Preamble

Though I’m writing these words in the wake of the recent uprising against the nth instance of police brutality in the U.S. in a long and revolting history, and have been buoyed by the hopeful determination of the BLM1 movement, what I seek to do through this post is add my voice to a broader dialogue on racism. This means including Asians in the conversation. Anti-Black racism and anti-Asian racism aren’t mutually exclusive social constructs. In fact, I think we can’t effectually deal with and put an end to systemic racism without examining how it has crept into many areas of our lives, how social justice issues intersect, how everything is linked. This blog article will discuss the many tentacles of racism, and will then suggest solutions we can implement right now. It will explain how it’s within our power to spread minor miracles and build a more just world.

The Tentacles of Racism

Slavery Residue

In his poignant TED talk “The Symbols of Systemic Racism – and How to Take Away their Power,” Paul Rucker addresses the long-term impact of slavery. Trauma isn’t the only residual of America’s history of discrimination against Black people. Institutional racism pervades all aspects of life in America in a very concrete way, through systems and structures of oppression: police brutality, voter suppression, environmental racism, “disproportionate representation of minorities incarcerated,” and “intentionally segregated neighborhoods, workplaces and schools.”2

Prof. David R. Williams also discusses racial geographies in his speech at TEDMED 2016, “How Racism Makes Us Sick.” He explains how residential segregation by racial group creates racial inequality in the U.S.: your neighborhood context “determines your access to opportunities in education, in employment, in housing and even in access to medical care.”

Racism & Public Health

Speaking of medical care, Williams underlines the fact that “Blacks and other minorities receive poorer quality care than whites.” Research also found that white high school graduates live longer than Black college graduates or Blacks with more education, and that “higher levels of discrimination are associated with an elevated risk of a broad range of diseases from blood pressure to abdominal obesity to breast cancer to heart disease and even premature mortality.”3 Racism thus threatens not only the mental health (it is important indeed to consider the link between racism and mental health) but also the physical health of those experiencing it.

This is particularly relevant today. As Ibram X. Kendi pointed out during an interview on TED earlier this year, “we’re facing […] a racial pandemic within that viral pandemic of people of color disproportionately being infected and dying.”

How the Media’s Narrow Portrayal of People of Color Distorts our Perception of Reality

Mass media and mainstream media constitute an integral part of a system that maintains white supremacy on a pedestal. Here’s how.

Fiction

In fiction, when people of color are present at all, their portrayal is too often but a caricature: they appear on our screens or on paper for form, just so we can check the diversity box. As peripheral characters they tend to help the white protagonist’s story progress, or serve as comic relief sidekicks, or they are so stereotyped they become cartoonish.

White Saviors & the Trivialization of the Black Experience

In her essay “The Solace of Preparing Fried Foods and Other Quaint Remembrances from 1960s Mississippi: Thoughts on The Help,” Roxane Gay takes a critical look at The Help. With its “overly sympathetic depictions of the white women who employed the help; the excessive, inaccurate use of dialect; […] the glaring omissions with regards to the stirring civil rights movement;4” the conspicuous lack of Black male characters; and its implication that white men were unaccountable for race relations and “the sexual misconduct, assault, and harassment” they inflicted upon Black women (BF, p. 215), the movie offers a “deeply sanitized view of the segregated South in the early 1960s.” (BF, p. 214)

That The Help reduces its Black female characters to Magical Negroes – wise, selfless Black characters helping white protagonists move forward – is problematic as well: “Aibileen’s magical power is making young white children feel good about theyselves. […] she uses her magic for her white charge and rarely for herself;” “Minny uses her mystical negritude to help Celia cope with several miscarriages and learn how to cook” (BF, pp. 211-212); and Constantine “is so devastated after being fired by the white family for whom she worked […] she dies of a broken heart.” (BF, p. 215)

It is relevant that the film The Help, based on a novel by a white woman, was written and directed by a white man. As Gay explains, when writing difference, authors run the risk of appropriating a culture that isn’t theirs and of “reinscribing stereotypes, revising or minimizing history, or demeaning and trivializing difference or otherness.” It is, therefore, vital that writers ask themselves how to get race right, and “find authentic ways of imagining and reimagining the lives of people with different cultural backgrounds and experiences.” (BF, p. 216)

Still according to Roxane Gay, the vision of white writers and directors mediate the Black experience in large part. (BF, p. 218) During the screening of Tarantino’s Django Unchained, Gay observed that the ubiquitous use of the N-word was making the white audience laugh while, “[w]hen the movie’s dark humor focused on people who looked like them, the audience was silent.” (BF, pp. 219-220) As Gay writes, the director is “selective about how and where he chooses to honor historical accuracy […] Slavery is a convenient, easily exploited backdrop”: Django Unchained is Tarantino’s way of using “a traumatic cultural experience of a marginalized people […] to exercise his hubris for making […] movies that set to right historical wrongs from a very limited, privileged position.” (BF, pp. 221-222)

Regarding the Black characters in Django Unchained, Django is, for the most part, one-dimensional, and Broomhilda incidental, with little screen time and only a few lines to utter. (BF, pp. 223-224) At the end of The Help, the narrative implies “Celia indirectly empowers Minny to leave her abusive husband.” (BF, p. 212) In a similar way, in Django Unchained, it is with the help of a white savior that Django reclaims his freedom, gets back his dignity, and reunites with his wife. Django Unchained, then, is “about a white man working through his own racial demons and white guilt.” (BF, p. 225)

Besides the Magical Negro and the slave, the parts Black actors get to play include “the sassy black friend or the nanny or the secretary or the district attorney […] – roles relegated to the background and completely lacking in authenticity, depth, or complexity.” (BF, p. 59) Roles of maids dominated Hattie McDaniel’s acting career since “domestic servitude was the only way popular culture could conceive of black women.” (BF, p. 227) If you look at contemporary fiction involving Black characters, a lot has changed and, at the same time, a lot has remained the same, if you consider the fact that servitude seems to have taken but another form.

Contemporary Black cinema, too, “carr[ies] a burden of expectation”: from “raunchy comedies” to “feel-good family films” to “the awareness-raising films that tackle major race-related issues, and, […], the work of Tyler Perry,” Black films “hav[e] to be everything to everyone because we have so little to choose from.” (BF, p. 244)

Sexualized Asian Females, Desexualized Asian Males & Yellow Face

How about Asians? Well, Asians were found to be “the least represented minority in the media by a large margin,” as Peter Westacott points out in his TEDx talk “Asian Misrepresentation in Media.” In films or TV shows, the parts Asians get to play are limited, as Westacott’s and David Huynh’s TEDx talks highlight.

Roxane Gay somewhat echoes Westacott’s words in her essay “Girls, Girls, Girls.” Referring to women of color, she writes, “there have been a few shows for black women to recognize themselves – […]. What about other women of color? For Hispanic and Latina women, Indian women, Middle Eastern women, Asian women, their absence in popular culture is even more pronounced.” (BF, p. 60) Indeed, Asian women have to choose within a small range of roles: “the dragon lady or a very sexualized, eroticized Asian femme fatale,” “the tiger mom or a very overbearing, strict mother,” and “the rebellious Asian girl.” As for Asian men, they have to choose between “the kung fu master” and “emasculating, desexualized roles, like the socially inept foreigner or the nerdy math geek.”5 Why, sure, for women you also have the quirky, nerdy character – the antithesis of a femme fatale – and for men you have romantic K-dramas and the rom-coms with Henry Golding. But we can see a distinctive trend in the depiction of (East) Asian characters in the West: a sexualization of Asian women and a desexualization of Asian men.

