Tobias Mayer

“I was on vacation, sitting in the sweet little glass ceiling atrium of our Airbnb, reading a book. There was this funny, beautifully written paragraph that I read two times just for the pleasure of reading it, and I thought suddenly and unexpectedly of my father. We weren’t close when he was alive. We had a complicated relationship, made all the more so in the last few years of his life by the fact that he suffered from dementia and simply was not the same man I’d grown up with. He got really sweet at the end of his life, and befuddled. Such an odd thing to realize that this brilliant, impatient, emotional bully I’d spent most of my life being mad at didn’t exist anymore… even though a man who looked just like him was right there in front of me. Anyway, the one thing we shared was a love of books. We often shared books with each other. I thought of him in that moment while I was reading, and suddenly realized I was crying. He’d died about four months before, but this was the first time I truly felt his absence, like a hole in the world where he used to be. It was weird, and I remember feeling both incredibly sad, and a tiny bit relieved because the sadness felt appropriate, like I was, for the first time, ‘doing grief right.’” – Judy Clement Wall

“My dad had a love affair with the Camino de Santiago. For 20 years, he researched it, collected books, designed the perfect Camino trekking stick, and started imagining himself on the Camino for his 70th birthday. Having a few health setbacks, my mom discouraged him from going unless he trained for it, and he never made it. A few months after he passed, I decided to make the pilgrimage with him. I brought his ashes to Spain and began my journey. I met up with a friend, who kept urging me to part with the ashes, but I was hesitant. Finally, I decided to do this, and he helped. He created a ceremony around the ashes. We stood in the water, and he said something beautiful that I don’t remember. As soon as my dad’s ashes touched the water, a large fish jumped out of the water. From that day forward, I continued to spread his ashes on the trail, led by my intuition and by myself. I sought out the perfect spot and had a conversation with my dad. I felt so much more connected to him from that day forward. A few years later, I visited Spain again and felt his presence. He is always with me, but he’s especially when I am hiking in Spain.” – Sarah Davis, creator of ‘Breathing Wind,’ “a podcast about what it feels like to lose parents”

“When I was 17 I saw my Grandma laid out to rest, I remember thinking whatever she was, was greater than the bones and flesh laid out before me. I knew then that there was a clear separation between body and spirit.” – Gordon

“A few weeks after my mum died, my dad and I had been sorting out some of her things, and had taken a binbag of her clothes down to the local charity shop. I’d sort of forgotten about it, and a few weeks after that, I was walking down to the pub to see some friends, and walked past the charity shop, and the mannequin in the window was dressed in my mum’s clothes. That was a strange feeling. Sometimes with grief, you are swimming through it for days, weeks, months. And then sometimes you can just feel really empty, just dipping your toes, and then all of a sudden it hits you like a big wave.” – Jayde Perkin

“My amazing and much-loved mum died in January 2010. About a year later, I found myself reading an article in a magazine about Rufus Wainwright (American – Canadian singer). His mum had died in the same month as mine. And he said he’d come across a saying (unattributed) that ‘Your mother gives birth to you twice. Once when you’re born and the second when she dies’. Wow! That really resonated with me then and still does today. That’s exactly how it felt for me. This person – who gave birth to me, had always been there and was my best friend – was gone. Everything had changed and I was in a whole new situation, without her. Her death gave me cause to look at my life. What did I want out of it? I saw what she’d sacrificed and I wanted to learn from that. At work, something I’d been working on for two years was pulled the day before the results were to be published. It was the final straw. I left the organisation I’d been employed by for 26 years, and that also meant me leaving my husband (we’re now back together). I went off to train as a counsellor and it’s a job I’ve been doing ever since and which I love to my bones. My mum would have loved what I do now, though she would have worried hugely about me leaving such a secure job and would have hated that my husband and I separated at all. In the words of a poem (called ‘Legacy’) that I wrote about my mum two years after her death, ‘You’ve left me with the strength to face new challenges, the courage to seek new directions and a will to do justice to the life you gave me’.” – Sally Pendreigh

3) What’s the most helpful thing someone has said or done for you after you lost a loved one to alleviate the pain? Again it can be something tangible (an unannounced visit to bring you a homemade meal, for example) or simple words that made a huge impact or a gesture of affection that you needed and that moved you

“Witnessing my children’s courage while they were in pain, too. They’d encourage me and tell me their dad loved me, when I’d have moments of doubt. I wasn’t alone. If my children hadn’t been there, I would have fallen to pieces.” – Jadwiga

“The most helpful thing someone has said or done for me was actually the deceased person herself. She had written a few lines about what I meant to her.” – Oliver

“The best thing a person can say is nothing, just to be there, to be close to listen, to hear. I didn’t need anything from anyone at that time, or when my parents died, except to be acknowledged, to be heard. Anything else, any words beyond simple condolence felt invasive.” – Tobias Mayer

“I don’t remember who said it, but someone said that grief comes in waves, often when you least expect it. I found that reassuring somehow, and true. I liked the idea that other people had experienced something very much like what I was experiencing. The ways in which we’re all the same, and all connected, are always comforting to me.” – Judy Clement Wall

“What stands out to me is how my friends supported me in tangible ways immediately after my loss. It was hard for me to accept their help, but when I leaned in, I felt so supported and filled with gratitude.

-It was the day before New Year’s Eve when my dad passed away. I had flown out to Seattle to celebrate with a friend, and we were just finishing a large meal when my mom called me. I looked at the time – it was 9pm Seattle time, which meant it was 11pm her time – and very unusual for her to be awake. I answered and she just said, “Dad’s dead.” It was hard for me to hear; I had just seen him alive the week before and thought he’d be OK. He was clearly suffering from cancer and very tired, but it didn’t seem like an emergency. Perhaps that was my denial. I told that friend what happened, and she offered to fly me back. I couldn’t make a decision, so I left to go to the hotel where I was staying. That evening, I drew myself a bath and cried all the ugly tears. I couldn’t think through the logistics of getting back to Iowa, it all seemed so impossible. So, I called my friend while I was still in the bathtub and asked her to help me get back. She worked her magic (and her miles) and made it happen, also getting a refund for my hotel stay in the process.