As an Asian woman, you can become a fetish. There’s abundant literature one can consult on yellow fever and the eroticization of Asian women. Articles worth reading include Renee Tajima’s “Lotus Blossoms Don’t Bleed: Images of Asian Women” which you can find in Making Waves: An Anthology of Writings by and about Asian American Women ed. by Diane Yen-Mei Wong & Asian Women United of California and Audrea Lim’s New York Times opinion piece “The Alt-Right’s Asian Fetish” – to name but two. Alarmingly, the fetishization of the Asian female body begets violence. As Morgan Dewey reports on the website of the National Network to End Domestic Violence, a staggering “41 to 61 percent of Asian women report experiencing physical and/or sexual violence by an intimate partner during their lifetime,” which “is significantly higher than any other ethnic group.”6

If you’re an Asian man in the western society and want to watch romantic leads who look more like you than Hollywood’s golden boys do, you’d better love Always Be my Maybe, The Sun Is Also a Star, Crazy Rich Asians or Last Christmas because that’s about all we have in supply. Films are a powerful vehicle through which we get to see who we are and can become in the world and who others are and can be for us. The lack of Asian men as romantic leads might contribute to what makes it difficult for many women to see Asian men as romantic partners.7

‘Asian Leading Man’ by Alyson Wagner

Yellow fever and its opposite are equally horrific since both involve reducing Asians to dehumanizing stereotypes. Dating someone just because of their race or not dating someone just because of their race ultimately amounts to the same kind of reductive logic.

Sometimes casting directors bypass Asians altogether, even when an Asian person wrote the original story or the story calls for an Asian lead. Whitewashing consists in casting a white actor to play a nonwhite character. “A step beyond that is ‘yellow face’ […] the practice of using makeup and prosthetics to make a non-Asian performer look East Asian”8 or – to use Westacott’s words – of “turn[ing] [Asian] culture and community into a costume.” White actor Mickey Rooney wore make-up and prosthetics to play the Japanese landlord in Breakfast at Tiffany’s. In the same way, in 2017 Hollywood picked Scarlett Johansson to portray the lead character in Ghost in the Shell, using visual effects to make the actress appear more Asian. Are you cringing right now? Me too.

Reality

In actuality, we see or read about stories that are part of a single story feeding our implicit biases.

Why Anti-Asian Racism Is like an Illusionarily Extinct Volcano

In her TEDx talk “I Am Not Your Asian Stereotype,” Canwen Xu shares how, in order to fit in, she separated herself from her Chinese heritage and culture and from the Asian stereotypes. She discusses how society uses Asians as the model minority to have them compete against other marginalized communities, thereby putting Asians in a grey zone.

‘Asian Superwoman’ by Alyson Wagner

“The Dangerous Myth of the Model Minority” is a subject Chanel Miller compellingly tackles in her Instagram post of June 23, 2020. Through simple line drawings, Miller explains how Asians have been subordinate to whites and set against other people of color for generations, and how the inclusion of Asian Americans was conditional. In exchange of specific benefits to white Americans, Asian Americans would be granted opportunity and advancement. Academic excellence, political silence and compliance were Asian Americans’ ticket to assimilation into the selective white American society. The role Asian Americans – and Asian Europeans, I would argue – can serve in society has been that of the highly-educated and -skilled worker – using the singular form seems fitting: Asians have long been considered interchangeable because “they all look the same.”

Because Asians have been stereotypically depicted and seen as better-behaved and smarter than Black people, white folks have had sort of a greater tolerance for Asians – emphasis on the “sort of.” However, this “tolerance” (note the quotation marks) has a flip side: it causes many people to deem anti-Asian racism more socially acceptable because Asians’ plight is not as serious.

Pondering this issue had me look up the word “volcano” in the dictionary – go figure. In the Macmillan, next to the definition per se, a note completes the entry: “Some volcanoes are not immediately dangerous because they are not active and have become dormant. Others will never be dangerous again because they are completely extinct.” Anti-Asian racism is similar to the volcanoes in the first part of that note: it is an on-again, off-again volcano. Although it might appear quiet on the surface, this sneaky volcano is ever-present and erupts from time to time.

An eruption happened amid the early stages of the coronavirus outbreak in France, for instance. Anti-Asian racism reared its head, with passengers chasing French Asians out of public transport or vacating seats next to them. Because China reported the first cases of Covid-19, “Chinese-looking” people became the faces of the coronavirus, which caused many of them to respond with #jenesuispasunvirus (#iamnotavirus) on social media. This is but one example that shows anti-Asian racism is as topical as ever, though it might seem to lie dormant some of the time.

Criminalblackman9

Television is a powerful medium through which we imagine the ways Black people have a chance to succeed. In her essay “Feel Me. See Me. Hear Me. Reach Me,” Roxane Gay argues that the television channel BET, for instance, leads viewers to believe Black people can only succeed through a few specific trajectories, namely “professional sports, music, or marrying/fucking/being a baby mama of someone who is involved with professional sports or music.” (BF, p. 6)

In real life, the prospects are even bleaker for Black people, perhaps especially for young African American men because of the statistics relating to Afro-American male inmates. Not only is racial disparity evident when it comes to the rates of incarceration, but racial inequality and institutional biases further manifest themselves “in the length of sentencing and the effect of incarceration after release.” According to Roxane Gay, “[a]ccurately conceiving of what young black men face when we talk about them as numbers, though, is difficult. […] These statistics, when offered without any kind of reflection, do little to advance the conversation, and when they go unquestioned, […], they distort the conversation.”10 (BF, pp. 247-248)

The impact of how we present those statistics, how we discuss them, and how the news misrepresent Black people, is devastating. The media have taught us to internalize the belief that Black men and violence invariably go together, ingraining these associations in our collective consciousness. This video by Saleem Reshamwala, “Peanut Butter, Jelly and Racism,” explains it clearly and concisely.

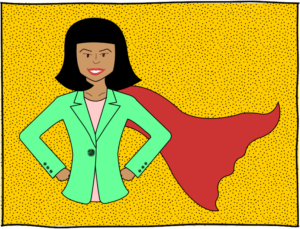

‘Disruptive, Disrespectful and Rude’ Oil on Canvas by Christopher Adam Williams

“When people are shown images of Black men and white men, we are more quickly able to associate […] that white person with a positive word than we are when we are trying to associate positive with a Black face,” as Vernā Myers says in her TEDx talk. Whom we more readily perceive as good or evil or whom we more readily suspect of criminality has far-reaching repercussions indeed. It determines the opportunities we give to, or rather keep from, Black people, and it threatens their very existence: “racial difference is changing people’s possibilities, that’s keeping them from thriving, and sometimes it’s causing them an early death.”11

Trayvon Martin got murdered on February 26, 2012. He was an unarmed teen carrying iced tea and a bag of Skittles, just “walking around being black.” (BF, p. 282) The way the media reported on the Trayvon Martin case stands in stark contrast with the media coverage within the context of the terror attack Dzhokhar Tsarnaev and his brother committed, because of our “cultural notions about who looks dangerous and who does not.” Rolling Stone featured Tsarnaev on the cover of August 1, 2013, and the people who knew him spoke of him in “reverential terms” while, when Martin died, “certain people worked overtime to uncover his failings, even though he was the victim of the crime.” (BF, pp. 286-287) In Gay’s view,

Zimmerman killed Martin because Martin fit our cultural idea of what danger looks like. […] the people who knew Tsarnaev are still willing to see the man behind the monster. […] He committed a monstrous act, but he retains his normalcy. […], Tsarnaev benefits from so much doubt from his friends, his community, and those who seek to understand him […] This, […], is yet another example of white privilege – to retain humanity in the face of inhumanity. For criminals who defy our understanding of danger, the cultural threshold for forgiveness is incredibly low. (BF, pp. 286-287)

In Ryan Coogler’s biographical drama Fruitvale Station, whenever Oscar Grant says goodbye to his girlfriend or to his family, “he adds, ‘I love you.’ Coogler remarked that many young men in the inner city do this because ‘every time we leave the house, we know we might not make it back.’” (BF, p. 249)

Photo by Clay Banks on Unsplash

The long-established association between Blackness and danger affects Black women, too. All too often, Black women are victims of prejudice and violence while going about their daily lives. In her essay “Peculiar Benefits,” Roxane Gay mentions the “infuriating reminders of [her] place in the world”: “random people questioning me in the parking lot at work as if it is unfathomable that I’m a faculty member, […], strangers wanting to touch my hair.” (BF, p. 17) I’ll discuss in greater detail the challenges faced by Black women in particular in “Misogynoir” and “Idealized White Beauty & its Corollary.”

The Exclusion of Black Millennials

The media play a significant role in the perpetuation of racial myths when it comes to subjects other than crime as well, and can influence us in insidious ways. Sometimes it’s what is kept quiet that contributes to distorting our perception of reality. Take millennials. Millennials get a bad press. The media tend to put them in a box, but white upper-middle-class millennials’ experiences differ from Black millennials’. As Tiana Clark writes in her post “This Is What Black Burnout Feels Like,”

we are all so damn tired and in debt, but that pain and exploitation are stratified across various identities, […] discussion about millennials and their ideas of ‘success’ are often deeply rooted in the experiences of privileged White men and women […], being burned out has been the steady state of black people in this country for hundreds of years. […], I clench up and freeze every time I see a cop car driving behind me. […] Burnout for white, upper-middle-class millennials might be taxing mentally, but the consequences of being overworked and underpaid while managing microaggressions toward marginalized groups damages our bodies by the minute with greater intensity.12

“Millennials are not a monolith,” as journalist Reniqua Allen emphasizes in her TED Salon talk “The Story We Tell about Millennials – and Who We Leave Out.” Minimizing Black millennials’ voices and stories or disproportionately leaving them out will do nothing but increase divisions.13 When the media downplay the seriousness of the Black experience, it is Black people who pay the price.

On High Alert

It seems especially in America, systemic racism has forced Black people to develop a sort of hypervigilance and lead lives marked by fear, strength, and survival. In her speech entitled “The Uses of Anger: Women Responding to Anger,” writer and social justice activist Audrey Lorde said “my anger has meant pain to me but it has also meant survival.” And what it takes for Black people to survive in today’s world is nothing short of “hysterical strength,” as Nicole Sealey writes in her poem “Hysterical Strength.”

This video, named after football player & civil rights activist Colin Kaepernick and Stephon Clark who got killed in 2018 in his grandmother’s backyard in Sacramento, features visual artist Christopher Adam Williams, and gives access to a Black man’s internal monologue and gritty determination to survive.

Over the years, many Black people – among whom civil rights activists Rosa Parks and Fannie Lou Hamer – have described themselves as “tired.” This shouldn’t come as a surprise: being constantly on high alert is tiring. It’s been 55 years since Fannie Lou Hamer said “Can we call this a free country, when I am afraid to go to sleep in my own home?” Her words call to mind the unjust shooting of Breonna Taylor in her own apartment earlier this year.

In 1961 a white doctor performs a hysterectomy on Fannie Lou Hamer without her consent. At the time it is common to sterilize Black women to curb the Black population. In 1963 the police arrest Hamer and other Black women for sitting in a bus station reserved for whites, and beat them up, leaving Hamer with severe injuries. A year later, Hamer challenges with admirable bravery Mississippi’s all-white delegation. She seeks to make sure Black people get to exercise their constitutional rights. In the same era, Amelia Isadora Platts Boynton too protests against racial discrimination. She participates in a march later called “Bloody Sunday” because of the inhumane violence exerted on the marchers. Boynton falls unconscious and suffers throat burns because of the police’s reckless use of tear gas. “Me and my people just about due” Nina Simone sings in “Mississippi Goddam” a year before “Bloody Sunday.” And yet here we are, over half a century later.

Countless times Black people have fought for their rights and countless times their voices have been stifled in various ways.

In his riveting TED talk “How to Deconstruct Racism, One Headline at a Time” Baratunde Thurston also uses the word “tired.” No need for Black people to march or challenge the government for them to end up in humiliating situations. White people were found to call on the police to handle drug abuse and homelessness, as Dr Phillip Atiba Goff mentions14 – in other words, issues that don’t require the intervention of armed people – and, as Thurston reveals, they were found to call 911 for just about anything really. Research from the Center for Policing Equity shows that, in some American cities, 911 calls initiate most of the interactions between cops and citizens, and that the police use most of the force on citizens in response to those calls. As Thurston puts it, many white American citizens weaponize their discomfort: “we live in a system in which white people can too easily call on deadly force to ensure their comfort. […] I walk around in fear, because I know that someone seeing me as a threat can become a threat to my life.”

What seems to be needed from white American citizens is heightened awareness about the consequences of such calls and a stronger sense of fairness. Knowing that Black people benefit from far less clemency on the part of police officers, white American citizens have a moral duty to make sure interactions between the police and Black American citizens don’t degenerate into violence, when there is a valid reason for such interactions in the first place.

I live in Europe but, after George Floyd’s death, I saw graffiti on a wall as I was walking through a park. Next to “Justice for George Floyd,” other names were written and the graffiti was also a call for rethinking the role of the police. It was a plea for justice worldwide. I think that, when something shocking and unjust happens, even if it happens on the other side of the globe, it hits home because people of color elsewhere think it might have happened to them.

“I want to live.” Photo taken during a BLM protest in Paris, France, by Thomas de Luze on Unsplash

Looking Beyond the Pigeonholes

There’s no need to go to extremes and distrust popular media. Drawing such a conclusion would be a hasty shortcut. At the same time, we need to be careful consumers and develop media literacy. It’s about balance. We’re lucky to have a world of arts and of communication that keeps us entertained and informed every day, but we need to keep in mind that this world is responsible for portraying people of color in a way that does them justice. The media’s downplaying certain aspects and exacerbating others has serious implications, as discussed. As people of color, Brown people, Indigenous people, multiracial people, we need to know that we have a right to true visibility in films and on television, in novels, magazines and newspapers. Not only do we want to see and read about multidimensional, well-rounded characters we can identify with, but we also want to find truth when we watch images or read articles about ourselves – our generation, our ethnicity.

Race-based generalizations are doubly pernicious: the images misrepresenting who minority identities are or what their culture is hold people of color captive and make it hard for them to navigate their racial identity, and these images make it difficult for white people to have an accurate perception of reality and to see and treat people of color as relatable, complex individuals. Regarded as either objects of fantasy or the embodiment of trouble, people of color struggle to be viewed as human equals. The path to better representation in the media is fraught with roadblocks for we’re holding onto tenacious stereotypes. In “The Politics of Respectability,” Roxane Gay touches on the specific notion we have of what Blackness means and how breaking long-lasting, unwritten rules causes discord:

When a black person behaves in a way that doesn’t fit the dominant cultural ideal of how a black person should be, […] [t]he authenticity of his or her blackness is immediately called into question. We should be black but not too black, neither too ratchet nor too boogie. There are all manner of unspoken rules of how a black person should think and act and behave, […] We say we hate stereotypes but take issue when people deviate from those stereotypes. (BF, p. 257)

Concerning quality programming, as underscored, in the western society Asians and Blacks have to settle for the few options available. Netflix, for example, is doing a good job in terms of inclusion and showing more diversity on screen, but we can’t expect Netflix to be our be-all and end-all. In general, we’re making progress, but there’s a caveat. Nowadays many shows pride themselves on reaching a certain ethnic quota. Yet the diverse cast of a show is not necessarily evidence of fair representation. As Roxane Gay notes in her essay “When Less Is More,” referring to Orange Is the New Black, a show “diverse in the shallowest, most tokenistic ways”: the “diverse characters are planets orbiting Piper’s sun. The women of color don’t have the privilege of inhabiting their own solar systems.” (BF, p. 252) They are, in a way, decorative, as has so often been the case.

Because television has overlooked and misrepresented people of color for so long, pigeonholing them and having fixed ideas about who they should be and how they should behave, watching tv with a critical eye is an act of resistance to oppression somehow. In Black Looks: Race and Representation, bell hooks addresses Black female spectatorship. She suggests Black women’s gaze is oppositional: it is their way of becoming critical spectators and agents.