-Another friend picked me up from the airport after I came home. She brought me a bag of Whole Foods salads and soups, something she might not have purchased for herself. She explained that I was healthier than her and she just thought of me when she purchased the items. I remember thinking, this is so odd. I know how to take care of myself. I reluctantly accepted her generosity. And those soups and salads sustained me for a week, when it was hard to leave the apartment for anything.” – Sarah Davis, creator of ‘Breathing Wind,’ “a podcast about what it feels like to lose parents”

“After my grandmother died my grandfather who was crying kissed me on the forehead and said ‘you’ll be alright.’ I thought he was trying to reassure himself but it struck me that he was talking about the long term and things would be alright in the long term, grief is temporary. That helped a lot.” – Gordon

“Words can be really difficult at this time. One of my friends saw me, and he just put his arms around me, and he didn’t say anything, he just gave me the biggest hug, for ages. and that’s exactly what I needed.” – Jayde Perkin

“I wrote a poem (a different one from the one mentioned above) for my mum’s funeral. It was very personal and I didn’t think I’d be able to read it on the day. I asked her favourite nephew if he would read it for me. He had a look at it and said, ‘No, I can’t do that. This is personal, you need to read it yourself’. He’s an actor and he told me ‘You’ll be able to do it if you practise, practise, practise’. I wasn’t convinced but I did as he said. I practised so much I can still recite the poem word-for-word now, ten years later. And I was able to get through it on the day. It reminded those who knew her of some of the stories they’d heard her tell. And it gave others who didn’t know her (so well) a flavour of who she was and the things that she did. People told me it was one of the best funerals they’d ever been to. And it turned out that being able to do what I did on the day was a major part of my healing from the loss. It also led to me training and becoming a funeral celebrant, because I wanted to help other families give their loved ones the sort of send-off they deserved. All that from my cousin saying ‘no’ to me, something I really didn’t want to hear at the time.” – Sally Pendreigh

So, tell me. What is it like for you right now? If you’ve lost someone you love, do you want to tell us about the kind of person s/he was? Please don’t hesitate to answer any of the three questions above as well, if you feel like it. Thank you for reading <3

1. Joan Didion, The Year of Magical Thinking (London: Fourth Estate – HarperCollins Publishers, 2012), p.35. All references are to this edition. Further cited in the text and shortened to author’s name and page number.↩

2. Nora McInerny, “We Don’t ‘Move On’ from Grief. We Move Forward with It.” TED. https://www.ted.com/talks/nora_mcinerny_we_don_t_move_on_from_grief_we_move_forward_with_it (accessed April 14th, 2020).↩

3. Sandra M. Gilbert, Death’s Door: Modern Dying and the Ways We Grieve (New York: W.W. Norton & Company), p.64. All references are to this edition. Further cited in the text and shortened to author’s name and page number.↩

4. Martha C. Nussbaum, Upheavals of Thought. The Intelligence of Emotions (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003), p.21. All references are to this edition. Further cited in the text and shortened to author’s name and page number.↩

5. C.S. Lewis, A Grief Observed (London: Faber and Faber, 2013), p.22. All references are to this edition. Further cited in the text and shortened to author’s name and page number.↩

6. Philip Roth, Patrimony: A True Story (London: Vintage – Penguin Random House, 1992), p.125. All references are to this edition. Further cited in the text and shortened to author’s name and page number.↩

7. Kelley Lynn, “When Someone You Love Dies, There’s No Such Thing as Moving On.” TEDx Talks YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kYWlCGbbDGI (accessed April 14th, 2020).↩

8. Title borrowed from Natasha Trethewey’s poem “After Your Death.”↩

9. Tanya Villanueva Tepper, “Grief: What Everyone Should Know.” TED. https://www.ted.com/talks/tanya_villanueva_tepper_grief_what_everyone_should_know (accessed April 14th, 2020).↩

10. Yvonne Heath, “Transforming our Grief by Just Showing Up.” TED. https://www.ted.com/talks/yvonne_heath_transforming_our_grief_by_just_showing_up (accessed April 14th, 2020)↩

11. Kate Schutt, “A Grief Casserole: How to Help your Friends & Family through Loss.” TED. https://www.ted.com/talks/kate_schutt_a_grief_casserole_how_to_help_your_friends_family_through_loss (accessed April 14th, 2020).↩

12. Megan Devine, “How Do You Help a Grieving Friend?” Refuge in Grief. https://www.refugeingrief.com/2018/07/19/help-a-friend-video/ (accessed April 14th, 2020).↩

13. Michèle Pearson Clarke, “Rethinking How We Hold Space for Grief and Loss.” TED. https://www.ted.com/talks/michele_pearson_clarke_rethinking_how_we_hold_space_for_grief_and_loss (accessed April 14th, 2020).↩

14. The name has been changed for the sake of confidentiality.↩

Mes réponses aux trois questions:

1/ acceptation et voyage: c’est un voyage vers l’acceptation

2/ le jour où on a accompagné Robbie dans son derniers voyage, il a neigé. La première neige de l’année. Je me souviens avoir pensé: il a fallu qu’il parte pour qu’il neige alors qu’il adorait ça. Avec le recul, j’aime a penser que les êtres chers communiquent avec nous de cette façon …

3/ toutes les petites attentions aussi variées soient-elles : des gestes, des mots, des silences…