If we keep aiming for the bare minimum, we all lose. “Colorful,” after all, not only means “full of colors,” it’s also a synonym for “interesting” and “exciting.” Integrating true diversity into our fictional and actual worlds, then, means enriching our lives and sharpening our imagination. Imagination is essential indeed: it’s high time we re-envisioned racial identity. We need to welcome the voices of people of color, welcome their perspectives, and truly see them. To quote a well-known passage from Ralph Waldo Ellison’s Invisible Man,

I am an invisible man. […] I am a man of substance, of flesh and bone, fiber and liquids—and I might even be said to possess a mind. I am invisible, understand, simply because people refuse to see me. Like the bodiless heads you see sometimes in circus sideshows, it is as though I have been surrounded by mirrors of hard, distorting glass. When they approach me they see only my surroundings, themselves, or figments of their imagination—indeed, everything and anything except me.

Who we’ve come to consider invisible have, in fact, multiple facets (and gifts to share and stories to tell). I wish the world gave plenty of opportunities to people of color so they become all they can be instead of versions of what the white supremacist society has wanted them to be.

‘Color Is Life,’ my photo

The mere-exposure effect or familiarity principle posits that we prefer things and people we are familiar with. Studies have shown that the more we see someone, the more we like them. We need the media to show the faces of people of color much more often, to make them familiar.

The intent of really hearing the voices of marginalized communities involves being mindful of the narratives we expose ourselves to and asking ourselves critical-thinking questions. In this narrative, does the depiction of people of color prevent me from seeing them as complex humans I can empathize with? Is the writer or speaker minimizing the experiences of people of color, thereby distorting reality? What are the teller’s background and interests? Is s/he denying or excusing any wrongdoing? Which stories are front page? Which don’t get told at all?

Misogynoir15

After focusing a bit more on the depiction of Black men in the media and the enduring associations between Black men and criminality, I find it necessary to discuss the unique challenges Black women have been handling.

Black women have played active roles in the fight for racial equality, dedicating themselves to various areas and contributing different strengths. I’ve already mentioned a few racial justice advocates, but would like to write a few words about Kimberlé Crenshaw.

At TEDWomen 2016, Crenshaw gave a heart-rending, soul-stirring, forceful speech, “The Urgency of Intersectionality,” about police brutality against Black women. Crenshaw introduced the concept of intersectionality to draw attention to the fact that “many of our social justice problems like racism and sexism are often overlapping, creating multiple levels of social injustice.” The experience of being a Black woman involves the interactions between being Black and being a woman. Not only do Black women suffer race bias, but they also have to overcome another form of exclusion, gender bias, to ensure their safety and well-being. This is important to take into consideration since I don’t think any social justice issue can be properly dealt with in isolation.

Crenshaw urges us to “hold these women up, to sit with them, to bear witness to them, to bring them into the light.”16 Artist Christopher A. Williams’s short film Black Joy does just that. It is Williams’s take on the meaning of Black Joy and a loving, tender ode to the female members of his family.

Idealized White Beauty & its Corollary

Toni Morrison started writing The Bluest Eye not long after the movement Black Is Beautiful in the 1960s. As is the case when a minority’s plea for recognition and fairer treatment grows urgent, society slowly started to catch up. In September 1983 Vanessa Williams became the first Black woman to win the title of Miss America, a prize coveted by many since 1921.

Fast forward to the 21st century. As I drafted this part of the blog post, I recalled numberless instances of fascination with quintessential white beauty. I thought of two girls at my school, an African European and a South-East Asian. We were in gym class when I noticed they were wearing blue contact lenses. I was struck by the intensity of their stare and by the contrast between their natural complexions and the artificial, newly bought eye color they were showing off. Much later, two university friends were praising the hues of each other’s blue eyes as we were taking the escalator one day. It might sound silly but I didn’t just feel plain or inferior: I felt ashamed of my appearance.

Then I remembered the mini rag doll I’d made with my mother as a child – her green button eyes, her crinkled black stocking hair, her mocha pantyhose skin. I was never a doll-crazed type of little girl, but I found her beautiful and valued her above the top-rated dolls precisely because she was different from them. Why couldn’t I be so loving towards myself?

In hindsight, I could determine the reason behind the shame I felt as a university student and many times before and after that time on the escalator. As Martha Nussbaum explains in Upheavals of Thought: The Intelligence of Emotions, “[a]n ideal to which one holds oneself has shame as its permanent possibility.”17 Rationally, I knew blue eyes weren’t prettier than brown eyes and that, say, the authentic emotion one’s eyes express surpasses any external attribute one might pride oneself on. But still, I wasn’t immune to the lure of white supremacy culture’s absolute beauty ideal.

I went on to deconstruct long-established associations with beauty, undertaking a literary analysis for my BA thesis on the assessment of physical beauty as a form of institutionalized racism. I compared Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye and Zadie Smith’s On Beauty that explore our evaluation of beauty in the light of racial matters.

Whereas On Beauty doesn’t seem to blame any institution directly, The Bluest Eye investigates how social institutions (films, consumer goods, children’s books, school, family) influence our judgment and condition children to equate whiteness with physical attractiveness and virtue. Pecola worships Shirley Temple, having no Black icons to look up to. She wishes for blue eyes which she considers the portal to a happier existence. Another difference between the two books is that, in The Bluest Eye, the characters regard Blackness as an inherent evil, which isn’t the case in On Beauty. Yet another difference: in Zadie Smith’s novel, Kiki belongs to an affluent segment of society and is not as lonely as Morrison’s Pecola whose isolation is concrete and physical (Pecola suffers bullying at school and her family puts her outdoors).

Both novels, however, suggest that Blackness implies a sense of inadequacy in a white world, and explore how different degrees of darkness shape a hierarchical Black community, with lighter complexions getting access to a higher social status (esp. in The Bluest Eye: spacious and clean properties are linked to whiteness, as opposed to poor and disordered houses, and the sterile lands of Lorain serve as a metaphor for the death of African culture). This is a theme central to Gwendolyn Brooks’s Maud Martha as well. Brooks’s novella deals with a Black girl’s transition to womanhood and her struggle with self-doubt and finding her place in the world. Maud suffers discrimination from whites as well as from Blacks with lighter skin tones. This also calls to mind Nina Simone’s song “Four Women” about women with different skin tones that encourages Black women to free themselves from societal impositions. This hierarchy within the Black community can lead to intraracism which can be as destructive as interracism.

The Bluest Eye and On Beauty both look into the intergenerational transmission of self-disgust as well. The uprooting of Pecola’s mother, Pauline, mirrors Kiki’s but, while Pauline is abusive towards her daughter and assesses her according to the Eurocentric beauty standards she has internalized, Kiki has tried to take precautionary measures to protect her daughter, Zora, from magazines and television, seeking to provide Zora with a loving, enabling environment.

During my stay in India, I saw commercials promoting skin lightening cosmetics. I’ve heard in Japan they sell make-up for Japanese girls to appear more Caucasian. Why is this important? Well, I think this is of paramount importance: I’m led to believe our white-centric beauty ideal is a global issue as well as a cancerous social invention. This is by no means about vanity and who takes first place on the podium. Our aspiring to a specific set of beauty standards can have disastrous impact on the people who don’t fit with this particular aesthetic, and we pass on the self-hatred we are made to develop to the next generation. As Denise Heinze writes in The Dilemma of “Double-Consciousness, “placing value on a very limited set of physical criteria […] can reduce human beings on sight to objects. Idealized beauty has the power to disenfranchise a child of mother love, to psychically splinter an entire race identity, and to imprison all human beings in static and stagnant relationships.”18

I found it necessary to touch on self-shame. Idealized white beauty can result in people of color turning against themselves and each other out of self-contempt. And, if we don’t believe we are worth standing up for, who will? Thankfully, things have been changing for the better. Still, as you can see, challenging old ways of thinking and implementing significant and lasting change takes time. I’m grateful for the progress we’ve made thus far in terms of embracing different types of beauty, but we need to keep questioning society’s expectations of perfection, and make a point of conveying strong and positive messages, especially to impressionable girls and young women.

The Dilemma over whether to Laugh or Not

Chris Rock’s joke at the Oscars in 2016 caused division amid the audience. Some laughed, while others criticized him for making jokes at the expense of one minority to elevate another. Since then and before that, we’ve all found ourselves in situations where we didn’t know how to respond to a borderline offensive joke. This raises a question relating to humor ethics: is it okay to make a punchline out of a minority group? The short answer would be “no,” according to psychological research on disparagement humor.19

Studies on sexist humor showed that “men higher in hostile sexism – […] – reported greater tolerance of gender harassment in the workplace upon exposure to sexist […] jokes.” Those men also “recommended greater funding cuts to a women’s organization at their university after watching sexist […] comedy skits.” Other researchers even found that they “expressed greater willingness to rape a woman upon exposure to sexist […] humor[!]” Another study revealed “women were more likely to view themselves as objects and worry more about their bodies after viewing sexist humour.”20

You can tell a lot about a person by what makes them laugh. According to Shawn M. Burn Ph.D., people are more inclined to enjoy racist or sexist humor if they already carry prejudices about the marginalized groups.21 If you appreciate the target being denigrated, you won’t take the off-color joke as a joke.22 “Jokes are never neutral. The same joke can be funny or not, but can also be racist or not racist depending on who tells it and to whom,” Gil Greengross Ph.D. explains.23

Being mindful of the jokes we tell isn’t just about avoiding to make a belittling joke in front of the butt of the joke, it’s also about making sure we don’t feed existing biases among prejudiced people. Humor “capitaliz[ing] on group stereotypes” becomes dangerous “when consumed by the uninformed or non-critical,” and prejudiced people are “more likely to interpret disparagement humor with a non-critical mindset,” as Shawn Burn points out in her article “If You Laugh Does It Mean You’re Prejudiced?” For them, “the belief that ‘a disparaging joke is just a joke’ trivializes the mistreatment of historically oppressed social groups – […] – which further contributes to their prejudiced attitude. […], when prejudiced people interpret disparagement humor as ‘just a joke’ intended to make fun of its target and not prejudice itself, it can have serious social consequences as a releaser of prejudice.”24 When prejudiced people get exposed to racist or sexist humor, they tend to feel freer to express existing prejudices or sexist attitudes they would otherwise suppress.

I love this quote by Victor Borge: “Laughter is the shortest distance between two people.” Humor can have a real bonding effect. When we laugh with each other, we create a special connection between us. Yet it’s necessary to distinguish between “‘affiliative humor’—telling jokes and funny stories to entertain others and to help them enjoy social interaction” and “‘aggressive humor’—teasing, put-downs, or ridicule.” Positive uses of humor foster bonding, whilst negative uses of humor prevent it. According to Dr. Thomas Ford, “late-night performers, or professors in front of a class—should use humor responsibly, because […] [d]isparagement humor can affect the ways people think about and respond to the target.”

Shawn Burn supports the idea of having greater empathy as both senders and receivers of humor. If something doesn’t feel right, you are allowed to speak out. If you’ve offended someone, why not apologize instead of calling them “too sensitive”? In Burn’s words in her aforementioned post, “we should be more discerning senders and receivers of humor, expressing our concerns when we feel a line has been crossed and apologizing when informed we have crossed one. […] instead of telling people they shouldn’t be offended we should have some empathy and a conversation instead of getting defensive and minimizing their concerns.”

If you want to hear genuine, hearty laughs, rather than target a common enemy and thereby widen the divide, you’re better off seeking to create a connection with all the people in the room and bring them together.

Spreading Minor Miracles

Is the system we live in ridiculous and messed-up and harmful? That’s putting it mildly. What can we do about it? As is often the case when it comes to social justice issues, the path towards betterment is not without obstacles (after all, we’re trying to repair a society after centuries of systemic oppression, cultural conditioning and institutional barriers) but the solutions are at our disposal.

Confession, the Heartbeat of Anti-Racism

If you’re not being anti-racist, you’re being racist, Ibram X. Kendi explains in a TED conversation. Being anti-racist involves “pushing policies that are leading to justice and equity for all. […] the heartbeat of racism is denial, and really the heartbeat of anti-racism is confession, is the recognition that to grow up in this society is to literally at some point in our lives probably internalize ideas that are racist […] to be anti-racist is to believe that there’s nothing wrong or inferior about Black people or any other racial group.”25 After admitting the racial disparities around us are abnormal, we have to figure out “what policies are behind so many Black people being killed by police” and behind “Latinx people being disproportionately infected with COVID,” and how we can help “replace [those policies] with more antiracist policies.”26

What Kendi says during the aforementioned TED interview about confession being the heartbeat of anti-racism calls to mind Marilyn Nelson’s stunning, moving poem “Minor Miracle.” When I read it, it threw me off balance for a moment. “Minor Miracle” inspired the title of this blog post, and guided the present conclusion.

The first step to moving forward in our fight against racial inequities is to acknowledge our faults, to recognize how in a given situation we were part of the problem, and to make amends. It takes humility to question our own behavior, and it takes courage to apologize. Anger is the default emotion for many people. Self-examination doesn’t feel comfortable because, if we look at what’s hiding behind that anger and hatred, we’ll find pain. In James Baldwin’s words in Notes of a Native Son, “I imagine one of the reasons people cling to their hates so stubbornly is because they sense, once hate is gone, they will be forced to deal with pain.” And yet taking this first step opens up a world of possibilities. In a sense, we can’t dissociate our path to self-realization from our social activism, as I’ll discuss.

Of course, on its own, confession, or one minor miracle, won’t bring about real change. We also need to

- teach children to welcome racial groups other than their own, and better understand how we start internalizing racist ideas early on;

- challenge our biases, improve our ability to put ourselves in someone else’s shoes, become aware of the similarities we share with all human beings, and realize that true freedom cannot be attained until everybody is free;

- acknowledge the existence of a culture of whiteness and its disastrous impact, and then deconstruct that culture of whiteness;

- prioritize actions over feelings;

- contribute to minimizing police encounters with Black citizens;

- recognize that racism is a problem that concerns us all, and acknowledge the urgency of the situation;

- mind our language, and strive for representational justice;

- keep learning, develop our interests, and make good use of our personal strengths

If We Don’t Learn to Hate, We Won’t

The thing is, we’re all tangled up in fear. The oppressed live in fear and the oppressors, too, are scared. In human rights activist Desmond Tutu’s words, “the people who are perpetrators of injury in our land are […] ordinary people who are scared.” Part of the solution, then, lies in figuring out where our fears come from, and in deconstructing the injurious racial assumptions we’ve internalized.

Margaret Mead offered valuable thoughts on the root of racism. Rhoda Metraux gathered her insights in a book titled Margaret Mead: Some Personal Views. According to Mead, in a sense, we learn love and hate at an early age. “It does seem true that hatred of a given person or a category of persons or things must be learned. We have to be taught whom to hate, and if we are not taught to hate people in categories, we won’t.” Regarding small children’s fear of the strange, in her view, this fear can turn into hatred, depending on the attitude of the people around them, hence the prime importance of encouraging children to have many experiences with children of different racial groups:

Children’s initial response to the strange often is one of fear. […] If the screaming, fearful child is comforted, reassured and given a chance to learn to know and trust the stranger, he will have one kind of response — one of trust and expectation of friendship. But if his fear is unassuaged or is reinforced by the attitude of the older children and adults around him, he may come to hate what he has feared. This is why it is so important in a multiracial world and a multiracial society like ours that children have many experiences with individuals of races different from their own. (Mead, 1979, as cited in Popova, 2014)27

It is crucial that the discussions pertaining to early childhood education center on how we can raise children so they become highly empathic individuals, and that parents and adults working with kids teach children to value all racial groups equally.

Photo by Nathan Dumlao on Unsplash

In her TEDx talk “How to Overcome our Biases? Walk Boldly toward Them,” diversity advocate Vernā Myers urges us to have the courage to say something, when we listen to the conversations around the table and witness loved ones make inappropriate remarks, in order to set a good example for the children. As Myers says, “we wonder why these biases don’t die, and move from generation to generation? Because we’re not saying anything. […] we’ve got to be willing to not shelter our children from the ugliness of racism when Black parents don’t have the luxury to do so.”

Also, it can be interesting to go back in time as adults to better understand ourselves and to unlearn fear.

As an aside

I thought I’d share findings that can help us foster emotional understanding between cultures. Prof. Jeanne Tsai’s research shows culture might be shaping our ideal affect, that is, how we want to feel, and our ideal affect influences who we choose to spend time with. She cites Chinese and American children’s books that feature characters who express contentment in different ways and engage in different activities for joy to demonstrate that illustrators, advertisers, and publicists choose images that reflect their cultural values, and people internalize and reinforce these values. Those cultural differences mean that Chinese people perceive warmth and friendliness differently from American people, for instance, and that people from different cultures will make different choices and gravitate towards different personalities. Therefore, in order to understand our gut feelings about certain people, it is important to ask ourselves what cultural ideas and practices relating to emotion we were exposed to as children.28

Walking Boldly towards our Biases

In her forenamed talk, Vernā Myers describes biases as “the stories we make up about people before we know who they actually are.” To truly know the people we’ve been told to avoid and fear, Myers suggests that we expand our social and professional circles, and form authentic relationships with the people we’ve learned to be afraid of. In this way, we can see each person holistically and go against stereotypes, and we get to realize they are us:

move toward young Black men instead of away from them. […] It’s about connection. And you’re not going to get comfortable before you get uncomfortable. […] if someone comes your way, genuinely and authentically, take the invitation. […] Something really powerful and beautiful happens: you start to realize that they are you, that they are part of you, […], and then we cease to be bystanders and we become actors, we become advocates, and we become allies.

Whose Story Are We Missing?

If we let our collective hearts contain all humanity, we’ll become aware not only of the ways we are different but also of the ways we are very much alike. We’ll see ourselves in others.

As Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie explains in her impelling TED talk “The Danger of a Single Story,” we create a single story when we show a community as only one thing over and over again until, in our eyes, the people who form it become that one thing instead of human equals. Power governs how many stories are told, how and when they are told, and who tells them. In Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s words,

Start the story with the arrows of the Native Americans, and not with the arrival of the British, and you have an entirely different story. Start the story with the failure of the African state, and not with the colonial creation of the African state, and you have an entirely different story. […] [Stereotypes] make one story become the only story. […] The consequence of the single story is this: It robs people of dignity. It makes our recognition of our equal humanity difficult. It emphasizes how we are different rather than how we are similar.29

“We believe the one who has power,” as Yaa Gyasi writes in her novel Homegoing. “He is the one who gets to write the story. So when you study history, you must always ask yourself, Whose story am I missing? Whose voice was suppressed so that this voice could come forth? Once you have figured that out, you must find that story too.” It seems many schools teach students to glorify colonizers, while they underdiscuss the colonized – when they do discuss them. School curricula and History books give but an imperfect version – the powerholder’s interpretation – of the complete picture.

Curiosity, then, and a willingness to look deeper into uncomfortable truths can contribute to remedying a biased education system. Sources with greater nuance are available, but we have to seek them out. For instance, a great many of us know Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë, but might not have heard of Jean Rhys’s Wide Sargasso Sea which offers a postcolonial response to the much-loved classic, giving the “madwoman in the attic” a voice. Not only do we need to read about minorities and suppressed voices, but we need to listen to stories from them, and get to know overlooked and under-read writers and creatives and their work.

Becoming the Other

In “The Foreigner’s Home” in The Source of Self-Regard, the late Toni Morrison reflects on how uneasy we are with our own feelings of foreignness and our own unraveling sense of belonging: “To what do we pay greatest allegiance? Family, language group, culture, country, gender? Religion, race? And if none of these matter, are we urbane, cosmopolitan, or simply lonely? […], how do we decide where we belong? What convinces us that we do?”30(Morrison, p. 8)

Morrison also emphasizes that the “[p]ressure that can make us cling or discredit other cultures, other languages; make us rank evil according to the fashion of the day […] can make us deny the foreigner in ourselves and make us resist to the death the commonness of humanity.” (Morrison, p. 12)

In addition to striving to see the world through somebody else’s eyes, embracing the foreigner within, and acknowledging our shared humanity, we ought to regard our fellow humans as individuals. Our “inability to project, to become the ‘other,’ to imagine her or him” and our habit of lumping together people with the same racial background are leading to our demise, for “to continue to see any race of people as one single personality is an ignorance so vast, a perception so blunted, an imagination so bleak that no nuance, no subtlety, no difference among them can penetrate.” (Morrison, p. 43)

The enslaver is, fundamentally, enslaved: “If I spend my life despising you because of your race, or class, or religion, I become your slave. If you spend yours hating me for similar reasons, it is because you are my slave.” (Morrison, p. 72) To become wholly free, therefore, means to free another.

“Any real change implies the breakup of the world as one has always known it, the loss of all that gave one an identity, the end of safety. And at such a moment, unable to see and not daring to imagine what the future will now bring forth, one clings to what one knew, or dreamed that one possessed. Yet, it is only when a man is able, without bitterness or self-pity, to surrender a dream he has long cherished or a privilege he has long possessed that he is set free — he has set himself free — for higher dreams, for greater privileges.” James Baldwin, Nobody Knows My Name: More Notes of a Native Son

Deconstructing Whiteness & Reimagining Identity

The problem lies in the fact that we’ve been socialized in a culture of whiteness from birth. In her TED Salon talk “How We Can Start to Heal the Pain of Racial Division,” Ruby Sales defines this culture of whiteness as “a systemic and organized set of beliefs, values, canonized knowledge and even religion, to maintain a hierarchical, over-and-against power structure based on skin color, against people of color. It is a culture where white people are seen as necessary and friendly insiders, while people of color, especially Black people, are seen as dangerous and threatening outsiders, who pose a clear and present danger to the safety and the efficacy of the culture of whiteness.”31

The culture of whiteness is a social construct we can deconstruct. Sales urges us to “move out of the constructs of whiteness, Brownness and Blackness to become who we are at our fullest.”

Building an anti-racist world is crucial for children who represent a particularly impressionable demographic and need adequate role models, but this is also important for adults since our identity isn’t fixed. We change throughout our lives, and it is a beautiful thing to develop a growth mindset. In “Black Studies: Bringing Back the Person,” June Jordan writes, “Body and soul, Black America reveals the extreme questions of contemporary life, questions of freedom and identity: How can I be who I am?” This question of freedom and identity is relevant not only for other people of color but for white people as well.

How can we become who we are at our fullest? According to Prof. Bryan Stevenson, we need to care in a holistic way, as it were, and make sure our realm of concern encompasses everybody: “we cannot be full, evolved human beings until we care about human rights and basic dignity” and realize that “all of our survival is tied to the survival of everyone. That our visions of technology and design and entertainment and creativity have to be married with visions of humanity, compassion and justice.” Stevenson suggests that creating the right kind of identity is powerful because it can help us get people to do things they thought themselves incapable of doing.32

In the On Being interview “The World Is Our Field of Practice,” Rev. angel Kyodo williams speaks about human wholeness and how, in order to transform our society, we have to transform ourselves as individuals.

Reaching for the Stars – Yes, But

As an antidote to our biases against Black men whom some of us have come to fear because of the enduring associations between Black men and violence, Vernā Myers suggests in her previously-mentioned speech “How to Overcome our Biases?” that we “look at awesome folks who are Black, […] to […] reset [our] automatic associations about who Black men are” and contribute to “mak[ing] a society where young Black men can be seen for all of who they are.” It’s essential that we challenge race-based generalizations and that we look at awesome Black men to realize our biases are unjustified.

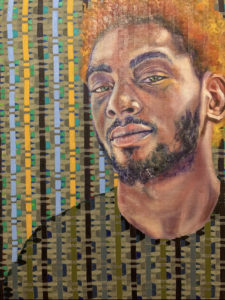

‘King David’ Oil on Canvas by Christopher Adam Williams

Yet that doesn’t mean endorsing respectability politics: we can’t use respectability as a prerequisite for minority groups to earn respect. Marginalized people shouldn’t be expected to be good little soldiers or high achievers in exchange of freedom from discrimination. In her essay “The Politics of Respectability,” Roxane Gay addresses respectability politics – the idea according to which marginalized communities are less likely to suffer racism, if they behave in ways the dominant culture approves of. This idea is problematic as it fails to consider “the ways in which the education system, the social welfare system, and the justice system only reinforce many of the problems the black community faces.” As Gay points out, it is “dangerous to suggest that the targets of oppression are wholly responsible for ending that oppression.” (BF, pp. 258-259)

Also, “[r]acism doesn’t care about respectability, wealth, education, or status”: successful people suffer racism, too. “We must stop pointing to […] these bright shining stars who transcend circumstance. We must look to how we can best support the least among us, not spend all our time […] trying to mimic the greatest without demanding systemic change.” (BF, p. 260)

Actions over Feelings

In her aforesaid talk “How We Can Start to Heal the Pain of Racial Division,” Ruby Sales recounts how one day she “saw both love and hate coming from two very different white men that represented the best and the worst of white America”: a white man tried to kill her and a friend of hers, Jonathan Daniels, took the blast to save her. This is an admirable, heroic gesture of course. No one is asking self-sacrifice of white people though, not even love. Those demanding racial equity are asking for just policies so that such attempts on the lives of people of color don’t happen in the first place.

As discussed in “On High Alert,” calling the police is an action many white American citizens take as a first reaction rather than as a last resort. Baratunde Thurston encourages us to change our actions, thereby changing our collective stories which constitute our systems: “we can change the action, which changes the story, which changes the system that allows those stories to happen. Systems are just collective stories we all buy into. When we change them, we write a better reality for us all to be a part of.”33 For example, for issues relating to homelessness, in his TED talk “How We Can Make Racism a Solvable Problem – and Improve Policing,” Dr Phillip Atiba Goff calls American cities to “deliver social services and city resources to the homeless community before anybody […] call[s] the cops.”

“I do not know many Negroes who are eager to be ‘accepted’ by white people, still less to be loved by them; they, the blacks, simply don’t wish to be beaten over the head by the whites every instant of our brief passage on this planet,” James Baldwin writes in 1962 in “Letter from a Region of My Mind.” In a similar way, Dr Phillip Atiba Goff says in his speech “How We Can Make Racism a Solvable Problem,” “no Black community has ever taken to the streets to demand that white people would love us more. Communities march to stop the killing, because racism is about behaviors, not feelings. And even when civil rights leaders like King and Fannie Lou Hamer used the language of love, the racism they fought, that was segregation and brutality. It’s actions over feelings.”

Likewise, Ibram X. Kendi suggests in the previously-cited discussion “The Difference between Being ‘Not Racist’ and Antiracist” that being anti-racist doesn’t have anything to do with altruism. Rather, it requires “intelligent self-interest”: “Those tens of millions of Americans, white Americans, who have lost their jobs as a result of this pandemic, […] [w]e’re asking them to realize that if we had a different type of government with a different set of priorities, then they would be much better off right now.” Kendi uses the word “love” though. His perspective is, being anti-racist entails a certain kind of love: “at the heart of being anti-racist is love, is loving one’s country, loving one’s humanity, loving one’s relatives and family and friends, and certainly loving oneself.”

I think you can’t have one (actions) without the other (feelings): what prompts us to act and do something about a particular issue is the way we feel about that issue.

It Is about You

I’ve experienced racism – both overt and disguised – many times. It leaves you scarred for life. Still, I don’t know what it’s like to face daily microaggressions, to live with a feeling of constant terror like the Black community in America does. What African Americans have been going through affects me though, and I think that racism in its entirety really concerns us all.

It is more challenging to mobilize anyone who doesn’t think a given issue hits close to home, who doesn’t think it affects them personally. Yet, dear white folks, it is about you. “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere,” Martin Luther King Jr. famously wrote in his letter from Birmingham City Jail. “We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly.”

Some white people have been valuable allies in the fight for racial justice. For example, did you know that Nadine Gordimer counseled Nelson Mandela on his 1964 defense speech and helped him edit “I Am Prepared to Die”? Gordimer was an important contributor to the anti-apartheid movement in South Africa. Only white people could enjoy political rights and power, but as a white woman Gordimer made sure everybody could have the same rights.

In her TEDx talk “Want a More Just World? Be an Unlikely Ally,” equity advocate Nita Mosby Tyler encourages us to build justice where there is none by adding our voices and actions to situations that we might not think are about us.34 In the process, we get to inspire others to follow suit.

Photo by Priscilla Du Preez on Unsplash

The question of privilege puts many of us on the defensive, but acknowledging your privilege(s) doesn’t deny the ways you yourself are marginalized or the ways you have suffered, as Roxane Gay points out in “Peculiar Benefits.” “We tend to believe that accusations of privilege imply we have it easy, which we resent because life is hard for nearly everyone. […] To have privilege in one or more areas does not mean you are wholly privileged.” Gay suggests that we use our privilege “for the greater good” and “try to level the playing field for everyone, to work for social justice, to bring attention to how those without certain privileges are disenfranchised.” (BF, p. 17)

I warmly encourage you to read Peggy McIntosh’s essay “White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack.”

Burning

“Our house is on fire,” Greta Thunberg said, demanding that our leaders take urgent action to combat climate change. The same could be said in reference to the seemingly never-ending fight for racial parity: it cannot wait.

Nina Simone wrote the song “To Be Young, Gifted and Black” in memory of her friend Lorraine Hansberry, author of the play A Raisin in the Sun whose title comes from Langston Hughes’ poem “Harlem” written in 1951. Hughes’ poem calls for long-overdue social change to resolve the injustices the residents of Harlem have been enduring. “What happens to a dream deferred?” the first line asks. In 1963, Martin Luther King Jr. gave his momentous speech “I Have a Dream.” Today racial justice still sounds like a pipe dream at times. The wait feels interminable. No wonder many of us are growing impatient and burning with anger.

There is good reason to remain hopeful though. As Bryan Stevenson says in his TED talk “We Need to Talk about an Injustice,” “the moral arc of the universe is long, but it bends toward justice.” Gwendolyn Brooks, too, calls for progress, trust, and perseverance in her “Speech to the Young”: “Say to them, […], ‘even if you are not ready for day / it cannot always be night.’ You will be right. […] Live not for the-end-of-the-song. / Live in the along.”

Keeping It Up

One day, on my way to work, a fifty-something woman, an old man, and I were waiting to cross the street. Trucks and cars were passing us on both sides and, because of construction work, we had no other choice than to jaywalk. The woman led the way, and the man and I tagged along, three generations crossing the street. You may deem this slice of everyday life trivial or irrelevant, or say this is a classic example that attests to humans’ herd mentality. I like to believe it shows that, when one person sets the pace, s/he sets other people in motion. In the context of social justice activism, when we join forces and show up together, we are stronger, braver, and more effective.

You don’t have to turn into a modern-day Joan of Arc. That’d be amazing, but I know it’s no small thing to ask. We’re probably on this journey for the long haul so, to stay the course, we might as well make it fun. How?

- Keep learning in a way that brings you joy: What stimulates you? What does recreational learning mean to you?

- Develop your interests: What appeals to you? What do you enjoy so much it shakes you awake and makes you lose track of time?

- Contribute your personal skills: How can you live true to yourself and change the world? What is within your capacity to do? What is your medium of communication, of activism?

Kheris Rogers, CEO and designer of the brand “Flexin’ in my Complexion,” launched her own clothing line at 10, flipping off her bullies with style, and inspiring hope and courage in others.

Nnenna Kalu Makanjuola founded Radiant Health Magazine which celebrates Black Women.

Nnedi Okorafor found empowerment in homegrown science-fiction:

Growing up, I didn’t read much science fiction. I couldn’t relate to these stories preoccupied with xenophobia, colonization and seeing aliens as others. And I saw no reflection of anyone who looked like me in those narratives. In the “Binti” novella trilogy, Binti leaves the planet to seek education from extraterrestrials. She goes out as she is, looking the way she looks, carrying her cultures, being who she is. I was inspired to write this story […] because of blood that runs deep, family, cultural conflict and the need to see an African girl leave the planet on her own terms. […] For Africans, homegrown science fiction can be a will to power.35

If you enjoy science-fiction, you may want to get acquainted with Afrofuturistic writing and authors who’ve worked toward making sci-fi more inclusive, like Okorafor, Octavia E. Butler, or N.K. Jemisin.

If you’re an artist, why not combine art and activism, and make socially motivated art? If you’re into photography, for example, you might want to consider using photography to address racism and issues of representation. To name but one phenomenal Black artist who can inspire you to contribute to social change – through her photography, Carrie Mae Weems aims to represent Black women in particular, and to speak to their experience, giving them visibility. Her series “Ain’t Jokin’” addresses racial jokes and internalized racism.

If you have more of an auditory memory and prefer video to text, you might want to listen to Lettie Shumate’s podcast Sincerely, Lettie or watch Emmanuel Acho’s series on YouTube, “Uncomfortable Conversations with a Black Man.” Another podcast worth listening to is Pod Save the People with DeRay McKesson as co-host. McKesson has also written On the Other Side of Freedom: The Case for Hope. From education to ground work, he’s acquired much experience as a civil rights activist.

On social media, I encourage you to follow The Conscious Kid, Check your Privilege and Color of Change. And, if you want to bring change to police departments, join the #8cantwait campaign, a project by Campaign Zero which Brittany Packnett Cunningham co-founded.

Should you want to know more about the model minority myth, I invite you to have a look at Chanel Miller’s Instagram post mentioned in “Why Anti-Asian Racism Is like an Illusionarily Extinct Volcano.” In the caption, Miller gives several reading recommendations worth checking out: the Columbia University publication “The Myth of Asian American Success and Its Education Ramifications” by Ki-Taek Chun, the Washington Post piece “The real secret to Asian American success was not education” by Jeff Guo, The Color of Success: Asian Americans and the Origins of the Model Minority by Ellen Wu, the NBC News article “Officer who stood by as George Floyd died highlights complex Asian American, black relations” by Kimmy Yam, the NPR post “‘Model Minority’ Myth Again Used As A Racial Wedge Between Asians And Blacks” by Kat Chow, the Washington Post article “Young Asians and Latinos push their parents to acknowledge racism amid protests” by Sydney Trent, the book Minor Feelings: An Asian American Reckoning by Korean American poet Cathy Park Hong, and any work by Grace Lee Boggs, a prominent figure in the civil rights movement.

Grace Lee Boggs was married to African American and fellow activist James Boggs. In an interview in 2003, “Revolution as a New Beginning,” she said, “you cannot change any society […], unless you see yourself as belonging to it and responsible for changing it.” In a later interview, she said, “we are the leaders we’ve been looking for.” This reminds me of the last line of June Jordan’s “Poem for South African Women”: “we are the ones we have been waiting for.” You hold more power than you might think.

Regarding what we consume as readers and viewers, as discussed, it is crucial that we improve our media literacy. “See shows with leads of other ethnic backgrounds, with plots that revolve around their lives and experiences,” as David Huynh suggests in his TEDx talk “Asian Enough?”

We need to support the arts in creating a civic and just society for images and narratives shape our understanding of justice. To learn more about representational justice and about the significant and positive impact of the arts, you might want to become familiar with Sarah Elizabeth Lewis’s tremendous work. Syreeta McFadden’s work is also worth diving into.

The list of people bringing to the table knowledge, quick wit, eloquence, and thoughtfulness goes on.

Amplifying melanated voices doesn’t mean brushing aside white voices altogether – A. O. Scott’s New York Times article “Edward P. Jones’s Carefully Quantified Literary World,” for example, is well worth a read, if you enjoy literature. However, it does involve cultivating critical thinking as well as cultural openness.

Finally, bear in mind that language is very important. Striving for racial equality is not only about how we depict people of color or represent them through images, it’s also about the words we use to talk to and about them. “Oppressive language does more than represent violence, it is violence; does more than represent the limits of knowledge, it limits knowledge. […] lethal discourses of exclusion [block] access to cognition for both the excluder and the excluded,” as Toni Morrison explains in her “Nobel Lecture in Literature” in The Source of Self-Regard. (Morrison, pp. 104-105)

In addition to practicing empathy and refraining from using ethnic slurs, one needs to be aware of how language can harm and exclude in subtler ways. For example, a definition of racism can be racist, if it “cares about the intentions of abusers more than the harms to the abused,” as Ibram X. Kendi puts it in his talk on the “Difference between Being ‘Not Racist’ and Antiracist.” What we say matters indeed. A former colleague recounted how he accidentally startled a woman once, when he was traveling abroad. She said to her friend, “that Black scared me!” They were French-speaking tourists like him, so he understood. He told me she could have just said “that man scared me!” This is but one instance of ordinary racism. When such instances don’t remain isolated events but rather become repetitive, I’m afraid people won’t be outraged by them anymore.

We could draw a parallel with the killings of Black bodies. As the number rises and the names accumulate, the problem of police brutality and mass shootings will become an abstract one. To maintain momentum, we need to do more than say the names of the individuals who’ve lost their lives, more than use the right hashtags, more than remove the statues of colonizers, more than rename streets. Otherwise, over time, these actions will become almost mechanic. We need to realize the meaning and significance of the statement “Black lives matter” rather than just chant it. We need to photograph the faces of marginalized communities. Read and listen to as many stories as possible. Get to know people of color up close and personal. Work toward the just society we envision, and remember that white supremacist violence isn’t just about the police actually killing Black citizens. Many people of color die slow deaths.

I walked past the fountain in my neighborhood the other day. The little house wearing lyrics from They Might Be Giants’ “Birdhouse in your Soul” was no longer floating on the water for the reservoir was now waterless. It wasn’t a sad view though: families and children were rollerblading and riding their scooters on the dry reservoir. From afar it looked like they had made an ice staking rink out of it. It reminded me of humans’ resilience and of our capacity for creativity under adverse circumstances: when we lose something, we always find a way to bounce back and build on what is left. We manage to transform a barren land of sorts into a playground.

I’m thinking of the recent elections in America. Trump has left a hell of a mess behind him, but a lot of people have acknowledged the healing can now begin. So, let the healing begin

1. You might want to watch this interview with the founders of Black Lives Matter.↩

2. Paul Rucker, “The Symbols of Systemic Racism – and How to Take Away their Power.” TED. https://www.ted.com/talks/paul_rucker_the_symbols_of_systemic_racism_and_how_to_take_away_their_power (accessed November 30, 2020).↩

3. David R. Williams, “How Racism Makes Us Sick.” TEDMED. https://www.ted.com/talks/david_r_williams_how_racism_makes_us_sick (accessed November 30, 2020).↩

4. Roxane Gay, Bad Feminist: Essays (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2014), p. 209. All references are to this edition. Further cited in the text and abbreviated to BF in the quotations.↩

5. Peter Westacott, “Asian Misrepresentation in Media.” TEDx Talks YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nRvWwrQWsVk (accessed November 30, 2020).↩

6. Morgan Dewey, “Sexualized, Submissive Stereotypes of Asian Women Lead to Staggering Rates of Violence.” National Network to End Domestic Violence. https://nnedv.org/latest_update/stereotypes-asian-women/ (accessed November 30, 2020).↩

7. Ann Lee’s piece on The Guardian “The new heart-throbs” is worth a read.↩

8. David Huynh, “Asian Enough?” TEDx Talks YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wc-Mzf3ztcs (accessed November 30, 2020).↩

9. “Criminalblackman” is a term coined by Katheryn Russell-Brown, author of The Color of Crime.↩

10. That’s not to say some Black men (and women) aren’t offenders, but we must be careful about the labels we assign. Not only do they shape how we see the stigmatized, but they also influence how the stigmatized see themselves. According to the labeling theory, the shaming labels we apply to people cause them to act in a way that corresponds to the labels and to sometimes re-offend. The shamed individuals might think, that’s how they see me anyway, so why bother trying to prove them wrong?